“Beauty Will Save

The World!”:

Feminine Strategies in Ukrainian Politics and the

Case of Yulia Tymoshenko

September 1, 2005. The traditional annual celebration of the “first bell” takes place at the primary school of Sosnivka, a small coal-mining town in Western Ukraine.[1] The first-grade students are presenting a short performance. A tiny girl, Darynka, dressed in a lacy skirt, a red jacket with a downy collar and a wrap-around braid (borrowed by her grandmother from a beauty salon especially for the occasion) comes to the front. She recites with special expression a poem written by her female teacher:

To be Prime Minister is my aim,

I am already skilled in braiding.

Designer clothes will be mine,

I’ll master all that is

taught![2]

Stormy applause. Darynka rings a little bell signifying that the school year has begun. After the ceremony she finds herself encircled; everybody wants to have a picture taken with this little copy of the great Yulia. Darynka is happy: today she is almost as popular as her famous prototype.

One can hardly find another politician in Ukraine who produces such a tremendous emotional reaction among citizens (either for or against) as Yulia Tymoshenko. Indeed, Tymoshenko remains very popular in Ukraine as the last parliamentary elections in March 2006 proved: her party’s bloc BYuTy won in 13 of 25 regions.[3] In Lviv just before the elections one could observe ordinary people standing in long queues to get a poster or a postcard portraying their idol. Portraits of her made out of amber are sold in fashionable gift shops downtown. As one of the most recognizable symbols of Ukraine, a number of souvenirs depicting Tymoshenko (matryoshka dolls, commercial paintings, handcrafts, etc.) are sold at tourist places

.

Lviv city dwellers queuing up in front of the Tymoshenko’s electoral campaign tent; photo by Oksana Kis, Lviv, March 24, 2006

Souvenir matreshka dolls representing the “Orange Coalition”; photo by Oksana Kis, Lviv, summer 2005

She has a fan club in the city of Vynnytsia, there is a statue of her in the Museum of Wax Figures in Kyiv (along with one of Victor Yushchenko), and a museum devoted to Yulia Tymosenko was conceived of in Lviv last summer (which remains, however, in the planning stages). She always finds new ways to agreeably surprise people, such as on the occasion of the first anniversary of the Orange Revolution on October 22, 2005 at Maydan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv, when she did not mount the platform in the usual way using the stairs, but the crowd brought her there on its hands – a gesture meant to demonstrate that she is the only genuine leader with the people’s support in Ukraine. Today it is hard to ignore the smiling portraits of her in shop windows and business offices in Lviv. Many people even have an image of Tymoshenko in their private apartments. Indeed, she has found her way into peoples’ hearts. She is popular in the true sense of the word.

How to explain this impressive success of a female politician who has been in the opposition for most of her career? What is so special about this woman? What are the reasons for her unusual popularity? This article tries to deconstruct her political image in order to reveal the secrets of Tymoshenko’s success.

The Ukrainian Context

A short introduction to the post-Soviet gender order in Ukraine seems to be essential in beginning such an analysis. When Ukraine became an independent state in 1991, the new national leaders proclaimed their intention to establish democratic governance and the development of a civic society based on the principle of universal equality of all Ukrainian citizens in their rights and opportunities. Over the last fifteen years substantial changes have occurred in public and political discourses, including in Ukrainian women’s consciousness. The formerly imposed canon of femininity – the communist ideology of the Soviet Superwoman – lost its monopoly and authority and was challenged and undermined by Ukrainian nationalism and consumerism.

The value system of the formerly forbidden ideology of Ukrainian nationalism is deeply rooted in Ukrainian national history and folk culture, so it naturally supports the revival of the traditional gender order. So-called “Western patterns,” including such manifestations of consumer culture as industries of beauty and fashion, were formerly hidden from Soviets behind the “iron curtain.” Perceived as an incarnation of “real” Western freedom and genuine femininity, they attracted Ukrainian women. The ideologies of nationalism and consumerism have produced two predominant models of normative femininity, which can be labelled Berehynia and Barbie and correlate to each other as national vs. cosmopolitan or as local vs. global versions of femininity.[4]

Although the Berehynia image has a rather heterogeneous nature representing a constellation of certain pagan beliefs, elements of matriarchal myth, some Christian ideas,[5] popular folk motifs and features of some characters in Ukrainian fiction, it pretends to be an embodiment of a native femininity, enrooted in and arising from authentic ancient Ukrainian history and national culture. As a single whole it fits perfectly into the ideology and mythology of Ukrainian nationalism, supporting a corresponding value system. The core elements of the Berehynia image are self-sacrificial motherhood, Christianity and devotion to the nation. It is also important that Berehynia has certain matriarchal implications, which encourage a woman to be dominant, competent and decisive but only within her proper domain of competence.

The second image – that of Barbie – is closely associated with market ideology and consumer culture. The Barbie doll remains one of the most obvious symbols of globalization in post-Soviet countries. The Barbie model derives not only from the doll that bears this name but also from a lifestyle associated with it. Beautiful, sexy, charming, and correspondingly turned out, a “Barbie woman” is designed to attain success as a pleasant, attractive toy for a man. For many, Barbie embodies the ideal of heterosexual femininity today.

Unlike Berehynia, who is assigned mainly the (natural and cultural) reproduction of the nation, Barbie’s body is an object of male aesthetic and erotic pleasure. In both cases, however, a woman is to serve – either a man or a patriarchal nation-state. These two well-established stereotypes of femininity impose on a Ukrainian female politician a number of limitations and requirements to comply with in order to be accepted by ordinary people and gain electoral support among citizens. A woman interested in a political career in Ukraine is expected to fulfil at least two roles: as Berehynia she has to become a virtuous mother of her nation; as Barbie she must be a national sex symbol.

Climbing the political Mount Olympus

Yulia Tymoshenko’s life has not at all been easy. She is by no means the Cinderella of Ukrainian politics; she did not get her chance from a fairy godmother. Quite the opposite – her life story, as it is told in her autobiography and other Tymoshenko’s biographies recently published in Ukraine, proves her to be the single-handed designer, architect and builder of her destiny.[6] Indeed, she has come to be known as an entirely self-made woman, steadily laying a path from poor provincial girl to prime minister and one of the most famous women in the world. Let’s trace the changes she made to her image to survive her ascent up the Ukrainian political Olympus.

Yulia was born in 1960 into an ordinary Soviet family in Dnipropetrovsk. She was the only child. Her father left them when she was a little girl, so Yulia’s mother took several jobs in order to maintain the family Thus from the young age Yulia learned that a woman must be strong in order to survive. She knew there was nobody to draw her out of poverty so she studied diligently at school and entered university. In 1979 she met her husband Alexander and, despite their very young age, soon married.[7] The next year she gave birth to their daughter Eugenia. At the same time she continued her university studies and graduated in 1984, working first as an engineer in a factory and then later starting up a small private business with her husband. Owing to her expertise in economics and her strong character, Yulia gained authority in business circles; she became an important figure in her husband’s family business. In 1995 she headed the United Energy Systems corporation – the richest and most influential company on the market in energy resources in Ukraine (its yearly turnover then ran into the billions). At that time Tymoshenko was regarded as the protégé of Prime Minister Pavlo Lazarenko.[8]

In 1997 she was elected to the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian Parliament) in a by-election; in 1998 she was elected as a people’s deputy for the second time. Her career was developing headily. In 1999 she completed a doctoral thesis in economics and received the degree of kandydat nauk. In the same year she was assigned the post of Vice Prime Minister in the Yushchenko-headed government. But Tymoshenko was not satisfied with her success as an economist. In 1999 she founded and headed a party of her own, namely Bat’kivshchyna (Fatherland). The party enjoyed some favor, and a few years later constituted the core of political opposition to the Kuchma regime. That is why a criminal case against her was fabricated and she was jailed for 42 days in 2001. Nevertheless, Tymoshenko did not give up or in, and in 2001 she founded and led a coalition of parties bearing her name: Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko (BYuTy). The Bloc’s electoral campaign in 2002 was quite successful, and Yulia Tymoshenko became a member of the Ukrainian Parliament for the third time.

Tymoshenko belongs to the central-right wing of Ukrainian politics, advocating liberal principles in market economy and promoting the further democratization of Ukrainian society.[9] However, her decisions as Prime Minister seemed to evidence more of a socialist approach to the state regulation of the national economy.[10] On the other hand, Tymoshenko invariably represents herself as an oppositional politician fighting a corrupted regime. Tymoshenko’s rhetoric is always highly populist; when addressing a wider audience, she constantly stresses her devotion to restoring social justice and to solving the most burning social issues. As Andrey Slivka has correctly remarked, “Tymoshenko’s statism and populism do have appeal in a country in which even the young are not completely convinced of the need to jettison the entirety of their socialist inheritance.”[11]

Tymoshenko’s alliance with Yushchenko during the 2004 presidential campaign brought him a good many votes. Her role in the Orange Revolution can hardly be overestimated. As a reward, the new President, Yushchenko, assigned her to the post of Prime Minister in February 2005. She was discharged in September 2005. An analysis of the efficacy of her governance is not the purpose of this study. Despite this failure, Tymoshenko has not been written out of the Ukrainian political game; she is still a very respected player, and the peculiarities of her play are of our special interest here.

In what follows I analyze how and to what measure Yulia Tymoshenko makes use of stereotypical female images. Tymoshenko is different every time you see her. She looks different, she speaks differently, and she behaves differently depending upon the political context, the particular situation and the audience being addressed.[12] What is invariable in her behaviour is that she performs each role – both Berehynia and Barbie – skilfully and with deep persuasion.

Mother of the Nation

Tymoshenko softly but steadily has promoted her image as Mother of the Nation. In response to the question of who her political “father,” “mother,’” “husband” and “children” are, Tymoshenko stated: “I wish to join people who have the same goal as I do. That will be the family.”[13] Elsewhere she develops this idea: “I perceive a woman in the political realm as a mother who defends her children... Maybe at first glance she looks unprotected, but you better not hurt her children....”[14] One can discern Tymoshenko’s maternal attitude toward the Ukrainian people in the greetings she has published on the occasion of holidays (national, Christian, professional, etc.). The word “warm” (as an adjective or as a verb) appears in many such congratulatory texts, e.g. “may the care of... people who love you warm your hearts,”[15] “accept my warm greetings,”[16] “autumn brings us warm recollections of light-hearted days,”[17] “may Easter... warm our souls with blessed warmth,”[18] etc. (italics added). This verbal message is usually supported by visually as in the 2002 posters and wall calendars picturing Tymoshenko in a white warm sweater with the inscription “May your next year be warm!”

Indoor wall calendar / outdoor poster

published and disseminated by BYuTy, Ukraine, December 2002; inscription:

“May your next year be warm! Yulia Tymoshenko”

The notion of warmth in Ukrainian popular discourse is deeply associated with a mother’s body, especially in conjunction with such words as love, care, safety, good, and peace, which are often present in Tymoshenko’s holiday greetings and her party’s ads.[19] The new logo of Tymoshenko’s 2006 electoral campaign – a red heart against a white background[20] – is a symbolic representation of the idea of selfless and cordial maternal love. Maternal implications are often articulated in Tymoshenko’s rhetoric. For instance, she usually addressed people in her public speeches on Maydan Nezalezhnosti at the time of the Orange Revolution in Kiev as “my kinsfolk.” A male politician could be hardly imagined profitably using such rhetoric or symbols to address his electorate in Ukraine.

Tymoshenko also behaves like a mother with her employees (her secretary, chauffeur, etc.), and this behavior is understood in exactly that way. Indeed, people put their impressions upon meeting Tymoshenko in almost the same words: “She always addresses them with tender names; it seems to be warm family relations.”[21] People seem to feel her warmth. On Tymoshenko’s personal website one can find a letter from a certain Nadia, who shares her impressions of attending a meeting with Tymoshenko in 2002: “[Tymoshenko] shines with warmth and joy... she radiates energy... It was like a sunrise...Yulia illuminated and warmed the souls... I felt warmed in my heart”[22] (italics added). Strikingly, three years later another female journalist noted: “she radiates a powerful positive energy... she is blazing, and that lightens, warms and cheers the people around her”[23] (italics added).

As Joan Landes has noted, “Women are constituted as political subjects in the new nation not only through the practice of motherhood but also in and through the complicated process of visual identification with iconic representations of virtue and nationalism.”[24] Tymoshenko is a good example of this. The image of the Ukrainian nation’s mother is visualized by means of her distinctive wrap-around braid hairstyle.[25] In popular discourse such a hairstyle is closely associated with the traditional image of mature woman, particularly a mother, i.e. Berehynia and her matriarchal implications.[26] Adopting such a “new” look was an effective ploy. It not only helped Tymoshenko to emphasize her political pro-Ukrainian-ness; it also stressed her distinctiveness among Ukrainian politicians. The plait makes Tymoshenko easily recognizable and presumably, the folk origin of this hairstyle resonate positively with traditionally oriented ordinary people.[27]

It was while she was a people’s deputy in Parliament that Tymoshenko began gradually softening her image. In 2004 she seldom wore a plait, preferring slightly curled, loose and lightened hair instead. In fall 2004, at the time of the Orange Revolution, Tymoshenko usually appeared on Maydan bareheaded, but she still showed up in her trademark plait on official occasions. The plait became an object of jest especially during and after the Orange Revolution. For example, such mockery could be found in the summer 2005 on Lenin Square in Donetsk, which is the permanent meeting place of Viktor Yanukovych partisans. They compared a plait with an evil tool endangering Ukraine. In Russian the word kosa simultaneously means a “plait” and a “scythe.” This play on words allowed an anonymous author to call her “raw-boned with a scythe,”[28] i.e. the grim reaper. The Narodnaya Opozitsiya bulletin published a caricature with Tymoshenko’s plait as a noose strangling the Ukrainian economy. Another Ukrainian magazine featured a cover with a picture of snake-like plaits coiling around Yushchenko.[29] Someone’s desire to wear a hairstyle “à la Tymoshenko” was interpreted as one of the “orange plague” symptoms in need of vaccinating against.[30] Such metaphors attach infernal implications to Tymoshenko’s image. Like any Great Mother-Goddess in ancient myths, Tymoshenko’s image is essentially ambivalent; via her plait it obtained its second – mortal – representation in accordance with the basic principles of mythology.

In terms of ethnicity, Tymoshenko’s Ukrainianess is rather questionable. Her maiden name was Grygian, which is usually of Armenian origin. Russian is her native language, and she spoke Russian most of her life. In the late 1990s Tymoshenko was quite popular in the Ukrainian southeast. But to become a national leader Tymoshenko had to be recognized in the Ukrainian-speaking and nationally oriented western regions as well. She knew that no Russian-speaking politician had a chance to become popular in that region so she learned Ukrainian, and since 2000 she has only spoken Ukrainian in public. She thus won the favor of western Ukrainians, and they now constitute the majority of her electorate.

Currently Tymoshenko’s team’s strategy is trying to secure her legitimacy as the leader of the Ukrainian nation by establishing imaginary ties with ancient Ukrainian history and culture. In 2005 the Lviv regional branch of the Fatherland party started publishing a newspaper Nasha Batkivschyna (Our Fatherland). The golden Scythian neckpiece – the invaluable ancient masterpiece of Ukraine – was chosen to be its logo. “Just like this neckpiece Yulia is our most valuable treasure and our national pride,” explained Mr. Semen, the vice-head of the Fatherland Lviv regional branch. In an article entitled “The Heritage with Deep Roots,”[31] Bohdan Mykhaliunio discusses the historical continuity between this newspaper and various periodicals with similar titles published by the Ukrainian national intelligentsia in the Habsburg Empire and Poland in the nineteenth century. “Yulia Tymoshenko is the first woman since Princess Olga[32] to run the Ukrainian government,” one could read in Tymoshenko’s pre-electoral leaflet in 2006. Such historical references are intended to reinforce the impression of Tymoshenko’s “native” Ukrainian-ness.

A National Heroine

Tymoshenko’s slender, delicate figure (she is less than 160 cm in height and wears a size 38) belies her rather tough style of management (because of which she has a reputation of being “the only man in Ukrainian politics”). The mass media usually stress the contrast between the immutable feminine loveliness of Tymoshenko’s appearance and her enormous energy, lofty political ambitions, purposefulness, resolution, and strong will, which are not usually associated with traditional femininity.[33] The German magazine Focus eloquently named her an Iron Angel.[34] “There is a mighty Slavic tank inside this Slavic figurine!” claimed a famous Ukrainian philosopher and historian Vadym Skurativsky. “This is the unique combination of a cool mind and a feminine charm! echoed another respected scholar, Myroslav Popovych.[35]

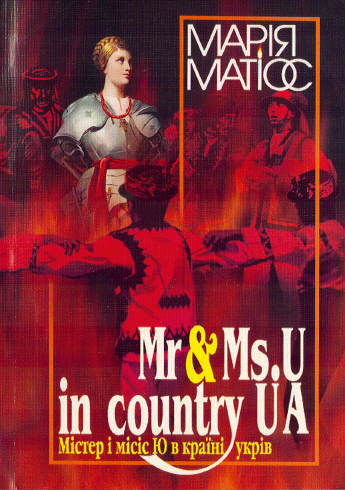

The combination of exterior delicacy and interior strength, feminine appearance with masculine conduct, soft female sensibility with tough male character makes Tymoshenko comparable to the French heroine Joan of Arc, and the international mass media has not overlooked this quite obvious similarity. In 2001 the Canadian Ukrainian weekly Mist published a photo-collage portraying Joan of Act with Tymoshenko’s head and the caption: “Recently the Canadian press called Tymoshenko ‘the Ukrainian Joan of Arc.’” In the Ukrainian nation-state milieu she is known as “the only Cossack among the Ukrainian deputies.’[36] The image chosen for the cover of the satirical novel Mister and Missis Yu in Country UA by Maria Matios (2006) was of a woman in a wrap-around plait, vested in armor, in the middle of a bonfire surrounded by Ukrainian men in traditional garments dancing the arkan battle dance.

The cover of the book ‘Mr and Ms U in

Country UA’ by Maria Matios (Kyiv, 2006)

In September 2006 the Ukrainian magazine Fokus designed its cover with a portrait of Tymoshenko vested in armor a la Joan of Arc, and “that pure personification of patriotism” remains Tymoshenko’s own personal favorite heroine, as she confessed in 2005 to a journalist at Le Monde.[38] As one might expect, Tymoshenko’s enemies have not passed over this heroic image. On the contrary, they have turned it into an object of black humor. One such joker asked: if “Yulia Tymoshenko is the Ukrainian Joan of Arc, when is she to be burned at the stake?”[39]

There are many variations in naming the militant femininity of Yulia Tymoshenko: an Iron Lady, an Amazon, a Warrior Princess, a Revolutionary Princess, the Ukrainian Marianne, and a Samurai in a skirt[40] – these are just a few examples. As Marian Rubchak commented, “the militancy that Tymoshenko has shown in battle to defend herself and attack the government has been a route back to public favor and, during the Orange Revolution, to the peak of her popularity.’[41] Although Tymoshenko constantly stresses her pacifism (“Fighting someone is not my aim... Actually, I am a very peaceful person...”[42]), her deeds reveal a disposition towards radical action. After her dismissal nobody believed that she would fall into oblivion; rather the Ukrainian media discussed her possible revenge and portrayed her as a warrior.[43] Tymoshenko does not avoid this aggressive image. During the Orange Revolution Tymoshenko clambered up on a truck blocking the way to the president’s residence and called people to follow her example, and naturally she was then compared with Delacroix’s famous painting “Liberty Leading the People.” In fall 2004 she often appeared in clothing that stressed her revolutionary mood: her black leather jacket in the style of the Bolsheviks in 1917 and gaudy orange sweater with the inscription “revolution” spoke for themselves. Finally, her 2006 electoral poster represented her as a representative of the “Army of the Light” (from the popular blockbuster Night Watch): Tymoshenko appears in an aureole dressed in a black leather coat holding a sword. “Get out of the darkness everyone!” the inscription says.

Poster from the BYuTy parliamentary electoral campaign, Mar. 2006

Upon becoming leader of the opposition, Tymoshenko promised to commit all her resources to fighting Ukraine’s inner enemies (namely the oligarchy) and to rooting out corruption. “A sense of responsibility provides me with the strength to keep resisting. Moreover, there is no power able to stop me,”[44] Tymoshenko claimed in 2001 when under heavy attack. As Tymoshenko cannot but be aware of the masculine coding of her tough behavior, one can conclude that she regards it as indispensable for a successful political career, especially for a politician in the opposition.

A Victim / a Martyr

The image of national heroine is occasionally transformed into a variation: that of victim or martyr, something which routinely took place in 2001-2002 when Tymoshenko was persecuted the most. When she was jailed in the course of the 2002 parliamentary electoral campaign, flyers and a booklet picturing her as a victim of a corrupt regime appeared immediately. Those pictures portrayed an ill, haggard and tired-looking female martyr.

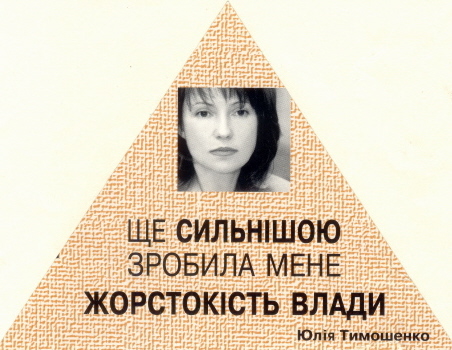

A sticker disseminated during

Tymoshenko’s detention, spring 2001; inscription:

‘The

regime’s brutality made me even stronger!’

A few years later, when she was suddenly discharged as Prime Minister, she came to the last session of her government in exactly the same way. With shadows under the eyes and no make-up on her face, Tymoshenko looked tired, hurt and miserable, thus encouraging empathy for her as the victim of an unfair and unequal struggle for justice.

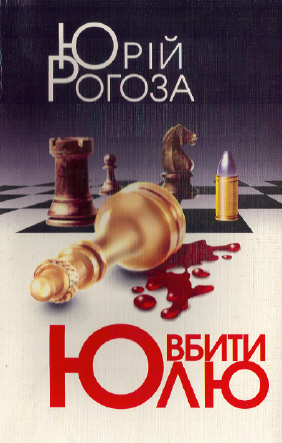

Tymoshenko’s political publicity countered the charges of crimes attributed to her and described instead her numerous moral virtues as a new people’s interests advocate. “The regime’s severity made me even stronger” says one of Tymoshenko’s flyers in 2001. Tymoshenko’s self-sacrificing dedication to her political vocation – namely the Ukrainian nation’s better future – has been described in detail in the essay with a very eloquent title ‘Yulia Tymoshenko’s Crown of Thorns.’[45] A detective story by Yuri Rogoza with the even more provocative title The Unperformed Order came out at the same time.[46] The novel relates a conspiracy of high-rank officials aimed at the political assassination of Yulia Tymoshenko. In 2006 the same author published a “non-documentary” novel (which is actually a sequel to the previous one) under the more explicit title Killing Yulia.[47]

A novel ‘Killig Yulia’ by Yuriy Rogoza (Kyiv, 2006)

In both works the image of Tymoshenko as a victim-martyr is being actively constructed, and verbal messages are reinforced by impressive visual ones as the cover of the latter book features an overthrown golden chess queen with a wrap-around braid which is bleeding on the chess board.

Political commentators have noted the use Tymoshenko has made of the image of the victim-martyr in constructing her political image as a fighter for the nation’s welfare,[48] and also the success that this method has had on ordinary people.[49]

A political cartoon by Oleh Smal’, exhibited in Lviv in Dec. 2005

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church (of the Moscow Patriarchy) awarded Tymoshenko an insignia of St. Barbara the Great Martyr in 1998, and Tymoshenko wore this decoration on all official occasions up to her imprisonment in 2001 and mobilized religious discourse in which she figured as an envoy of God assigned to fight Evil, namely the regime of a corrupt oligarchy:

Yes, I am a believer. All of my family members were believers, I mean, even before the collapse of the Soviet Union. I believe in God and I feel Him intuitively, He is in my heart. I realize that my present-day struggle is a duel between good and evil. A very difficult fight... We are the army of Good, and we have to do all our best to win, even if we are crucified or killed for that.[50]

Perhaps, Illia Panyok, a Ukrainian painter from Kharkiv, was inspired by this rhetoric in deciding to create a monumental canvas titled “Sacred Duel” picturing Yulia Tymoshenko in the role of St. George defeating a dragon.[51]

“Sacred Duel” painting by Illia Panyok, exhibited in Kyiv in Mar. 2007

A Faithful Christian

As clearly apparent in the previous example, the role of victim/martyr is closely related to the Christian virtue of self-sacrifice. It is not accidental that after the Orange Revolution Tymoshenko was deemed the Goddess of the Orange Revolution,[52] the Icon of the Orange Revolution, and the Slavonic Madonna.[53] These monikers resulted from the careful work and clever strategy of Tymoshenko’s team. She is never as obvious in presenting her religious persuasions as most of her fellow politicians.[54] Rather Tymoshenko’s image as a good Christian is built from little details and remarks dispersed here and there: “I am an Orthodox Christian, I do not believe in such symbolic things [as horoscopes],” Tymoshenko stated in one interview.[55] Elsewhere she went further: “I am really a believer. I communicate with God every minute of my life, therefore everything I do I try to reconcile with the moral principles of Decalogue.”[56]

For Tymoshenko Christianity is not only a personal affair – it is a precondition of Ukraine’s welfare. Tymoshenko’s vision of Ukraine’s future is heavily based upon Christian thought; it bears the imprint of messianism, so the role of Yulia Tymoshenko in that utopia is rather clear:

Currently I am writing a book about the ways human civilization has developed. That is why I study the Bible thoroughly. It says a lot about how to harmonize life... Faith is a way of life. Despite all of life’s severities, God says ‘Believe and do not fear’... I am confident that Ukraine’s vocation is to fulfill its historical mission, namely to provide the world with a new example of a rightful society.[57]

As a politician Tymoshenko understands and accepts the Christian dimension of her people’s mentality, so she has to fulfill their religious aspirations. One of her biographers wrote: “Yulia Tymoshenko is an earnest and faithful Christian. She claimed that ‘Ukraine will never rise from its knees until it kneels to the God.’”[58] (bold in original). In this context it is quite natural that Tymoshenko never forgets to publish her congratulations to Ukrainian citizens on the occasions of Christmas and Easter in the mass media.[59]

An Easter flyer printed and disseminated by the Lviv Regional Branch of Batkivshchyna, Lviv, Spring 2005

The Lviv regional branch of Tymoshenko’s Fatherland party published and distributed an Easter flyer in spring 2005 in which Tymoshenko’s portrait appears side-by-side with a picture of traditional Ukrainian Easter bread and symbols, religious congratulations and wishes. Thus some additional national-religious meanings are injected into her political image. And the action was clearly popular – one could find flyers exposed on shop windows long after Easter (in June-August 2005).

The images on her personal website of Tymoshenko holding a Christian icon, listening to a priest’s lesson, and praying in a church would also seem to reinforce her image as a proper Christian. Tymoshenko’s hairstyle strengthens not only the maternal (or matriarchal) implications of her image, but it bears a clear resemblance to the Christian iconography as well. Some commentators have suggested that her plait resembles a halo, and for many Tymoshenko looks like a Christian icon.[60]

The idea of the divine in Tymoshenko’s image is not completely unambiguous. One portrait of her, for example, in the local headquarters of the Lviv regional branch of the Fatherland party, is situated on the wall behind the desk of the Chief, a place of great honor that was usually reserved for a Christian icon before socialism and for the portraits of Communist Party leaders (Lenin, Stalin, Brezhnev etc.) in Soviet times.

A portrait of Tymoshenko decorating the office of the Head of Lviv Regional Branch of the ‘Batkivshchyna’ Party, photo from Tymoshenko’s personal web-site www.tymoshenko.com.ua Oct. 30, 2003

Tymoshenko’s portrait resembles the images of female prophets and/or healers in Ukrainian newspaper advertisements: a straight-looking gaze, a blessing/edifying shape to the hand, and a wraparound purple plait/veil. Such a representation implies Tymoshenko’s extraordinary spiritual potentialities. Another controversial image is also reproduced on a Christmas poster (a wall calendar), which I found in a hall in the headquarters. Tymoshenko appears as a fairy able to fulfill dreams: “Make a wish!” the inscription says. The children sledding in the background strengthen the effect of this omnipotent mother-enchantress. Such a fusion of pagan and Christian elements in Tymoshenko’s image is quite natural inasmuch as it reflects the syncretism of popular beliefs among Ukrainians, especially regarding the symbolic representation of femininity, as research by Marian Rubchak has demonstrated.[61]

An indoor wall calendar printed by Lviv Regional Branch of the ‘Batkivshchyna’ Party, Lviv, Dec. 2003

A Stylish Lady

The aesthetic dimension is perhaps one of the most important aspects of Tymoshenko’s image. It is true that ordinary Ukrainian people, consciously or not, first started liking Tymoshenko for her beauty. “She is such a pretty woman!” a middle-aged colleague of mine, an advanced scholar and political activist, commented in explaining his switch from another party to Fatherland. “The beautiful choice!” stated a cover of the Korespondent magazine (#3, January 29, 2005) dedicated to Tymoshenko’s appointment to the post of Prime Minister. Even the abbreviation of her party’s coalition name - Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko, BYuTy is usually read as “beauty.”

So it was not surprising when a revolutionary poster/wall calendar featured a smiling Tymoshenko offering flowers to the special armed guard along with the slogan “Beauty will save the world!” That slogan proved to be quite congruent with people’s expectations regarding the mission of a woman in politics. It is also noteworthy that the Russian version of the slogan could be read as “Beauty will save the peace,”[62] which echoes the stereotypical perception of women as peacemakers. The slogan was replicated elsewhere (e.g. on postcards), and the poster itself was used as a political banner at the time of the Orange Revolution.[63] To defeat evil using the power of beauty – is not that the Ukrainians’ expectations regarding the mission of a woman in politics?

Over the last years Tymoshenko gained fame as a fashion trendsetter in Ukraine and abroad; her taste in clothing is almost beyond question (despite the consensus that her style is rather eclectic). From the very beginning of her political career people mentioned her predisposition towards elegant, fashionable, quite expensive garments and high-heeled shoes (one newspaper even nicknamed her “Yulia – white shoes”[64]). Relatively recently, however, Tymoshenko has become more trendy in her tastes. The changes to Tymoshenko’s entire image over the last decade reflect the twists of her political career.[65] These transformations resemble the stages of a butterfly’s transmutation: first, it has the shape of a regular caterpillar, then it turns into a hard chrysalis, and finally a beautiful multicoloured being appears. At the very beginning of her ascent onto political Olympus (in the mid-nineties) Tymoshenko was merely a delicate, smiling woman wearing light-coloured dresses and flowing hair, as photos from that period show.[66] But in order to assert herself as a skilled gamer at the political table, Tymoshenko had to change her image. She began appearing as a serious businesswoman dressed in a dark tailored casual suit; her hairstyle changed as well – it became shorter and more severely cut. At the beginning of 2001 Tymoshenko’s hair grew again, and in fall 2001 she suddenly started wearing her signature wraparound plait, a rather courageous step since no Ukrainian politician had ever changed his/her appearance (and the whole style) in such a radical way before. The traditional hairstyle of a Ukrainian married women betokened Tymoshenko’s political maturity; now she was a ripe politician confident of her power. That was a sign that Tymoshenko was ready for an open fight.

When Tymoshenko became Prime Minister at the beginning of 2005, she started paying particular attention to her appearance. Earlier she claimed that black and white were her favorite colors of clothing, but after she became a people’s deputy and especially after her appointment as Prime Minister, her clothing became significantly more colorful. A number of dresses in red, pink, violet (let alone orange) enriched her wardrobe. The mass media in Ukraine and abroad vied with each other in discussing her appearance. Tymoshenko became the main Ukrainian newsmaker not only because of her political and governmental activities but also because of her garish garments, and this is despite her statement of 2003 that “politicians cannot... walk into Parliament as though on a catwalk. People should distinguish between catwalk and Parliament, but whether one appears on catwalks or in politics, one should still look nice.”[67] Tymoshenko’s appearance broke all well-established dress codes. Indeed, the numerous very womanish details of her dresses (artificial flowers, accordion pleats, ruffles, puffed sleeves, etc.) are hardly associated with the reserved business suits female politicians usually wear.

One might assume that Tymoshenko consults a professional image-maker regarding garments, but in fact nobody has never heard about or seen such a person.[68] Ayna Hase, Tymoshenko’s tailor, claims: “She participates very actively in the creation of her garments. I guess Yulia Volodymyrivna decides independently what to wear on this or that occasion.”[69] As is typical of female decision-makers, journalists pay much closer attention to Tymoshenko’s wardrobe than to any of her male colleagues’.

Newspapers’ publications discussing Tymoshenko’s appearance, 2005

In summer 2005, one newspaper celebrated Tymoshenko’s two hundredth dress and devoted two pages to telling readers about her preferences in clothing.[70] Another journalist spent a great deal of time calculating how much Tymoshenko’s garments cost. Tymoshenko’s enemies have also not passed over this issue in silence. They reinterpreted her stylish image as a mask covering her (allegedly) corrupt, criminal face. The following verse was published in a newspaper associated with the Ukrainian Progressive Socialist Party:

Yulia, please

come in new clothing

High-heels pressing in the floor

–

Interpol’s most ardent desire

is to embrace you and

then ask for more.

You remember, in this season

Your best color is a

hit

...Later in a women’s prison

You’ll be the leading

zhensoviet.[71]

A Sexy Woman

In 2005, when Tymoshenko was at the peak of her career thus far, the newspaper Argument Gazette published the results of a poll aimed at revealing how sexualized the images of Tymoshenko and Yushchenko in popular opinion are.[72] Although the results are more than modest (only about the quarter of male respondents like Tymoshenko and less that 1% of them has related erotic fantasies[73]), the mere fact of asking such questions is indicative.

It was in any case by no means the first time Tymoshenko has been discussed as a sex symbol. In 2001 Tymoshenko was quoted as remarking in passing that “appearing on the cover of Playboy magazine is the best choice of any woman, but she herself does not fit its standards.”[74] The media immediately labeled her a “new sex symbol.” In December 2004 the men’s magazine FHM assigned Tymoshenko ninth position on a list of the world’s hundred sexiest women. In May 2005 the woman’s magazine ELLE Ukraine featured Tymoshenko on its cover and published an interview and a series of photos of her in fashionable clothing. In June 2005 the Polish edition of Playboy titled Tymoshenko “woman of the month” and published a photo of her decently clothed. These examples provoked a real storm in the media; only lazy people did not comment on them.[75]

The mass hysteria around Tymoshenko’s lure reached its peak in autumn 2005 following her dismissal from the post of Prime Minister. First, the premiere of the erotic movie Yulia took place in Moscow.[76] As evident in the name, Yulia Tymoshenko was the most likely prototype for the main character, and, indeed, the young sexy girl, who often appears naked in very outspoken situations, bore a striking resemblance to a certain female Ukrainian politician with a wraparound plait and the same name. Alexei Mitrofanov, a deputy in the Russian Parliament, who produced and wrote the screenplay for this movie, assumed that it would contribute to a rise in Tymoshenko’s ratings in the course of the elections.[77] However, Tymoshenko’s opponents in Ukraine tried to use her sexy image to compromise her. They printed and disseminated in the city of Kirovohrad thousands of flyers picturing a bare-headed and naked Tymoshenko with inscriptions “Yulia, we love you!” and “Why is your braid unplaited?”[78] Tymoshenko’s female attributes give no rest to artists of all kinds. For instance, Andrey Budayev, a Russian artist, created a series of paintings (“Waiting for Eden,” “Abduction of Europa,” etc.) where Tymoshenko appears naked in the role of a nymph (exhibited in Moscow in January 2007); Alexander Lydahovsky, a Ukrainian artist, made a bronze sculpture of Tymoshenko’s head (exhibited in Kyiv in March 2007); while a female painter from Saint-Petersburg, Vira Donska-Khylko, created a monumental canvas “Rubliovsk Highway” on which Tymoshenko appears naked in the company of twelve other well-known women (mostly from show-business).[79]

A Companion or a Doll

Tymoshenko’s appearance attracts people, especially men, and Tymoshenko herself is quite aware of it. She tested her powers in this regard during a tense meeting with the Chief of Gazprom (the Russian state gas enterprise), Rem Viakhirev, in 1995 by coming to a meeting in a short skirt and jackboots, and won his favor. Later Tymoshenko’s appearance caused many male officials confusion. Soon the media started calling her Lady Yu[80] in analogy with Lady Di (Princess Diana).

The perception of Tymoshenko’s striking appearance among her male colleagues varies. Some interpret it as a manifestation of “her ability to break stereotypes and to introduce innovations” in the political realm (Yuri Kostenko); others are aware of the impact of her feminine charm on male politicians but don’t mind: “inasmuch as it works she may use it for Ukraine’s good” (Volodymyr Yavorivsky);[81] “Men like her a lot. She knows that and uses her woman’s advantages for political purposes”[82] (Alexander Holub). And Tymoshenko has in fact admitted that she uses “female tricks” when needed.[83]

Ukrainians are not accustomed to seeing a woman as an autonomous and self-sufficient political agent. When she first began in politics, Tymoshenko was often perceived as a protégé, and she worked hard to allay this association. When she became a member of the opposition, people preferred to regard her as a partner or an assistant to the male oppositional leaders. Experts of all kinds regard the pair Yuschenko-Tymoshenko as exemplary of partnership in Ukrainian politics. Socio-psychologists rate the tandem as very efficient and strong because each partner complements and balances the individuality of the other in terms of their masculine-feminine traits.[84] Their teamwork was successful when Tymoshenko was Vice Prime Minister in Yuschenko’s government in 2001; they also proved to be a good team during the presidential campaign of 2004 and they continued to cooperate as President and Prime Minister in 2005. They resemble a mythical demiurge couple, in which male and female principles are in perfect harmony. This allusion arises from both visual and verbal messages. In December 2004 the newspaper Ukraina Moloda published an article about Tymoshenko with the quite indicative title ‘The First Lady of Revolution,”[85] although this title should refer to Kateryna Chumachenko, Yuschenko’s wife.

A political cartoon by Oleh Smal’, exhibited in Lviv in Dec. 2005

Pictures of Yushchenko and Tymoshenko together taken at a press conference in September 2004 were reproduced and distributed as postcards by the Lviv regional branch of Fatherland. In 2005 this tandem inspired Alexander Roytburt to create a series of paintings depicting Tymoshenko and Yushchenko dancing several romantic ball-dances together. The appearance of Yushchenko in portraits wearing a wraparound plait à la Tymoshenko (e.g., a painting[86] and photo-collage[87]) testifies to the monolithic public perception of the two personages.

‘I love Yu’ the painting by Natalia Kolumbet; reproduced on www.oboz.com

Of course, some prefer Tymoshenko to be a pretty doll with a rather decorative function in an old boys’ game, namely politics. Evidence of such an attitude is the unbelievably high prices paid by a male money-bags for doll-like reproduction of Tymoshenko in March 2006 at a charity auction carried out by the elite women’s club “Modus Vivendi,” where 13 papier-mâché replicates of Ukrainian politicians made by Ukrainian artist Iryna Kirishyna quickly sold out.[88] The “Yulia” doll, which resembled her prototype in detail, was purchased for the highest price: $ 70 000![89] The new owner of the Yulia doll was thrilled because, as he stated, “I can hold Yulia in my hands now.”[90] This “doll” event was so successful that another charity auction of dolls took place a few months later. At it, Ukrainian politicians and other celebrities designed clothing and dressed up the Barbie dolls with their own hands. As one would expect, the Barbie Yulia was again the most expensive. It was purchased for 19 000 Euro.[91]

The doll copies of Yulia Tymoshenko sold out by auctions in Mar. and Jul. 2006

In such a context a logical question emerges: if a doll of Tymoshenko can demand such a price, how much would high-ranking men pay to handle the original?

It seems that the destiny of this prominent woman is to remain a step behind a man. Some analysts prefer to regard this as a kind of political tactic, something she first tried during the parliamentary election of 1998 when she gave first place in the party’s list to Lazarenko. Thus she let him to run out of his political, moral and financial resources while saving hers for the future.[92]

A Businesswoman

It must be admitted that Tymoshenko also performs the role of businesswoman very well. She has repeatedly stressed that professionalism is a main virtue for any political leader and consistently made professionalism her aim: “I am ready to devote my professionalism to putting in good order the life of the nation,” Tymoshenko claimed in 2001,[93] repeating in 2002 “I never gave any cause for doubt in the professionalism of my doings.”[94] This trait is indispensable for a successful career for a female politician who, in addition to everything else, has to overcome conservative gender stereotypes and male chauvinism. Experts are unanimous in their opinion that Tymoshenko has been utterly efficient in every position she has occupied.

Tymoshenko often underlines that she works a great deal in order to get the best results in the shortest possible time. Therefore her private life is reduced to a minimum, and her family members lack her attention: “My family has suffered the most from my decision to become a politician. This is my cruel payment for the right to fight for my country.”[95] Her time for personal affairs is limited (she visits her personal tailor at night[96]): “Today my life consists of three elements: 16 hours of work, a short sleep, and work again,”[97] she stated at the time of her premiership. Her colleagues confirm that she is an unusually hardworking person.[98] Her hard work (including that aimed at the creation of her political image) has helped her attain international recognition. For Tymoshenko’s achievements in 2005, Forbes rated her among the most influential female politicians (in third place on a list of a hundred).[99] In 2005 she gained a range of international awards.[100] Even her political opponents cannot deny her expertise.[101]

A Feminine Feminist?

Feminine strategies in politics are hardly a new invention, but Yulia Tymoshenko performs them very successfully and in practically a pure form. The hyper-feminine style of her appearance is meant, first of all, for the traditionally male component of her surroundings. It works like a sugar pill, helping men to swallow all of her tough statements and decisions. A paradigmatic example of such an effect was the situation of Tymoshenko’s appointment to the post of Prime Minister. As the majority of observers noted, she surpassed the utmost of expectations in voting, and there was great speculation about the role her overly feminine dress had played in it.[102]

The professionals in the fashion industry have also expressed praise for Tymoshenko’s ability to remain a woman (at least outwardly) in such a highly masculine sphere as politics. Psychologists see her as a person guided by intuition, which enabled her to sense when to become more feminine.[103] One can easily notice how the measure of femininity changes depending on the situation: her speech during a session of government is rather tough – her voice with metallic notes, an imperturbable expression on her face, whereas during a personal TV interview or public meeting she speaks and smiles softly, and uses politically correct and emotional turns of speech.

As Orysia Kulick has remarked, ‘The fact that Yulia Tymoshenko feels the need to provide evidence of her femininity on her website with photographs of her serving food, gardening, and doing housework is a sign that she is either catering to an audience that expects such behavior from her or that these ideas are so imbedded in Ukrainian society that Tymoshenko expects this from herself.”[104] In one interview she regretted not properly fulfilling her female role: “My husband is the most patient man in the world. Currently I am not able to create for him a tranquil family life as any wife could and has to create for her husband... [Once] I was a very good housewife – [then] I merely had no other option. I was always knitting, sewing something...”[105] In 2005 she confessed that she “always feels happiest while with the family.”[106]

The posters of the BYuTy parliamentary electoral campaign, Mar. 2006

However, Tymoshenko’s femininity is multifaceted. Despite the fact that she is not young girl anymore, Tymoshenko is ready to appear as one in order to enlist support. Some posters in her 2006 electoral campaign featured Tymoshenko riding a stylish motorcycle and standing by a painted wall with a spray-can in hand. These portrayals evoke an obvious association with youth subcultures (bikers and graffiti-writers), ascribing to Tymoshenko such characteristics as informality and open-mindedness, which are highly valued among youthful voters.

It would be unfair to regard Tymoshenko as blind in terms of gender issues. Some of her statements testify to her awareness of gender inequality at least in the political realm: “Men accept defeat from other men, but they hate to lose to women. So they fight women harder than men. I am the best example of that.”[107] In general, Tymoshenko regards women as more efficient and more moral politicians: “Historically female governors have provoked far fewer complaints than men; the latter defiled world history with wars, violence and betrayals.”[108] In only one of Tymoshenko’s interviews (namely that conducted by Liudmyla Taran, a feminist journalist) has she revealed her reflections on gender issues in a global perspective.[109] This rare avowal deserves to be quoted here:

The previous stage of the development of civilization has created a certain image of man, since society first needed physical muscular force. Over a long period men determined the human race’s destiny... Over millennia men implemented their worldview and ideas. It resulted in the obvious danger of civilization’s self-destruction. Men have used their chance while exploiting women’s energy in their affairs, keeping women in secondary roles...

As civilization has developed, there is no more need in men’s physical strength, so women have come to the fore... Today when world injustice has transgressed all possible limits, a women’s vocation is to bring some harmony to it... Women have to assume power at all levels... The task is to build the world on the principles of harmony and justice... Men will violently resist the women’s movement, so women have to rely on their own strength. No illusions! Women have to help each other and to develop solidarity. We have to overcome the barriers which mentally separate us... Women [should start] supporting worthy female candidates who run for Parliament or for positions in local government...

After such claims one may define Tymoshenko as a feminist, especially taking into consideration her lifestyle. But Tymoshenko herself would never admit to such a definition. Many times she has publicly repudiated associations with women’s (let alone feminist) movements, and this despite the fact that when she was imprisoned in 2001 some women’s organizations publicly supported her. Her call for women’s solidarity would seem to be very hollow, or another role performed upon request. Tymoshenko does not regard herself as a representative of women’s interests in politics. The parliamentary fraction of her parties’ bloc BYuTy voted against a bill for a women’s quota in Parliament in late 2003. It did not support the first reading of a bill on gender equality in January 2005 either.[110]

Tymoshenko seems to have no idea (at least until recently) about the goals and objectives of the women’s movement; nor does she seem to understand the meaning of International Women’s Day (March 8th). Annually she publishes congratulations on this occasion full of stereotypical perception of women’s roles – just as her male colleagues usually do. One such message is very eloquent in this sense:

Spring gives us a holiday of tenderness and love. The first flowers open the way to beauty, awaking the most sentimental feelings and new hopes. Woman’s beauty blossoms on this holiday. My dear, darling mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters! Congratulations on the occasion of this wonderful day of beauty and love...[111]

On the one hand, Tymoshenko is aware that “successful self-fulfilment in politics is possible only for women who do not comply with the Ukrainian stereotype of Berehynia, namely a woman-mother in an embroidered chemise singing lullabies.”[112] On the other hand, she displays her virtuosity in handling the variety of stereotypical images of femininity. Is this not a part she deliberately plays in a great performance, namely “Ukrainian politics”? Is this not necessary mimicry in a society with very traditional expectations about gender roles? Indeed, it seems to me that Tymoshenko is just pretending to be a stereotypical woman. She wears a range of tried-and-true feminine camouflage and uses her female “armor” to neutralize rivals, to capture enemies and to recruit allies. How far can she go in this regard? One can only hope that Tymoshenko’s feminist awareness will attain maturity before her feminine tactics run out of resources.

“Feminism is a quite good instrument to call things by their proper name,” Solomea Pavlychko, the famous pioneer of feminist thought in Ukraine, stated in an interview in 1998.[113] “I try to call things by their proper name,”[114] Yulia Tymoshenko concluded in her interview with a feminist journalist in 2002. Perhaps it was not a random coincidence, but rather an intuitive, spontaneous or unconscious discursive coherence of feminist thought in two outstanding women.

Summary

During the 1990s two ideologies impacted public discourse in Ukraine: formerly forbidden Ukrainian nationalism and formerly unknown consumer culture. These two have generated and helped two corresponding models of femininity for Ukrainian women (Berehynia and Barbie) to take root. Monitoring the political career of the most prominent Ukrainian female politician, Yulia Tymoshenko, has revealed some quite remarkable changes in her political image, especially in her appearance and rhetoric, which correspond with different stages of Tymoshenko’s ascent up to the summit of Ukrainian politics. This paper has explored a range of representations of Tymoshenko, including the photo album on her personal website, as well as other visual materials like posters, flyers, paintings, etc., her verbal messages (public speeches, interviews, etc.) as well as a number of mass media publications about her, in order to reveal how Tymoshenko has constructed and used stereotypical women’s images (including such core elements as Mother of the Nation, National Heroine, Victim/Martyr, Faithful Christian, Fashionable Lady, Sexy Woman, and Businesswoman). Both the opinions of Tymoshenko’s followers and the reactions of her opponents have been examined. The clash and confusion of feminist and feminine modes in Tymoshenko’s political strategies have been noted as well.

Note on the author

Oksana Kis, historian and ethnographer, is a research fellow at the Institute of Ethnology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Lviv; she is also a Co-Director of the Lviv Research Center “Women and Society” (NGO). Since 1994 she has been studying Ukrainian peasant women from historical and anthropological perspectives. Her current academic interests focus on Ukrainian women’s oral history as she is carrying out a research project on “Twentieth-Century Ukraine in Women’s Memories,” exploring women’s everyday lives, views, social identities and practices in (post)socialist Ukraine through the analysis of women’s autobiographies. As a visiting professor, she teaches optional courses on women’s and gender issues at Lviv National University and the Ukrainian Catholic University. She co-edited special issues of the independent cultural magazine Ji on Gender Studies (2000, #17) and Femininity and Masculinity (2003, #27), as well as the anthology Approaching Gender: History, Culture, and Society (Lviv, 2003) and a special issue of the academic journal Ukraina Moderna on oral history (2007, vol. 11). E-mail address: oksana.kis@mail.ru

Notes

[1] The author witnessed this event.

[2] All translations, from both Ukrainian and Russian, are by the author.

[3] It’s very remarkable that the Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko spent almost half the amount on its electoral campaign and gained almost double the votes that Yuschenko’s parties’ bloc Nasha Ukraina did.

[4] Certainly other models of femininity exist in Ukraine as well, such as the businesswoman and the feminist, but they are rather concealed in Ukrainian public discourse. For a discussion of the promotion of Berehynia and Barbie images in academic, public and political discourses, see Oksana Kis, “Choosing without Choice: Predominant Models of Femininity in Contemporary Ukraine.” Gender Transitions in Russia and Eastern Europe. Eds. Ildiko Asztalos Morell, Helen Carlback, Madeleine Hurd, Sara Rastback. Stockholm: Gondolin Publishers, 2005. 105-36.

[5] For a more comprehensive discussion of the fusion of the two images – the Christian Virgin Mary and the pagan (pseudo)goddess Berehynia – in the process of elaborating a new national model of femininity in Ukraine, see Marian Rubchak, “Christian Virgin or Pagan Goddess: Feminism versus the Eternally Feminine in Ukraine.” Women in Russia and Ukraine. Ed. Rosalind Marsh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 320.

[6] For Yulia Tymoshenko’s autobiography, see <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua>; for a detailed account of all the stages and aspects of Tymoshenko’s biography and personality, see Andriy Kokotyukha ed., Yulia. Kharkiv: Folio, 2006 (in Ukrainian); Dmitriy Popov and Ilya Milhtein, Oranzhevaya Printsessa. Zagadka Yulii Timoshenko. Moscow: Morozova Publishing, 2006 (in Russian).

[7] What is more, the groom was one year younger than the bride, which is traditionally regarded as an undesirable match.

[8] Tymoshenko started her political career in the Hromada (Community) party led by Lazarenko; he lobbied for her business interests (and protected her United Energy Systems) in the Ukrainian government.

[9] For details of her political program, see Tymoshenko’s personal website http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua.

[10] Her statements about the compulsory seizing of dozens of huge private enterprises (so-called “re-privatization”) in the spring of 2005 followed by an attempt by the government to directly regulate market prices for gasoline, meat, and sugar were the subjects of criticism in this respect.

[11] Andrey Slivka, “Bitter Orange.” The New York Times Magazine 1 Jan. 2006: 27.

[12] To track the changes in Tymoshenko’s appearance, see her extensive photo album on her personal website: http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua.

[13] In an interview for the radio station Hromadske Radio (Public Radio), given on January 24, 2003; the full transcript is published at http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/press/1096/.

[14] “Yulia Tymoshenko: Medvedchuk, Yanukovych, Pinchuk I Surkis budut pratsiuvaty v opozytsii”. 14 Oct. 2003 <http://www.glavred.com>

[15] “Pryvitannia Yulii Tymoshenko zi sviatom vesny - 8 bereznia” 6 Mar. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/first/606>

[16] “Zi sviatom, dorohi seliany!” 15 Nov. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/first/1059>

[17] “Zi sviatom vas, dorohi osvitiany!” 4 Oct. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/first/1031/>

[18] “Slovo do viruyuchykh naperedodni Velykodnia” 25 Apr. 2003 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/first/1146/>

[19] Interesting enough, Tymoshenko chose only three professions as worthy of her congratulations: the workers in the energy industry and the coal miners (when she was minister responsible for the energy sector), the schoolteachers, and the agricultural workers. All together these categories constitute a large and influential group of social power. Very likely, Tymoshenko chose them as her target groups because she regards them as an important part of the Ukrainian electorate.

[20] Tymoshenko’s enemies immediately vulgarized this new design in a very womanish way – it has been interpreted as “Yulia’s menses.”

[21] Valentyna Klymenko, “Riushi i plise – vid Hase.” Ukraina Moloda 19 Feb. 2005. <http://www.umoloda.kiev.ua/number/372/198/13435/>

[22] “A letter to the editorial board from Nadia” 27 Feb. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/publications/539/>

[23] Olena Zvarych, ”Persha Ledi Revoliutsiyi.” Ukraina Moloda 14 Dec. 2004.

[24] Joan B Landes, Visualizing the Nation. Gender, Representation, and Revolution in Eighteenth-Century France. Ithaca-London: Cornell UP, 2001. 18.

[25] Tymoshenko’s new image came in for negative as well as positive comment. The point is that such a hairstyle requires very long and thick hair, so it was quite obvious that Tymoshenko uses an extension. Her adherents were quite discontented with the theatricality of her new appearance; it also provoked public derision from her opponents. Tymoshenko tried to disprove the hearsay: during a press conference she unwove her plait in order to demonstrate that it was natural. But, as one could observe, this plait was completely different from the one usually worn.

[26] Sometimes such a braid is perceived as the symbolic representation of the backbone of Ukraine (Orysia Maria Kulick, “Yulia Tymoshenko: Image as Politics.” Women East-West #84 March/April 2005). Some people have compared Tymoshenko’s braid to that of Lesia Ukrainka, an outstanding Ukrainian poet with a strong patriotic and feminist spirit.

[27] This hairstyle was very popular throughout the USSR in the 1940s and 1950s as visual materials (films, posters, family photographs) from that time testify to.

[28] “Пришла костлявая с косой – голодный будешь и босой’, ‘Затяните пояса! Экономике – коса!”

[29] Korespondent September 2005.

[30] “Здесь делают прививки от оранжевой чумы. Признаки болезни: неадекватная жестикуляция, хочеться всегда врать, хочеться стать истинным украинцем-националистом, хочется одеть косу.”

[31] Bohdan Mykhaliunio, “Spadok z hlybokym korinniam.” Nahsa Bat’kivshchyna #1 August 2005: 14.

[32] Princess Olga (912-969) was the most famous woman in ancient Ukrainian history and is known as the first Christian and a wise leader of Kyiv Russ.

[33]“Everything in this short and slender woman testifies to her political foresight, analytical mind, sense of responsibility for the Ukrainian people’s destiny, exceptional management capacity, strong will, disdain for dangers in the name of the highest goals, purposefulness, firmness... She is so womanly, pretty and elegant, and everyday she is in the whirlpool of political events” (Derzhko, Volodymyr. “Ukraina pered vyborom: avtorytaryzm chy demokratiya.” Weekly Mist #38, Oct. 2001: 32).

[34] Boris Reitschuster, “Der eiserne Engel von Kiew.” Focus May 2005: 154-5.

[35] Nadiya Bodnar, “Zhinky i polityka.” Express 10 Feb. 2005: 11.

[36] Volodymyr Derzhko, “Ukraina pered vyborom: avtorytaryzm chy demokratiya.” Weekly Mist #38, Oct. 2001: 32.

Boris Reitschuster, “Der eiserne Engel von Kiew.” Focus May 2005: 154-5.

[38] Cited from the publication in Ukrainska Pravda 14 Jun. 2005 <http://www3.pravda.com.ua>

[39] “Прочел новость: Юлия Тимошенко – ‘украинская Жанна д’Арк’. Вопрос: когда ее будут сжигать на костре?”

[40] Yuriy Zushchyk. “Samurai in a Skirt.” Korrespondent #1 (190), Jan. 2006: 16-17; http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ykr/news/press/2480.

[41] Marian J. Rubchak, “Yulia Tymoshenko: Goddess of the Orange Revolution.” Transitions Online. 25 Jan. 2005 http://www.tol.cz/look/TOL/article.tpl?IdLanguage=1&IdPublication=4&NrIssue=100&NrSection=3&NrArticle=1337.

[42] Sergiy Rudenko, “Yulia Tymoshenko vid A do Ya” 12 Aug. 2005 <http://lustracia.in.ua> (reprinted from <www.ua.proua.com>).

[43] The newspaper Argument-Gazeta (15 Aug. 2005) printed a collage featuring Tymoshenko as a special agent holding a gun; the newspaper Express (22 Sep. 2005) published an article “Maydan 2: The Dreadful Vengeance” along with a picture portraying Tymoshenko as a samurai holding a sword; the magazine Vlast Deneg (#24, Jul. 2006) offered an article “Kabminnoe Pole” (“Cab-Minefield”) and designed for the cover a caricature where Tymoshenko is driving an armored train through the ambush of her political opponents.

[44] Yuriy Hrytsyuk, “Yulia Tymoshenko: ‘There is no power able to stop me.”’ Express 7 Jun. 2001: 4.

[45] Tymish Koval’chuk, Ternovy vinok Yulii Tymoshenko. Lutsk, 2002.

[46] Yuriy Rogoza, Nevykonane zamovlennia. Kyiv, 2001; this novel has been reprinted several times.

[47] Yuriy Rogoza, Vbyty Yiuliu. Kharkiv: Folio, 2006.

[48] See the comment of Volodymyr Kulyk, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Political and Ethnic Studies at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in: Andrey Slivka, “Bitter Orange.” The New York Times Magazine. 1 Jan. 2006: 29.

[49] Serhiy Rakhmanin and Yulia Mostova. “Ukraina partiyna. Chastyna 3. “Blok Yulii Tymoshenko” Dzerkalo Tyzhnia. #7 (382) 23 Feb. 2002 <http://www.zn.kiev.ua>

[50] Roksana Hedeon, “Yulia Tymoshenko: “Kuchma feels that I am his political death. And he is right!”’ Silski Visti 9 Sep. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/interview/1038/>

[51] ”Tymoshenko zminyt ikonografiyu.” Tablo ID 16 Mar. 2007 http://tabloid.com.ua/news/2007/3/15/1400.htm

[52] Marian J. Rubchak, “Yulia Tymoshenko: Goddess of the Orange Revolution.” Transitions Online 25 Jan. 2005 <http://www.tol.cz/look/TOL/article.tpl?IdLanguage=1&IdPublication=4&NrIssue=100&NrSection=3&NrArticle=13378>

[53] “Presa v zakhvati vid ‘ikony pomaranchevoyi revoliutsiyi’, ‘slovyanskoyi madonny’ ta ‘pani z kosoyu’” (‘Media are delighted by "the icon of orange revolution’, “Slavic Madonna” and “Lady with Plait”). Ukrainska Pravda 14 Jun. 2005 <http://www3.pravda.com.ua>

[54] For example, during the 2004 presidential campaign the mass media gave a great deal of coverage to Victor Yanukovych, who declared himself to have been blessed by old monks during his pilgrimage to sacred Christian places; for his part, Victor Yushchenko went to his native village to confess and receive the Eucharist and blessing from a local priest.

[55] The interview for the radio station Radio Svoboda took place on 27 Dec. 2003. See the full transcript <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/interview/1314/>

[56] Sergiy Rudenko, “Yulia Tymoshenko vid A do Ya” 12 Aug. 2005 <http://lustracia.in.ua>

[57] Liumyla Taran, “Vid filosofii imeni – do filosofii zhyttia.” Slovo Prosvity 4 Jan. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua>

[58] Tymish Koval’chuk, Ternovy vinok Yulii Tymoshenko. Lutsk, 2002: 27.

[59] Published on Tymoshenko’s personal website <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/first/>

[60] “Tymoshenko: krasoyu chy stylem?” Ukrayinska Pravda 8 Feb. 2005 <www. pravda.com.ua>

[61] Marian Rubchak, “Christian Virgin or Pagan Goddess: Feminism versus the Eternally Feminine in Ukraine.” Women in Russia and Ukraine. Ed. Rosalind Marsh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 315-30.

[62] “Красота спасет мир!” – the Russian noun mir means both “world” and “peace.”

[63] See the photo signed “Yulia Tymoshenko – A Revolutionary Joan of Arc” in L. Ardzhakovska and P. Didula, eds. Revolutsia dukha (Revolution of Spirit). Lviv: Svichado, 2005: 176.

[64] Express. 27 Jan. 2005: 3.

[65] See the short overview of those changes in: “Tymoshenko: krasoyu chy stylem?” Ukrayinska Pravda 8 Feb. 2005 <www.pravda.com.ua>

[66] To trace these transformations, see Tymoshenko’s photo album on her personal website <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua>

[67] Interview for the radio station Hromadske Radio 24 Jan. 2003; the full transcript (in Ukrainian) is published at <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/press/1096/>

[68] This statement was made in a report devoted to Tymoshenko’s clothing. It was televised on the evening newsprogram ТСН on the national TV channel “1+1” on 11 Feb. 2005; the full transcript and video are available at <http://www.1plus1.kiev.ua/news/>

[69] Valentyna Klymenko, “Rushi i plise – vid Hase.” Ukraina Moloda #032, 19 Feb. 2005. <http://www.umoloda.kiev.ua/number/372/198/13435/>

[70] Nadia Bodnar, “New Record of Yulia Tymoshenko” Express, 7 Jul. 2005: 10-11.

[71] Shandor Skhidniak, “Yuliada.” Narodnaya Opozitsiya # 3(10), Apr. 2005: 8; translated from the Russian by Oksana Kis.

[72] “Yushchenko i Tymoshenko – sex symvoly.” Argument Gazette #31, 3 Aug. 2005: 2.

[73] A recent survey of Ukrainians shows that “men name Yulia Tymoshenko the sexiest female politician almost without hesitation” (according to the data published by the internet magazine Tabloid 5 June 2006 <http://tabloid.com.ua/news/2006/6/5/569.htm>

[74] Statement made during Tymoshenko’s internet-conference in the editorial office of Ukrainska Pravda, as reported by Ukrainska Pravda: “Tymoshenko zyavylasia na obkladyntsi ELLE.” 18 Apr. 2005 <www.pravda.com.ua>

[75] Ukrainian newspapers were full of the articles like “A Woman of Colorful Dreams: The Playboy Shine of the Female Prime Minister.” Weekly Mist # 23, 16 Jun. 2005

[76] The movie first night took place on the 24th of September 2005 in Moscow; for details see <http://www.from-ua.com/news/4335649f03117/>

[77] “Will the Erotic about Tymoshenko Raise her Rating?” <http://www.from-ua.com/news/433adfc2e65e/>

[78] This happened in October 2005 in the city of Kirovograd; for details see: Harmash, Volodymyr. “Milyony oholenykh Yul.” Vysoky Zamok # 191, 20 Oct. 2005: 2 <www.wz.lviv.ua>

[79] For the photo of the painting and the author’s comments see: Skriabikov, Anton. “Yuliu razdeli dogola.” Komsomolskaya Pravda – Ukraina. # 209, 4 Nov. 2006: 1-2.

[80] Orest Sokhara, a journalist with the magazine PIK (Politics and Culture), first called Tymoshenko Lady Yu.

[81] Nadia Bodnar, “New record of Yulia Tymoshenko.” Express 7 Jul. 2005: 10-11.

[82] “Yuschenko I Tymoshenko – sex-symvoly.” Argument Gazeta #31, 3 Aug. 2005: 2.

[83] Yulia Lymar, “V tsentre vnimaniya.” ELLE Ukraine May 2005: 64-8.

[84] Alexandr Kochetkov, “Tymoshenko chy Yuschenko: za koho holosuvaty?” Express 18 Oct. 2001: 16.

[85] Olena Zvarych, “Persha ledi revoliutsii.” Ukraina Moloda 14 Dec. 2005.

[86] Natalia Kolumbet’s painting entitled “I love Yu”, 2005.

[87] One of them named “VitYulia Yumoshenko” was published in the newspaper Express Gazeta # № 27, June 2006.

[88] For details and pictures, see Olesia Petrenko, “Kak v Kiyeve politikov prodavali.” Moskovskiy Komsomolets v Ukraine . 29 Mar. 2006: 9.

[89] Compared to the Yushchenko doll, which cost $14 000, let alone others which sold for even less.

[90] There were rumors afterwards suggesting that Yulia herself had arranged this purchase as a part of her PR campaign.

[91] For details and pictures, see “Naydorozhcha lial’ka Yulia.” Weekly Mist. #28, 27 Jul. 2006: 19; “Kukla Yulia, kukla Katia.” Korrespondent. # 29, July 2006: 46.

[92] “Center of Rating Studies Elite-Profi about Yulia Tymoshenko” 27 Nov. 2001 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/>

[93] Ukrainska Pravda 26 Dec. 2001.

[94] Roxana Gedeon, “Yulia Tymoshenko: ‘Kuchma vidchuvaje, shcho ya – yoho politychna zahybel. I pravylno vidchuvaye’” Silski Visti. 9 Oct. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/interview/1038/>

[95] Sergiy Rudenko, “Yulia Tymoshenko vid A do Ya” 12 Aug. 2005 <http://lustracia.in.ua>

[96] Valentyna Klymenko, “Rushi i plise – vid Hase.” Ukraina Moloda #32, 19 Feb. 2005. <http://www.umoloda.kiev.ua/number/372/198/13435/>

[97] Yulia Lymar, “V tsentre vnimaniya.” ELLE Ukraine May 2005: 67.

[98] Ivan Serhiyenko, “Enerhetychni reformy ochyma ocevydtsia: yak tse bulo?” Vechirni Visti #048(744), 29 Mar. 2002: 4.

[99] FORBES <http://www.forbes.com/women/>

[100] See the complete list on Tymoshenkos’ personal website <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/>

[101] A special issue of the weekly magazine Korrespondent (#1, 12 Jan. 2006) came out on “The Personality of the Year – Yulia Tymoshenko”.

[102] This event took place on February 4, 2005; Tymoshenko gained a record number of votes: 373 out of 450.

[103] These statements were made in the reportage devoted to Tymoshenko’s clothing televised in evening news ТСН on national TV channel 1+1 11 Feb. 2005; see the transcript and video ,http://www.1plus1.kiev.ua/news/>

[104]Orysia Maria Kulick, “Women of the Orange Revolution.” Women East-West. #83 (2005): 12-13.

[105] Sergiy Rudenko, “Yulia Tymoshenko vid A do Ya.” 12 Aug. 2005 <http://lustracia.in.ua>

[106] Interview for the TV program Chas Pik (Peak Time) televised on TV channel the 5th Canal 7 Aug. 2005

[107] “Kyivsky zaliznyy anhel" 1 Feb. 2005 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua/ukr/news/publications/1593/>

[108] “Yulia Tymoshenko: “Medvedchuk, Yanukovych, Pinchuk and Surkis will be in opposition”’ 14 October 2003 <http://www.glavred.com>

[109] Liumyla Taran, ”Vid filosofi imeni – do filosofii zhyttia.” Slovo Prosvity 4 Jan. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua>

[110] This bill passed several parliamentary readings and was approved as The Law of Ukraine on Equal Rights and Opportunities of Men and Women, which came into force on January 1, 2006.

[111] Vechirni Visti 6 Mar. 2002.

[112] Liumyla Taran, ”Vid filosofi imeni – do filosofii zhyttia.” Slovo Prosvity 4 Jan. 2002 <http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua>

[113] Liumyla Tarnashynska, “Solomea Pavlychko: ‘Feminism – nepohany instrumeny, schob nazvaty rechi svoyimy imenamy.”’Day 13 Jun. 1998: 1, 6.

[114] Liumyla

Taran, ”Vid filosofi imeni – do filosofii zhyttia.”

Slovo Prosvity 4 Jan. 2002 http://www.tymoshenko.com.ua