Park, T., Lee, U., MacKenzie, I. S., Moon, M., Hwang, I., & Song, J. (2014). Human factors of speed-based exergame controllers. Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI 2014, pp. 1865-1874. New York: ACM. [PDF] [video]

Human Factors of Speed-based Exergame Controllers

Taiwoo Park1, Uichin Lee2, I. Scott MacKenzie3, Miri Moon4, Inseok Hwang1,5 & Junehwa Song1

1Dept. of Computer ScienceKAIST, Korea

2Dept. of Knowledge Service Engineering

KAIST, Korea

3Dept. of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

York University, ON, Canada

4Div. of Web Science Technology

KAIST, Korea

5Center for Mobile Software Platform

KAIST, Korea

{twpark, miri.moon, inseok, junesong}@nclab.kaist.ac.kr, 2uclee@kaist.edu, 3mack@cse.yorku.ca

ABSTRACT

Exergame controllers are intended to add fun to monotonous exercise. However, studies on exergame controllers mostly focus on designing new controllers and exploring specific application domains without analyzing human factors, such as performance, comfort, and effort. In this paper, we examine the characteristics of a speed-based exergame controller that bear on human factors related to body movement and exercise. Users performed tasks such as changing and maintaining exercise speed for avatar control while their performance was measured. The exergame controller follows Fitts' law, but requires longer movement time than a gamepad and Wiimote. As well, resistance force and target speed affect performance. User experience data confirm that the comfort and mental effort are adequate as practical game controllers. The paper concludes with discussion on applying our findings to practical exergame design.Author Keywords

Exergame; Game Controller; Speed-based Control.ACM Classification Keywords

H.5.2 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: User Interfaces-evaluation/methodology, input devices and strategies

INTRODUCTION

Sports are an entertaining and engaging part of many people's lives, enhancing both athletic performance and physical condition. However, busy urban lifestyles make social sports difficult to participate in since they usually require a pre-determined schedule. Solitary exercises such as stationary cycling or running on a treadmill are popular alternatives; however, the monotonous and repetitive nature of these exercises present challenges to increasing people's motivation to exercise. Moreover, it may be hard to motivate people to exercise using rewards that are not immediately observable, such as better general health [14] and appearance.

Exergames – games involving physical activity – have shown potential to increase the enjoyment of repetitive exercise [24, 29, 39]. They usually involve new technology, such as an exergame controller that adds a gaming interface to exercise equipment. The transformed device serves as a medium to introduce fun factors such as coordinated interactions and competition to repetitive solitary exercises. The device also provides an opportunity for game developers to design interactive exergames similar to commonly enjoyed video games. We envision that new exergame controllers will emerge featuring rich interactivity and immersive game play.

Academia and industry strive to develop new exergames and game controllers. Yet, the design of an exergame is challenging. The reason is simple: Exergames require and promote exercise, unlike traditional video games which primarily seek to entertain. Mueller et al. describe the property of exergames as follows: "The outcome of exergames is predominantly determined by the physical effort" [26]. In contrast, designers of traditional games generally strive to minimize physical effort [33]. It is thus important to correctly understand exergames and to accumulate appropriate design knowledge – to guide designers.

Existing studies, however, are generally limited to exploring how exergame controllers influence the design of in-game content and user interaction. A deeper understanding of controllers will help designers predict, organize, and evaluate exergame experiences. As our research goal, we evaluate an exergame controller to help designers accommodate characteristics and limitations of input devices in exergame design. We study human factors of speed-based exergame controllers (e.g., performance, comfort, effort) under two different types of tasks: a maintenance task (maintaining exercise speed) and a pointing task (moving between points). Also, we examine the user experience with a speed-based controller. The following contributions emerge from our investigation with bike-based exergame controllers:

- The performance of a steady-speed maintenance task is dependent on target speed and

resistance force of an exercise device. Contrary to expectations, performance does not

proportionally degrade as the target speed and resistance force increase. The

performance rather abruptly drops when these values exceed certain thresholds, even

though they fall into the recommended aerobic exercise ranges. This finding implies

that exergame designers should carefully select a proper speed range and consider a

user's preferred resistance level to provide users with a consistent perception of

controllability.

- The results of a pointing task show that speed-based exergame controllers follow

Fitts' law but with a steeper slope than with other devices.

- Our interviews and questionnaire provide detailed reports about user experiences in

using the speed-based controllers. These results help game designers anticipate

players' performance and user experiences.

- We discuss a number of design implications in a case study of a practical game design. We show how exergame designers can consider the findings, such as speed mapping, object placement/control, and difficulty setting.

RELATED WORK

Novel game controllers permit new ways of interacting in exergames. A foot pad in Dance Dance Revolution by Konami [19] allows players to perform rhythmic stepping with music. In Remote Impact [25] and LightSpace by Exergame Fitness Co. [5], players punch or touch a large contact-sensing smart wall. Similarly, in Table Tennis for Three, users hit a virtual object on a smart wall with a ball [27]. Several exergames incorporate physiological sensors (e.g., heart rate) [24, 29, 39]; for instance, remote joggers exchange heart rate information for a balanced running experience.

Motion-based game controllers have recently received a great deal of attention following the release of popular gaming consoles such as Sony EyeToy, Nintendo Wii, and Microsoft Kinect. These devices can detect a player's body motion using cameras and motion sensors. The popularity of these gaming consoles has motivated the design of exergames such as Wii Fit, Wii Sports, and Kinect Sports. Researchers also designed and evaluated specialized exergames in particular contexts, such as rehabilitation [10, 15, 16] and social relationships [40].

Alternatively, exercise machines are widely used as exergame controllers. Exercise bikes are popular due to their familiarity and accessibility [36]. In 1983, Atari Interactive prototyped an exercise bike connected to a game console and devised prototype games such as a racing game. Similarly, AutoDesk developed HighCycle, which allows users to explore a virtual landscape using an exercise bike. Recent products include Cateye GameBike and PCGamerBike, which support the control of a variety of games (mostly racing games) on Sony PlayStation and personal computers. Fisher Price's Smart Cycle offers educational exergames for young children, with a control mechanism similar to the games shown in Figure 1a and 1d. Park et al. [31] recently demonstrated the potential of existing exercise devices as exergame controllers for repetitive body movements (e.g., treadmill running, cycling, rowing, rope jumping).

Figure 1. Games which can be controlled by speed-based controllers: (a) shooter, (b) paddle game, (c) puzzle game, (d) action game. Players can relocate the avatar's position using (e) a stationary cycle or (f) a traditional controller.

A large body of work focuses on developing new exergame controllers (e.g., smart wall) [5, 25] or evaluating well-known motion-based controllers such as Wiimote [28]. To our knowledge, a comprehensive study on fitness equipment-based controllers has yet to be reported. This study aims to bridge this gap and deliver practical game design implications. Our work complements other exergames studies on context (e.g., education [1], medical [12, 40]) and benefits (e.g., exercise effectiveness and adherence [41], social relationships [40], and cognitive function [9]).

SPEED-BASED EXERGAME CONTROLLERS

This work focuses on fitness equipment with repetitive physical movements, such as treadmills, indoor cycles/rowers, and elliptical trainers. Speed-based exergame controllers require continuous physical effort, a major departure from existing devices for games, such as a mouse or gamepad. The intensity of exercise (i.e., linear/angular speed) is used to realize one-dimensional speed-based movement control. On a stationary cycle, for instance, the angular speed (or pedaling speed) is mapped to the speed of an avatar. Speed is altered by pedaling faster or slower (Figure 1e). Such speed-based movement control differs from existing distance-based movement control in traditional pointing devices (e.g., mouse, Wiimote) where linear movement of the device is directly mapped to an avatar's movement.

As such, using speed-based exergame controllers requires a fresh look at the characteristics of game play. We compare and discuss the characteristics of traditional and speed-based controllers. For simplicity, we focus on two major aspects of control: maintaining the current state and transitioning to a different state.

For a maintaining activity, the player's goal is to keep the current game state. Examples include holding an avatar's position in a scrolling game or maintaining the current speed and direction in a racing game.

For a transitioning activity, the player's goal is to change the game state, such as relocating an avatar to a different position or steering a vehicle to a new path. Typical traditional controller designs, such as buttons or joysticks, are effective in identifying the player's intent for either maintenance or transition. Examples include pushing a button (transition) or not (maintenance), or tilting a joystick (transition) or holding it at a fixed position (maintenance). Figure 1f illustrates the process of relocating an avatar along the vertical axis and holding its position by a traditional controller.

In contrast, the original design goals of speed-based controllers do not consider whether the player's intention is maintenance or transition. Instead, the goal is the precise and continuous measurement of the parameters representing a player's instantaneous exercising intensity. A common practice in designing speed-based exergames is to leverage the value of a speed-equivalent parameter as a 1-dimensional controller input, and translate it into a unique game state. An example is revolutions per minute (rpm) for a stationary cycle [38, 39]. Figure 1e illustrates an example of translating cycling rpm into the avatar's vertical position.

In the cases above, the controller requires the player to maintain physical exertion throughout game play. Even if the intention is maintenance, the player should continue pedaling at a consistent rpm. This characteristic is different from discrete inputs such as pressing buttons. Figure 2a depicts a time sequence of a player's intent while playing games from Figure 1: holding the avatar at position A, moving upward to position B, then holding at that position. Figure 2b and Figure 2c show the player's behavior history and the avatar's actual trace in the game when using a game pad and a stationary cycle, respectively.

Figure 2. Control mechanism of traditional and speed-based controllers.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The observations above have various implications regarding game play by a speed-based controller. To attain an in-depth understanding and derive unique design considerations of speed-based controllers, we formulate the following research questions.

RQ1. How precisely can players maintain the speed of speed-based controllers?RQ2. Are there specific factors that account for performance during speed maintenance?

As shown in Figure 2c, a certain amount of error persists even when a player's goal is to maintain a specified speed. Here, a number of factors are at work, such as the limited precision of human motor output, the exercise intensity, and the mechanics of the exercise equipment. It was reported that even if a player intends to pedal at a constant rpm, the instantaneous torque is not consistent but increases while the pedals are being pushed, and vice versa [3]. In-depth understanding of the error characteristics and the achievable precision is important in exergame design (e.g., setting the tolerance level to classify the player's input as maintenance). However, this was not seriously investigated thus far in the context of game controllers.

RQ3. What are the differences and similarities for performance and comfort between speed-based controllers and traditional controllers?

Understanding the human factors of a new controller, such as performance and comfort, would assist in designing in-game challenges and in estimating the associated experiences [34]. Manipulating a speed-based controller requires a large displacement of limbs. This may decrease the performance of controlling tasks in terms of accuracy and agility compared to pressing buttons a few millimeters deep. Similarly, requiring the motion of massive body parts could quickly exhaust the users. This might have an adverse effect on user-perceived comfort. To evaluate the performance and comfort of a speed-based controller, we adopt a Fitts' law paradigm [6] to assess performance. This test is widely used in analyzing inter-device differences [4, 21, 22], as well as in predicting user performance while manipulating devices [37]. We measure performance and comfort levels and compare with traditional controllers including a gamepad and a Wiimote.

While examining characteristics of speed-based controllers, we also focus on learning effects, considering inexperienced game players with speed-based controllers. The results will be helpful for game designers to accommodate newcomers, for example, in providing a tutorial or incremental challenges [8, 33].

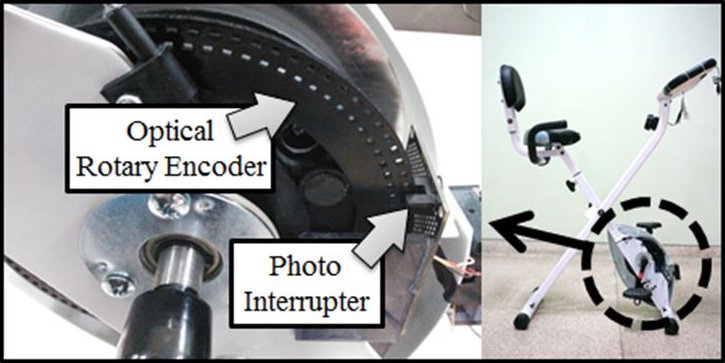

Device Prototype

We built a prototype of a speed-based controller using an exercise bike. See Figure 3. Our prototype monitors angular rotation speed using an optical rotary encoder and a photo interrupter (as suggested by [12, 30]). To smooth unwanted fluctuations in the detected signals, the sensor output is averaged over a sliding interval of 0.5 seconds. This provides a good sense of responsiveness combined with a sufficient resolution.

Figure 3. Hardware of the speed-based controller prototype.

STUDY 1: MAINTENANCE PERFORMANCE

Method

Our first experiment evaluates players' performance for speed maintenance; that is, holding a target speed. As stated earlier, speed-based controllers require players to maintain their speed to retain an in-game state. Considering the operation of exercise equipment, we focus on two factors that may affect maintenance performance: target speed and resistance force of an exercise bike.

Participants

Fifteen participants (6 females) were recruited on campus from an age group of 18 to 23. The average age was 20.8 (SD = 1.82). We advertised that the experiments may require physical abilities related to the operation of an exercise bike. Participants were compensated the equivalent of $10 US.

Apparatus (Hardware)

Input was via the exercise bike, which supports variable resistance in eight levels. Prior to the experiment, we carefully measured the resistance force of the bike (by referring to [23]) and found that the force ranges from 4.89 kp to 35.32 kp, under a 0.5 meter flywheel circumference.1 Output was presented on a 24-inch display with a resolution of 1280 by 720 pixels.

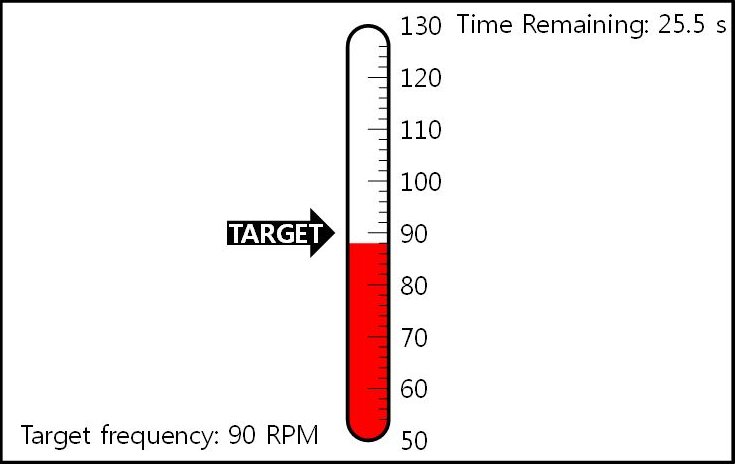

Apparatus (Software)

The test software was developed in Microsoft XNA, a popular game development framework. The display included a vertical speed gauge showing the current speed and target speed as well as the time remaining. See Figure 4. The gauge range was from 50 to 130 rpm with each 10 rpm mapped to 90 pixels (3.75 cm). This range encompasses common pedaling rates in cycle training [2]. The target speed is indicated by an arrow on the left of the gauge. The remaining time appears at the top-right corner.

Figure 4. Screenshot of the maintenance test.

Procedure

Participants performed trials of a simple maintenance task. They were instructed to manipulate the bike to maintain the gauge level as close as possible to the target speed for 30 seconds. A beep sounded at the end of each trial.

Design

A 3 × 3 within-subjects design was used. Independent variables were target speed (f = 60, 90, and 120 rpm) and resistance force (r = 9.2, 14.3, and 19.4 kp, set by resistance levels 2, 5, and 8, respectively). All nine conditions were used and presented in random order until all trials were completed. The dependent variables were offset error and root mean square (RMS) error, both with units rpm. These errors capture the variation between participants' speed and the target speed. In detail, the offset error is calculated for each subject by averaging the differences of all sampled speeds (for the 30 seconds) from the target speed. Similarly, we obtained the RMS error by calculating the root of the squared mean of the differences.

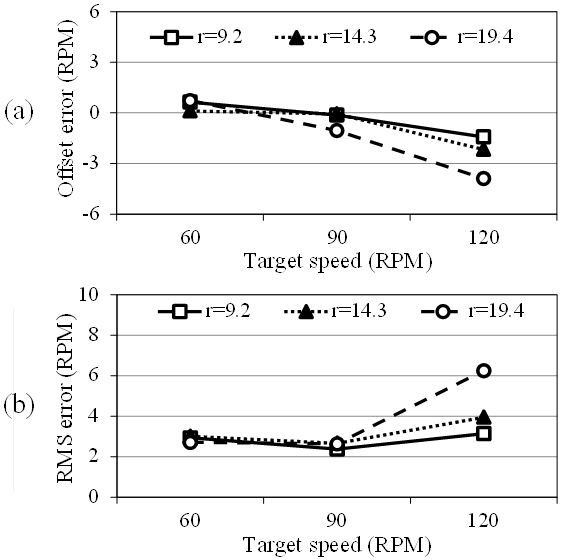

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results for offset error and RMS error are shown in Figure 5. For offset error, the difference was statistically significant for target speed (F2,117 = 20.16, p < .001). For RMS error, the differences were statistically significant, both for target speed (F2,117 = 22.04, p < .001) and for resistance force (F2,117 = 6.09, p < .005).

Figure 5. Error by target speed and resistance force. (a) offset error, (b) RMS error. (Note: the reported values are the means of the measures across all 15 participants. r is the resistance force of the exercise bike in kp.)

Note that the errors do not proportionally increase as the target speed increases. The error rate abruptly jumps when the target speed exceeds a certain value. The offset error is close to zero at 60 and 90 rpm, but is negative and relatively far from zero at 120 rpm, as shown in Figure 5a. The error is more prominent as the resistance force becomes higher. This indicates that with the highest workout combination (120 rpm at 19.4 kp) it was difficult for the participants to maintain the target speed. That is, if a player riding at 19.4 kp of resistance wants to use a range from 60 to 120 rpm, she may feel that controllability is not consistent throughout the range. Under the lowest resistance force (9.2 kp), a paired t-test indicated no statistically significant difference in the RMS error and the offset error.

We investigated the literature on exercise physiology to identify the major factors responsible for errors at higher target speed. The literature indicates that pedaling torque is not consistent throughout a revolution, thereby causing variability on pedaling speed [3, 35]. The causal relationship between the torque and speed could be significant when the resistance level is high [35]. We also found that the inertial load of the cycle crank and flywheel could affect the perceived difficulty in maintaining a target speed [13], and it is thus necessary to take into account these factors.

Thus, exergame designers should carefully select a speed range for game play in consideration of resistance force of the bike, to give users the perception of controllability over the range. We thus set the resistance force as 9.2 kp for the next experiment to facilitate maintenance performance. We also set the minimum target width of the pointing task to require a range larger than 8 rpm, based on the observation that the RMS error was lower than 4 rpm at this level of force.

STUDY 2: POINTING PERFORMANCE AND COMFORT

Method

We designed the second experiment to compare a speed-based controller with popular game controllers, namely, a gamepad and a Wiimote. We anticipated that a speed-based controller may increase the difficulty of control or lead to inconsistent performance. We adapted Natapov and MacKenzie's approach of testing a game controller with a pointing task and checking whether it follows Fitts' law [6], as with other non-keyboard input devices [21, 28]. Here, Fitts' law gives the time to move to a target (MT) as a function of the distance to the target (A) and the width (W) of the target [4]:

MT = a + b log2(A / W + 1), (1)

where a and b are constant coefficients determined through linear regression. The logarithmic term is the index of difficulty (ID, in bits). We expected that the overall movement time of speed-based controllers would be longer than that of traditional game controllers.

Participants

The fifteen participants who took part in the first experiment participated in the second experiment a few days later. They were compensated the equivalent of $50 US.

Apparatus (Hardware)

The input devices included the exercise bike, an XBOX360 gamepad, and a Wiimote. See Figure 6. For clicking with the bike, we attached two push buttons on the handle bar and asked participants to push the buttons using their left or right index finger. To utilize the Wiimote's pointing feature based on infrared sensors, we attached a Wii Infrared Sensor Bar on top of the monitor. The output was presented on a 24-inch display. The distance between the display and eyes of a participant was fixed at 85 cm, with the height of the eyes fixed at the center of the display. The height of the display was adjusted, as necessary, for each participant.

Figure 6. Game controllers used for the pointing task – exercise bike, gamepad, Wiimote.

Apparatus (Software)

The display showed a crosshair-type cursor, centered horizontally. See Figure 7. For the exercise bike, the vertical position of the cursor was directly mapped to the speed of the exercise bike; that is, 50 rpm at the bottom and 130 rpm at the top; with 10 rpm increments mapped into 90 pixels (3.75 cm).

Figure 7. Screenshot of the pointing task. A participant is performing a trial, having just clicked the home square and moving toward the target square.

For the gamepad, participants used the analog stick at the top-left corner. We used only the vertical component of the analog stick data. The analog stick can generate a continuous value from – 1.0 to +1.0 via Microsoft XNA Input Device API, which is mapped to the tilted angle of the stick. We then mapped the value to incrementally change the vertical position of the crosshair on the screen. The maximum velocity of the cursor was ±900 pixels/s when the stick was fully extended.

For the Wiimote, we utilized GlovePIE (v0.36) software and a specialized script to convert the Wiimote data to mouse data. We then mapped the vertical position of the data to the vertical position of the cursor. For clicking, we used the customized push buttons for the exercise bike: 'A' button for the gamepad and both 'A' and 'B' buttons for Wiimote.

Task

A vertical version of a one-directional pointing task was implemented (by referring to [4, 17, 18]) using Microsoft XNA. See Figure 7. A trial starts when a participant clicks on the green home square, and ends when the participant clicks on the red target square. The time between these clicks is recorded as the movement time for a trial (MT in seconds). Combinations of width and distance were presented randomly. (The detailed settings of the combinations follow in the next subsection.)

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups (5 per group). Each participant was tested with all three devices (one device per day, three days in total). The order of testing was counterbalanced using a Latin square. The total time for each participant ranged from 30 to 90 minutes per day for three days. Before testing, the task was explained and demonstrated to participants. Participants were instructed to perform the task as quickly as possible while trying to avoid mistakes. They performed ten blocks of multiple combinations of target width and distance. The participants took 5-minute breaks between blocks to avoid fatigue.

Design

A within-subjects design was used with the following independent variables and levels:

- Input Device {Wiimote, Gamepad, Exercise Bike}

- Target Width {80 pixels, 120 pixels}

- Target Distance {200 pixels, 300 pixels, 400 pixels}

- Block {1 to 10}

- Trial {1 to 10}

Considering the maintenance performance of the exercise bike (within a range of target speeds ±4 rpm), we set the minimum width at 80 pixels, which represents about 9 rpm. This is large enough to contain the maintenance variability. The widths and distances yield Fitts' index of difficulty values from 1.42 to 2.58 bits. A block consisted of 60 trials (10 trials for each width-distance combination × 6 combinations). The trials were presented in random order. A total of 600 trials were run (6 combinations × 10 trials × 10 blocks) for each participant, and thereby the total number of trials was 600 × 15 = 9,000.

Dependent variables were movement time (MT) for each trial and throughput (TP). Throughput is the rate of information transfer measured in bits per second (bps) [17, 18]. We also conducted an exit interview and administered a questionnaire to solicit participants' qualitative impressions and experiences with the test conditions.

Results and Discussion

Learning Effects and Movement Time

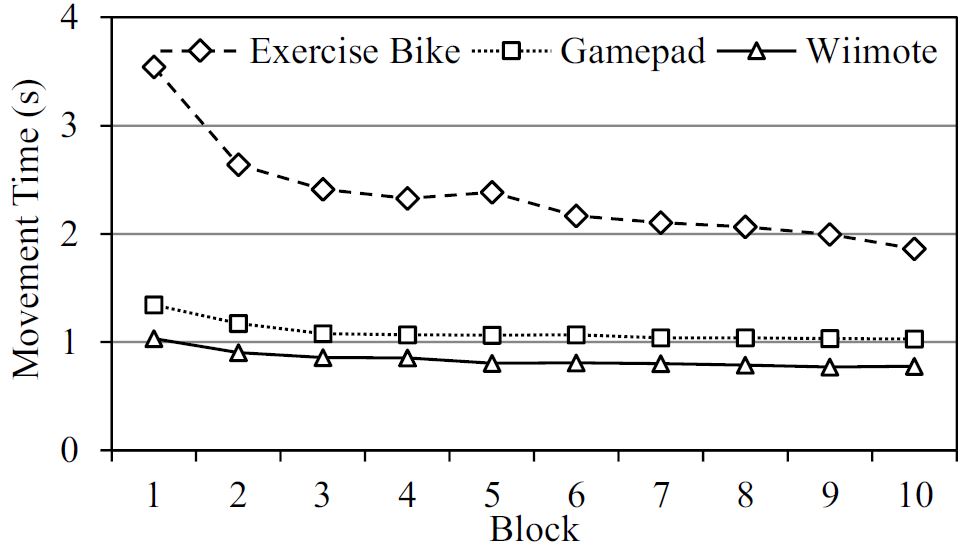

As mentioned above, the speed-based controller offers a manipulation mechanism unfamiliar to many game players. Thus, a learning effect was expected. Figure 8 shows the results for movement time by input device and block. The Wiimote was the fastest device, the bike the slowest. The main effects were statistically significant for input device (F2,420 = 533.27, p < .001) and block (F9,420 = 11.48, p < .001). The input device by block interaction was also statistically significant (F18,420 = 4.19, p < .001).

Figure 8. Movement time by input device and block.

We analyzed Helmert contrasts by following a previously reported approach [22]. The results showed that the block effect was not significant after blocks three and four for the gamepad and Wiimote, respectively. However, the speed-based controller showed significant differences as the number of blocks increases. The movement time of the speed-based controller improved substantially – from an initial value of 3.54 s to a final value of 1.86 s. Thus, there was clearly a much greater improvement for the speed-based controller than with the other two input devices.

It is worth noting the details of the block effect for the speed-based game controller. There were significant differences for movement time from blocks 1 to 6, but no significant differences from blocks 6 to 9. Finally, block 10 showed statistical difference from the former four blocks. Further studies on the learning effect will help identify whether the performance change in the last block occurred by chance. Subsequent analyses were based on means from the last block only because including blocks 6 to 9 did not yield significant changes.

Fitts' Law Models and Throughput

To test whether the exercise bike follows Fitts' law, we separately examined the six combinations of target widths and distances and the five distinct values of index of difficulties (IDs). This is shown in Table 1. For each combination, we computed the error rate (ER) and movement time (MT). Each dependent measure is based on 120 observations (12 participants × 10 trials per combination).

Table 1. Throughput calculations from the Fitts' law experiment.

Distance

(pixels)Width

(pixels)ID

(bits)Exercise Bike Gamepad Wiimote ER (%) MT (ms) ER (%) MT (ms) ER (%) MT (ms) 200 80 1.81 17.33% 1697 3.33% 1032 5.33% 729 200 120 1.42 6.00% 1302 1.33% 873 4.00% 655 300 80 2.25 11.33% 1959 3.33% 1130 6.00% 844 300 120 1.81 1.33% 1662 2.00% 925 2.67% 723 400 80 2.58 12.67% 2413 6.67% 1193 8.00% 915 400 120 2.12 5.33% 2150 2.00% 1032 0.67% 788 Mean: 2.00 9.00% 1864 3.11% 1031 4.44% 776 Throughput: 1.07 bps 1.94 bps 2.57 bps

Figure 9 shows scatter plots and regression lines for the six MT-ID points for each input device. The prediction equations for MT as a function of ID are also shown. R squared values are high for all three input devices, including the exercise bike. The throughput (calculated by referring to [4]) was 1.07 bps for the exercise bike, 1.94 bps for the Gamepad, and 2.57 bps for the Wiimote. Note that our results for the Gamepad and Wiimote are comparable with previous results [28] of 1.48 bps and 2.59 bps, respectively.

Exit Interview and Questionnaire

The questionnaire was a modified version of the Device Assessment questionnaire [4]. There were 18 items on a wide range of human factors relating to effort, fatigue, and comfort. Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale. We used the questionnaire to guide the exit interviews while soliciting detailed explanations related to the participants' responses.

The means and standard deviations of the responses are presented in Table 2. A Freidman test revealed statistically significant differences with respect to the following attributes: force required for actuation (H2 = 16.68, p < .001), smoothness (H2 = 11.88, p < .01), physical effort (H2 = 17.38, p < .001), difficulty of accurate pointing (H2 = 10.65, p < .01), operation speed (H2 = 14.17, p < .001), and overall usability (H2 = 14.63, p < .001). The differences favored the gamepad on the physical effort, accurate pointing, and overall usability, and the Wiimote on the smoothness and operation speed. On the force required for actuation, the gamepad and Wiimote received the poorest ratings. No significant differences were found on the other questions regarding mental effort, operation speed, and general comfort. We did not find any statistically significant differences on comfort and mental workload, although it was noted that the speed-based controller was regarded as slightly less comfortable and required a greater mental workload than the Wiimote and the gamepad (in terms of average values). Overall, the reported levels of comfort and mental effort are adequate with respect to practical use as game controllers (comfort: mean = 3.07, SD = 1.03; mental effort: mean = 3.07, SD 1.39). The participants generally agreed that they could confidently maneuver the device after training. As expected, the required physical effort of an exercise bike is significantly higher (mean = 3.93, SD = 1.33) than existing devices (gamepad: mean = 1.60, SD = 0.63). Smoothness during operation is above the moderate level (mean = 3.13, SD = 0.83), which is slightly worse than that of existing devices (gamepad: mean = 4.27, SD = 0.70). Fast movements are easy to perform (mean = 2.40, SD = 0.63), but accurate pointing was reported to be somewhat difficult, mainly due to the moderate level of perceived smoothness. Overall, the participants believed that when compared with traditional controllers, the exercise bike has a moderate level of usability (mean = 2.93, SD = 1.03).

Table 2. Results of the Device Assessment Questionnaire. Shaded cells show the most favourable response (where statistical significance was attained).

Question Exercise

BikeGamepad Wiimote 1 Force

(1:low – 5:high)*** 3.27(1.28) 1.47(.64) 1.47(.52) 2 Smoothness

(1:rough – 5:smooth)** 3.13(.83) 4.27(.70) 4.33(.98) 3 Mental effort

(1:low – 5:high)ns 3.07(1.39) 2.27(1.33) 2.13(1.36) 4 Physical effort *** 3.93(1.33) 1.60(.63) 1.87(.64) 5 Accurate pointing

(1:easy – 5:difficult)** 3.93(1.22) 2.33(1.11) 2.53(1.13) 6 Operation speed

(1:fast – 5:slow)*** 2.40(.63) 2.33(.90) 1.40(.83) 7 Finger fatigue

(1:none – 5:high)ns 2.20(1.21) 2.80(1.21) 2.20(1.21) 8 Wrist fatigue ns 2.67(1.50) 2.13(1.06) 3.40(1.40) 9 Arm fatigue ns 2.40(1.40) 1.80(1.08) 2.73(1.10) 10 Shoulder fatigue ns 2.07(.88) 1.47(.92) 2.27(.88) 11 Neck fatigue ns 1.93(.70) 1.67(.72) 1.67(.90) 12 Foot fatigue N/A 3.20(1.08) N/A N/A 13 Ankle fatigue N/A 3.67(1.29) N/A N/A 14 Leg fatigue N/A 3.53(1.30) N/A N/A 15 Knee fatigue N/A 3.33(1.18) N/A N/A 16 Thigh fatigue N/A 3.73(1.49) N/A N/A 17 General comfort

(1:uncomfortable)ns 3.07(1.03) 3.67(1.05) 3.80(1.08) 18 Overall usability

(1:difficult – 5:easy)*** 2.93(1.03) 4.33(.82) 4.07(1.10) ***: p < .001, **: p < .01, ns: not significant

In the following, we report user comments from the interviews. Consistent with the questionnaire results, many participants noted that the exercise bike required more physical effort to maintain speed than the gamepad or the Wiimote. One participant reported that it even required more mental workload, commenting, "It was a bit hard to maintain a steady speed [with the cycle] and I had to pay significant attention." Maintaining steady speed requires careful coordination of one's bodily movements. One participant said, "When I feel acceleration, I take some rest [to decelerate]. Then it significantly drops. It's a bit hard to control." Another participant complained that the controller has less control power: "As it may be using body parts, the problem is not that I made any subtle mistakes but that acceleration control is hard to perform." In addition, several participants commented on unfamiliarity: "At the beginning it was really hard to point at the target. And it was difficult to figure out how to control the speed of the cycle." These comments highlight the importance of training and tutorial sessions to help users become accustomed to the controller.

The participants felt that approaching the target area is easy, but accurate pointing takes time and effort. One participant said, "It's difficult to enter the rectangular area as the cursor keeps moving up and down. It is a bit hard to exactly point at the area." The fluctuation in speed comes from a series of repeated acceleration and deceleration activities as the user aims to reach the target speed range. Participants generally agreed that when compared with the gamepad and Wiimote, fine-grained movement control using the speed-based controller is more difficult, as one participant reported, "When I operate the controller, I have to make one small movement after another, and such fine-grained control was a bit hard to make."

In addition, participants commented about asymmetries in physical efforts when making transitions between speed levels: "There was no notable discomfort. It was easy to go down, but it was difficult to go up [during a pointing task]. It does not require a great effort, but it requires quite a lot of attention."

The importance of resistance level was pointed out by one of the participants who said, "The resistance level was good [during the experiments]. But if the level is higher than the current level, there will be a smaller degree of freedom for acceleration, and it will be difficult to perform the task." These comments are consistent with our experimental results, and these aspects should be carefully reflected in the game design.

We collected several comments from the participants that the controllability could be influenced by individual fitness levels, particularly in terms of muscular endurance. One participant commented: "In the final trial, I felt my legs a little bit tired, and I saw the cursor was sometimes not exactly moving as I intended." Another participant said: "I think I could do better if I had better endurance for the entire session." We anticipate that further studies with subjects of different fitness levels would reveal how individual muscular endurance or strength levels would result in a degradation of controllability as trials progress.

EXERPLANET: A DESIGN CASE STUDY

To illustrate how our findings are applicable to practical exergame design, we designed a game called ExerPlanet. It belongs to the shooter game category. Action is viewed side-on, with the screen continuously scrolling horizontally. Other possibilities include action and puzzle games.

Game Description

As shown in Figure 10a, the player's spacecraft moves vertically while planets attack from a horizontal direction. (Note that vertical steering is commonly used in exergame design [7, 11, 36].) The spacecraft continually shoots missiles with the player raining fire on a planet until it is destroyed; a larger planet takes more time to destroy. Points are gained based on the size of the planet. The player seeks to avert a plane crash and to earn as many points as possible to improve their ranking on the leader board.

Detailed Examples: Level Design

The key factors on level design include the properties of a planet (i.e., size, position, speed) and the number of planets.

Planet location: A planet can move in a straight line. We set the speed range to maneuver a spacecraft from 60 to 120 rpm, with the resistance force fixed at 9.2 kp. According to our results, there was no significant maintenance variation under different speeds in the range (here, vertical location). This means that a planet's initial position can be randomly selected from the right side.

Planet size: When determining a planet's minimum size, the designer should carefully consider a controller's characteristics. In particular, we showed that a player's speed tends to fluctuate when performing a maintenance task; nonetheless, for a given target speed, the RMS error is within ±4 rpm. This means that designers should configure the size of a planet by considering the range of RMS error, that is, 8 rpm; if the size is below this range, players may feel that the game lacks controllability.

Planet placement and speed setting: Consider a scenario where there are two planets on the screen. To allow a player to blast both planets, we should properly configure their placement and speed setting to allow sufficient time to destroy both planets. In other words, after blasting one planet, the player should be able to steer the spacecraft to successfully shoot and destroy the other planet. Our pointing task results show that the movement time approximately follows Fitts' law. This empirical model can be used to find the minimum time required to reach the target speed (or target height). For instance, changing from 60 rpm to 120 rpm takes about 4 seconds; thus, the designer can properly configure the planet placement and speed accordingly.

Player tutorial session: According to our results, the exercise bike requires some time for learning when compared with traditional pointing devices. The designer may want to introduce a tutorial level; the goal is to allow users to maneuver the controller skillfully. In addition, data from the tutorial can be used to understand a player's capabilities and provide for more personalized gameplay.

DISCUSSION AND LIMITATIONS

Designing Unique Physical Challenges in Exergames

As stated, providing a consistent sense of controllability throughout game play is important. Exergame designers, however, may intentionally adapt a speed range with inconsistent controllability, to create physical challenges. For example, defeating a boss character in a game is supposed to be difficult. To avoid fire attacks from the boss character, players might be required to pedal at 115 to 125 rpm with a high resistance level. This challenge would be difficult for some players, as the average RMS error at 120 rpm was above 5 rpm. Employing physical in-game challenges can be one unique characteristic of exergame design. It is worth noting that the difficulty of challenges in traditional games is usually controlled by adjusting the complexity of mental tasks, e.g., to make players identify a specific hidden movement pattern of a boss character.

Exercise and Training Perspectives

When considering a player's energy expenditure, the game designer should carefully design or adapt in-game challenges to avoid exhausting a player quickly or failing to achieve a sufficient amount of exercise [14, 16, 39]. For example in the shooter game, it would help to distribute initial positions of planets – the higher the speed (proportional to a planet's height), the higher the energy expenditure.

From the training viewpoint, a maintenance task can be employed in exergames to help exercisers learn an effective pedaling method. It is known that maintaining a steady pedaling speed requires an even distribution of pedaling torque throughout a revolution [20, 35], and this is regarded as an efficient pedaling technique [3]. We envision that more training methods can be adapted in speed-based exergames and thereby effectively provide exercisers with better ways to physically train.

Limitations

We restricted our attention to an exercise bike. In general, existing fitness devices for repetitive exercises (e.g., running, elliptical training, rowing) share similar properties, as mentioned in [31, 32]. Our experiments can thus expand to other fitness regimes. Further user studies are needed to generalize our findings to other devices. We intentionally limited our discussion on game design to action games (particularly shooter games) as many existing exergames belong to this genre [7, 11, 36]. Given our understanding of an exergame controller, exploring alternative genres such as role-playing and simulation would be an interesting avenue for future work. Furthermore, we employed a group of participants in their 20s to promote internal validity of the experiments. Additional experiments with different age groups and physical capabilities are necessary to generalize the results.

CONCLUSION

We evaluated a speed-based exergame controller based on a stationary cycle with a maintenance task and a pointing task and derived the following results. First, the performance of a maintenance task is largely dependent on the difficulty level (e.g., target speed and resistance level), and maintenance error is approximately within a range of 10%. Second, the results of a pointing task with a directional constraint follow a Fitts' law model, but the slope is much steeper than for other devices such as a gamepad and Wiimote. Third, we provided detailed accounts of user experiences in using the exergame controller and illustrated how our findings can be applied to practical exergame design.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Haechan Lee and Bupjae Lee for their assistance. This work was jointly supported by NRF grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2011-0018120), the IT R&D Program of MSIP/KEIT [10041313, UX-oriented Mobile SW Platform], and CMTC of the Agency for Defense Development [1415125561].

REFERENCES

-

Al-Hrathi, R., Karime, A., Al-Osman, H. and Saddik, A. E. Exerlearn Bike: An Exergaming

System for Children's Educational and Physical Well-being. Proc. IEEE ICMEW'12, (New

York: IEEE), 489-494.

-

Coast, J. R., Cox, R. H., and Welch, H. G. Optimal pedaling rate in prolonged bouts of

cycle ergometry.

Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc, 18, 2 (1986), 225-230.

-

Davis, R. and Hull, M. Measurement of pedal loading in bicycling: II. Analysis and

results. J. Biomech., 14, 12 (1981), 857-872.

-

Douglas, S. A., Kirkpatrick, A. E. and MacKenzie, I. S. Testing pointing device

performance and user assessment with the ISO 9241, Part 9 standard. Proc. CHI'99, (New

York: ACM), 215-222.

-

Exergame Fitness: Lightspace Play Wall.

http://www.exergamefitness.com/products/item.php?show=lightspace_play_wall, accessed

August 2013.

-

Fitts, P. M. The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the

amplitude of movement. J. Exp. Psychol., 47, 6 (1954), 381-391.

-

Frevola. http://frevola.com/, accessed August 2013.

-

Fullerton, T. Game design workshop: A playcentric approach to creating innovative

games. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Morgan Kaufmann, 2008.

-

Gao, Y. and Mandryk, R. The acute cognitive benefits of casual exergame play. Proc.

CHI'12, (New York: ACM), 1863-1872.

-

Gerling, K., Livingston, I., Nacke, L. and Mandryk, R. Full-body motion-based game

interaction for older adults. Proc. CHI'12, (New York: ACM), 1873-1882.

-

Göbel, S., Hardy, S., Wendel, V., Mehm, F. and Steinmetz, R. Serious games for health:

Personalized exergames. Proc. Multimedia'10, (New York: ACM), 1663-1666.

-

Guo, S., Grindle, G. G., Authier, E. L., Cooper, R. A., Fitzgerald, S. G., Kelleher, A.

and Cooper, R. Development and qualitative assessment of the GAMECycle exercise system.

IEEE Trans. Neural Sys. Rehab. Eng., 14, 1 (2006), 83-90.

-

Hansen, E. A., Jørgensen, L. V., Jensen, K., Fregly, B. J., and Sjøgaard, G. Crank

inertial load affects freely chosen pedal rate during cycling. J. Biomech., 35, 2

(2002), 277-285.

-

Haskell, W. L., Lee, I., Pate, R. R., Powell, K. E., Blair, S. N., Franklin, B. A.,

Macera, C. A., Heath, G. W., Thompson, P. D., Bauman, A. Physical activity and public

health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine

and the American Heart Association. Med. Sci. Sport. Exer., 39, 8 (2007), 1423-1434.

-

Hernandez, H. A., Graham, T., Fehlings, D., Switzer, L., Ye, Z., Bellay, Q., Hamza, M.

A., Savery, C. and Stach, T. Design of an exergaming station for children with cerebral

palsy. Proc. CHI'12, (New York: ACM), 2619-2628.

-

Hernandez, H. A., Ye, Z., Graham, T., Fehlings, D. and Switzer, L. Designing

action-based exergames for children with cerebral palsy. Proc. CHI'13, (New York: ACM),

1261-1270.

-

ISO 9241-9. Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs)

- Part 9: Requirements for non-keyboard input devices, International Organization for

Standardization, 2000.

-

ISO 9241-411. Ergonomics of human-system interaction - Part 411: Evaluation methods for

the design of physical input devices, International Organization for Standardization,

2012.

-

Konami Dance Dance Revolution. 2005.

-

Korff, T., Romer, L. M., Mayhew, I., and Martin, J. C. Effect of pedaling technique on

mechanical effectiveness and efficiency in cyclists. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., 39, 6

(2007), 991.

-

MacKenzie, I. S. Fitts' law as a research and design tool in human-computer

interaction. Hum.-Comp. Int., 7, 1 (1992), 91-139.

-

MacKenzie, I. S., Kauppinen, T. and Silfverberg, M. Accuracy measures for evaluating

computer pointing devices. Proc. CHI'01, (New York: ACM), 9-16.

-

McArdle, W. D., Katch, F. I. and Katch, V. L. Exercise physiology: Nutrition, energy,

and human performance. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

-

Mueller, F., Vetere, F., Gibbs, M. R., Edge, D., Agamanolis, S. and Sheridan, J. G.

Jogging over a distance between Europe and Australia. Proc. UIST'10, (New York: ACM),

189-198.

-

Mueller, F. F., Agamanolis, S., Gibbs, M. R. and Vetere, F. Remote impact: Shadowboxing

over a distance. Proc. CHI'08 Extended Abstracts, (New York: ACM), 2291-2296.

-

Mueller, F. F., Edge, D., Vetere, F., Gibbs, M. R., Agamanolis, S., Bongers, B., and

Sheridan, J. G. Designing sports: a framework for exertion games. Proc. CHI'11, (New

York: ACM), 2651-2660.

-

Mueller, F. F. and Gibbs, M. A table tennis game for three players. Proc. OzCHI'06,

(New York: ACM), 321-324.

-

Natapov, D., Castellucci, S. J. and MacKenzie, I. S. ISO 9241-9 evaluation of video

game controllers. Proc. GI'09, (New York: ACM), 223-230.

-

Nenonen, V., Lindblad, A., Häkkinen, V., Laitinen, T., Jouhtio, M. and Hämäläinen, P.

Using heart rate to control an interactive game. Proc. CHI'07, (New York: ACM),

853-856.

-

Ohmae, T., Matsuda, T., Kamiyama, K. and Tachikawa, M. A microprocessor-controlled

high-accuracy wide-range speed regulator for motor drives. IEEE Trans. Indus. Elec., 3

(1982), 207-211.

-

Park, T., Hwang, I., Lee, U., Lee, S. I., Yoo, C., Lee, Y., Jang, H., Choe, S. P.,

Park, S. and Song, J. ExerLink: Enabling pervasive social exergames with heterogeneous

exercise devices. Proc. MobiSys'12, (New York: ACM), 15-28.

-

Park, T., Lee, U., Lee, B., Lee, H., Son, S., Song, S., and Song, J. ExerSync:

facilitating interpersonal synchrony in social exergames. Proc. CSCW'13, (New York:

ACM), 409-422.

-

Rollings, A. and Adams, E. Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on game design. Berkeley,

CA: New Riders Publishing, 2003.

-

Schell, J. The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Morgan

Kaufmann, 2008.

-

Seck, D., Vandewalle, H., Decrops, N., and Monod, H. Maximal power and torque-velocity

relationship on a cycle ergometer during the acceleration phase of a single all-out

exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup., 70, 2 (1995), 161-168.

-

Sinclair, J., Hingston, P. and Masek, M. Considerations for the design of exergames.

Proc. The International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in

Australasia and South-East Asia - Graphite'07, (New York: ACM), 289-295.

-

Soukoreff, R. W. and MacKenzie, I. S. Towards a standard for pointing device

evaluation, perspectives on 27 years of Fitts' law research in HCI. Int. J.

Human-Comput. St., 61, 6 (2004), 751-789.

-

Stach, T., Graham, T., Brehmer, M. and Hollatz, A. Classifying input for active games.

Proc. ACE'09, (New York: ACM), 379-382.

-

Stach, T., Graham, T., Yim, J. and Rhodes, R. E. Heart rate control of exercise video

games. Proc. GI'09, (New York: ACM), 125-132.

-

Theng, Y.-L., Chua, P. H. and Pham, T. P. Wii as entertainment and socialisation aids

for mental and social health of the elderly. Proc. CHI'12 Extended Abstracts, (New

York: ACM), 691-702.

-

Warburton, D. E., Bredin, S. S., Horita, L. T., Zbogar, D., Scott, J. M., Esch, B. T.

and Rhodes, R. E. The health benefits of interactive video game exercise. Appl.

Physiol. Nutr. Metab, 32, 4 (2007), 655-663.

1 kp denotes kilopond, or kilogram-force, a gravitational metric unit of force.