Notes for J. G. Hume Talk

Christopher D. Green

Last revised 21 May 2001

See Proceedings of APA Preliminary meeting (Clark U., July 1892). Who was this "J. G. Hume"?

I. Background/University of Toronto

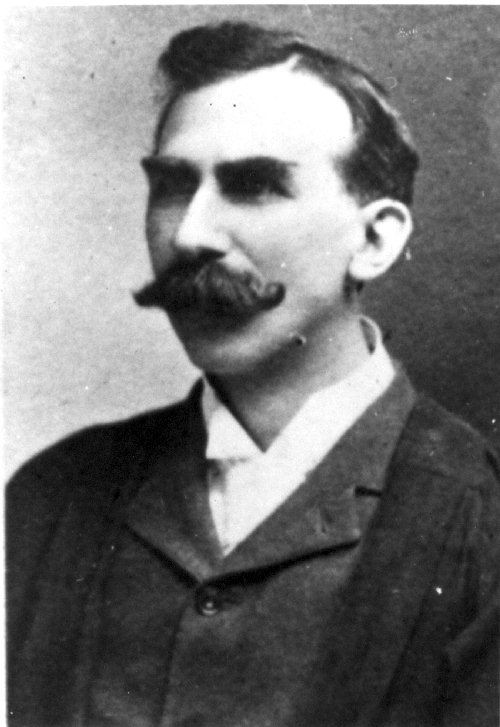

James Gibson Hume, born 1860 in Toronto, raised on a farm near Barrie. Proud of his relation (2nd cousin once removed) to Robert Burns, and dabbled in poetry himself. Joined the "Independent Good Templars" -- a temperance organization -- at the age of 14, and was a life-long prohibitionist. School teacher for a time. Enrolled in St. Catherine's Collegiate Institute (1884?). Transferred to UT in his 2nd year. BA in Philosophy and Classics at UT (1887) under George Paxton Young (UT Prof. Metaphysics & Ethics since 1871). Hume founded the UT Philosophy Club.

Hume went to Johns Hopkins to study exptl. psych. with G. Stanley Hall and H. H. Donaldson, but Hall was headed for Clark the following year and his lab was closing, so he received little or no practical lab training. Hume then went to Harvard -- courses with William James, Josiah Royce. A.M. (1889?).

Class papers for Francis Peabody (Social Gospel Theologian, Prohibitionist) on the "Indian Problem" (Canada's relations with the Indians is better than the US's because Canada has never broken a treaty with the Indians[!] A-), and on Temperance.

George Paxton Young died 20 Feb 1889. John Clark Murray (McGill), John Watson (Queen's) and he were Canada's British Idealist triumvirate. They were suspicious of evolutionism, especially when applied to mental or moral topics, and dismissive of James McCosh's (Pres. Princeton) attempts to harmonize evolutionary theory and Christian doctrine (as well as his Scottish common-sense realism).

Canadian "nativists, esp. James Loudon (UT Prof. Physics) demanded a Canadian, preferably a Torontonian, replacement. Ontario Minister of Education George Ross, himself a nativist, declared no clergyman would be hired.

Daniel Wilson (UT Pres.) favored a candidate more experienced in exptl. psych. than Hume, even if no Canadian could be found. Ontario Premier Oliver Mowat supported Wilson's judgment.

By application deadline of 15 Aug., 22 inquiries and applications were received.

William James wrote letter of reference for Hume, but favored another of his former students, George Howison (at Berkeley), as more experienced.

Principals of Knox (Presbyterian) and Wycliffe (low Anglican) Colleges thought Hume too young for the post, saying that he "would merely give forth a weakened echo of Dr. Young's teachings." Knowing James Mark Baldwin (1861-1934) through Presbyterian connections, they encouraged him to apply.

Baldwin had far superior credentials: PhD Princeton (1887) under McCosh, studied experimental psychology in Berlin and Leipzig for a year. He was teaching at Lake Forest (Presby.) College in Illinois, and had published the first volume of his Handbook of Psych. Letters of reference from G. T. Ladd (Yale) and McCosh, among others.

Wilson supported Baldwin for his knowledge of the "new" psychology. Loudon supported Hume, lobbying the Ontario Cabinet directly. He declared exptl. psych. to be unnecessary, Princeton (viz., McCosh) to be weak in metaphysics, and Toronto's courses to be superior.[!]

Hume later claimed that Young had sent him to Hopkins with the understanding that he would be hired to introduce exptl. psych. to UT upon his return, but there is no supporting evidence. It seems that Hume never received hands-on exptl. training, despite stints with Hall, James, and later Münsterberg.

Popular press became involved in the controversy. The nativist newspaper Toronto World took up the cause of Hume, publishing partisan letters and editorials.

Not until 19 Oct., after the start of the school year, were both offered positions. Baldwin's appointment -- at UT in Logic & Metaphysics -- began immediately. Hume -- Ethics at UC and Hist of Phil at UT -- was given a 2-year fellowship to earn a Ph.D. Baldwin began teaching on 14 Nov. Hume went back to Harvard, and then to Albert-Ludwig University in Freiburg (where Münsterberg taught) for a Ph.D. (1892), but it was not on psychology. His thesis was entitled Political Economy and Ethics. Primary acknowledgement not to Münsterberg, but to one Alois Riehl (described in Münsterberg's biography as the leading philosopher at Freiburg.

Baldwin developed a new course entitled "Psychology" for 1890-91 school year. Fire destroyed UC in Feb. 1890, but Baldwin saw that it was rebuilt with a psych. lab. which was ready for the 1891-92 school year (Science, 19 (475) 1892).

Oct 1891 -- Hume returned to UT. Inaugural Lecture: The Value of the Study of Ethics.

Needing a lab assistant, Baldwin wrote to Wundt to see if Külpe would come. He wouldn't, but Wundt recommended August Kirschmann (1860-1932). Hume interfered, declaring that only a UT grad would do. Ultimately, Kirschmann was offered the position of Lecturer and Lab Demonstrator in 1893. By the time he arrived, however, Baldwin had left for Princeton. He took up all Baldwin's courses on a Lecturer's salary ($800), little more than 1/4 of what Hume made ($3000). (There was talk of replacing Baldwin with Titchener, who had just taken up his post at Cornell, but who wanted to return to "British soil" as he once put it. It came to nothing.)

--------------

II. Membership in the APA

April 18-19, 1892 -- Hume was not a fan of the "new" psychology. He seems to have avoided lab training. In a paper entitled "Physiological Psychology" presented to the Ontario Teachers Association, he was highly critical of its limitations: Science can grasp "change" but not "unity". In psych. it can capture changes in consciousness, but not consciousness itself. Also, its presumption of materialism is incoherent.

July 8, 1892 -- APA Preliminary meeting at Clark. Hume listed as being among 26 "original members who were either present at this meeting or sent letters of approval and accepted membership." We don't know, but the consensus seems to be that it is unlikely, but not impossible, that Hume was actually present. Five additional members were elected, including McGill comparative psychologist T. Wesley Mills, for a total of 31.

Why did Hume join? He may have been among Hall's original invitees, but given his opinion of psychology, why would he be interested? Hall was notorious, however, for telling people what he thought they wanted to hear. Might Hume have been misled? Also, despite the experimentalist polemic of the early APA, several traditional philosophers were active members.

Dec. 27-28, 1892 -- APA First Annual Meeting at U. Penn. It appears that Hume actually attended: 18 of 31 members were present. Those absent are listed; Hume is not among them (though Mills is). 11 new members were elected, including "James [sic -- John] C. Murray" of McGill, for a total of 42.

Oct 1, 1893 Baldwin resigns UT, returns to Princeton.

Dec 1893 -- APA Second Annual Meeting at Columbia. 33 members present, but Hume not among them. (Murray attends, presents "Do We Ever Dream of Tasting?" Mills absent.)

Dec 1894 -- APA Third Annual Meeting at Princeton (co-hosted by Baldwin). A Hume paper on the state of psychology at UT included in program, but it is noted that "This account was presented in the absence of Prof. Hume." Who read it? Baldwin? Why didn't Hume attend? Was there a split with Baldwin? Perhaps, but there was a crisis of sorts brewing at home in Toronto as well.

Dec 1897 -- APA Sixth Annual Meeting at Cornell. "Contributions of psychology to Morality and Religion." Seems to partially retract his earlier opposition to experimental psychology. The psychologist, "should assist the natural scientists in guarding against the misconceptions of materialism. A psychology that takes its stand upon the actual, concrete, active self is the most positive refutation of the abstractions of materialism and pantheism" (p. 163). Thus, it appears that his overall orientation had not changed, but by this time he seemed to believe that experimental psychology could be enlisted in its support.

Remained a member until at least 1903 (after which full membership lists stopped being published with Proceedings).

----------------

III. Teaching

Hume was not popular with students. On 7 November 1894, the UT student newspaper -- the Varsity -- ran an editorial on faculty incompetence. Hume not mentioned specifically, but Philosophy was first among the list of departments described as having "notorious instances." Assoc. Prof. of Latin William Dale publicly supported the Varsity and was fired, leading to a short student strike. Minister of Education George Ross reported, after investigating, that "Mr. Hume is not always clear, though he appears to know his subject." Might this crisis have contributed to Hume's not travelling to Princeton in December to read his paper at the 3rd APA meeting? We do not know.

Ten years later (1904), the Globe ran its own series of pieces on faculty incompetence. Hume was again among the targets. Again it came to nothing.

------------------

IV. Contributions and Publications

Apart from the Ontario Teachers Association piece, Hume rarely wrote on psychology, nor did he ever conduct any empirical research. What he did write, and there wasn't much, was mostly locally published and on ethics and social policy. Frequent public speeches, usually in churches, clubs, or for teachers. He typically adopted a stern moralist stance. Protestantism. English-ism. Temperance. Particularly exercised about standardization of English spelling/pronunciation. Promoted various social causes, usually conservative.

Jan 1, 1894 Ontario Prohibition plebiscite was held (63% in favor), following successful plebiscites in Manitoba (July 1892) and PEI (Dec. 1893). The Tory federal gov't, however was in crisis -- MacDonald died in office June 1891, Abbot resigned Nov. 1892, Thompson died in office Dec. 1894. Bowell's cabinet revolted over the Manitoba schools question in 1896, Tupper lost to Laurier's Liberals later that year. -- and never acted on the plebiscites.

1894 piece in Knox College Monthly on "Socialism" (by which he meant the duty of society to regulate personal life -- prohibition being the main example). Against pragmatism. Against "materialistic naturalism." Against alcohol. For conventional religion. Declared Christianity superior to Stoicism, Epicurianism, Hinduism. Protestantism superior to Catholicism. Assumed a kind of religious "progressivism." English revolution "morally superior" to the French Revolution. Individualism leads to anarchy. Critical of Spencer's social Darwinism. Some admission of the flaws of extreme socialism as well; truisms like: "Gov't is needed, indeed; but it is a necessary evil and the less of it the better for all." Pretty conventional stuff for the day

1897 Introduction to Canadian edition of Joseph Baldwin's Psychology Applied to the Art of Teaching.

Sept. 28 1898 Dominon Prohibition Plebiscite held. It passed handily everywhere but Québec. Canada-wide total was 51% in favor. Because only 44% of eligibles voted, Laurier did not act on the result. Re-elected with increased majority in 1900 (but lost seats in Ontario).

1900-01 "Prohibition as a Problem of Individual and Social Reform," Acta Victoriana (Vic. Coll. serial)

1901 "Introduction" to a volume of translations of Schopenhauer's work.

1907 "Practical Value of Psychology to the Teacher" Ontario Teachers' Association

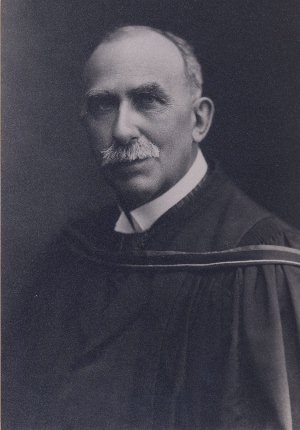

1907 Lecture at Queen's, "Evolution and Personality." Would be virtually his only serious philosophical publication. First half a rejection of (materialist, naturalist) evolutionism in general; Spencer in particular. (One wonders if Baldwin's landmark article "New Factor in Evolution" (1896) was an unmentioned target as well.) Evolution can't be a "natural" law because it implies "moral" progress. Declares his own position to be "Constructive Idealism": derived from Kant (though more directly from British Idealism, esp. T. H. Green), "resolutely opposed to both materialism and rationalism" (an ontology vs. an epistemology?), but doesn't detail the position. Most of this is philosophical "code" for Canadian nationalism, distancing oneself from the American philosophical developments of the new "scientific" philosophers like James, Dewey, Peirce. Second half urges that human "personality" cannot be explained by evolution, but only by constructive idealism. "Personality" conceived as several kinds of consciousness (self-, self-regulative, self-sacrificing, co-operating, etc.). Concludes that "theism" -- Christianity specifically -- explains the facts of consciousness better than materialism or pantheism. Does not really come to terms with the new "scientific" philosophy of the day. UT Philosophy Department historian John Slater describes it as "a tissue of abstract nouns linked together in the most tenuous way" (p. 146). Abstracted in University of Toronto Monthly (1907, 7, 130). Not published in full until 1922, in a Festschrift for John Watson (Queen's).

1908 Giant joint meeting of AYA, AFA, Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology, and the AAAS at Johns Hopkins. Hume gives paper to AFA, a critique of pragmatism, defense of "intellectualism" (British idealism). He is also a discussant on the SSPP Presidential Address (MacBride Sterrett) about the proper relations between psychology, philosophy, and natural science. Hume argued that psychology belongs with philosophy.

1909 9th American Philosophical Association (Yale). Paper on suicide. Called for more detailed statistical tables on suicide; studies of physiological, psychical, literary[!], and social causes of suicide. Closes with a demand that "realistic newspaper accounts of suicide … be checked by legislation"[!]

As WWI approached (Aug. 1914), he became interested in the subject of war and of the "German character," for obvious reasons. Highly partisan. Seemed to wage a war of his own on German philosophy.

One day after the British entry into WWI (in Aug. 1914), Münsterberg published "Fair Play" in the Boston Herald (soon reprinted by fifth papers across the US), an essay defending Germany, and soliciting American support for its position (or at least neutrality). Other pieces followed, reprinted in the volume The War and America (1914)

Nov 1914 Hume gave a lecture in Toronto calling Münsterber's words "vile slanders" and his actions "calamitous and wicked." Also criticized German philosophers, including Wundt, for defending Germany.

Summer 1915 Dropped all German works from his course reading lists.

Dec. 1915 Wrote a front page editorial for the Varsity in which he said, "outside of Kant and Hegel, very little indeed has been contributed by the German mind to the field of ethics." Suggests that German "Kultur" has "nothing philosophical about it": "Machiavellian," "blood and iron," "pseudo-philosopher Nietzsche," "perversion of popular Darwinism," "state-owned railways[!?]". British writers, by contrast, "have carefully and assiduously cultivated this field [ethics] since the time of Hobbes…" (N.B. Wundt published 600+pp. treatise Ethics (1886), trans. by Titichener et al. (1897)

Jan. 1916 Another p. 1 editorial in the Varsity. It opens: "The present war is a conflict between Militarists and Anti-Militarists, between Slavery and Freedom, between Autocracy and Democracy, between Tyranny and Liberty." It closes: "From one end of the British Empire to the other or rather all round the world where Britons dwell, everyone feels the righteousness of Britain's call to her sons to rally in the defence of the Right."

Dec. 1916 Hume published obituary (of sorts) of Münsterberg in the Varsity. "When he came to Harvard he soon showed that he was more interested in German politics than anything else." Closed with account of 300 US professors and prominent citizens who had signed a letter attesting to the "perfidy of the Germans, and their guilt in starting the war."

1916 Commentary in UT Monthly on speech by eminent UT biochemist Archibald Byron Macallum (pub. in Science, 1916) favoring pragmatism over "absolutist" approaches to truth. Hume critical of William James in particular. Interesting comparison: Although Macallum started out very much like Hume (BA Toronto 1880, PhD Johns Hopkins 1888), he was the opposite as an academic. Becoming a UT Prof. in 1891, he was instrumental in the modernization of the UT Medical Faculty, discovered one of the first neurotransmitters, FRS 1906, left UT to become Chair of the Research Council of Canada 1917, taught medicine in Peking 1920, Prof. at McGill 1920-1929, was an outspoken advocate of public educational reform in Ontario.

---------------

V. End of Career

1919 Admin. takes budgetary control of psych. lab away from Philosophy (and Hume), though it remained nominally part of the Philosophy Dept.; Given to psychiatrist Charles K. Clarke. Clarke retired in 1921, lab given to George Sidney Brett, who'd been in the background at UT philosophy since 1908.

Hume forcibly retired in 1926, regarded by admin. as being responsible for poor, backward state of philosophy at UT over previous 30 years. Brett made head of Phil. Dept. Psychology became its own Dept. under Alexander Bott in 1927, who led it until 1956.

Hume became Chairman of newly-formed Canadian Prohibition Bureau after retirement.

Died in Brantford, ON in 1949.

---------------

(My thanks to John Slater, who made the ms. of his history of the UT Phil. Dept. available to me.)