by Jarrett Robert Rose, York University, Canada

(AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

In 2016, I landed the most challenging job of my life: Teaching at a juvenile detention facility.

Now it’s not what you might immediately think — I wasn’t unqualified.

In both the city I was born, Long Beach, Calif., and in San Diego where I went to graduate school at San Diego State University, I’d taught and studied under-served and marginalized populations.

Yet inside a newly created trauma-reduction unit, I was tasked with providing a general humanities curriculum to psychologically distressed, incarcerated youth — a population, and setting, you can’t simply “prepare” for.

It was this experience that forced me to realize the importance of safety and security — both physical and emotional — on children’s mental health.

My research is on the social determinants of mental health, and I study the correlation between intergenerational trauma, mental health and incarceration.

I’ve learned that nurturing parents, and a safe, stress-free environment are both crucial for healthy development and indicative of a lower probability of committing crime.

Social class and environment also contribute substantially to mental health: Families of low socio-economic status are both more likely to experience adversity and stress, and have less resources for coping.

We don’t choose the lives we’re born into

As a sociologist, I don’t believe in the ideology of “meritocracy.”

We do not get to choose the neighbourhood we grow up in. Racism and poverty have an impact on our opportunities.

We do not get to choose the psychological makeup of our family (such as past abuse or addiction issues), nor their educational background or socio-economic status.

We don’t get to decide the amount of love and affection — or hatred and violence — we’re exposed to. We don’t get to choose the opportunities — or misfortunes — that are afforded to us.

So inside that detention facility, my question was never: “What did this individual do?” It was, rather: “What has this population been exposed to?”

The answer shouldn’t shock you. What I realized at the end of my teaching term was, sadly, pretty straightforward: Not a single student I encountered was given the opportunity to live a healthy, stable, peaceful life.

Instead, there was one commonality, one characteristic thread sewn into each of their lives: Trauma.

PTSD takes a toll

Recent social science literature on the social determinants of mental health suggests detrimental childhood experiences — such as parent-child separation, for example — predict increased levels of developmental/learning disabilities, anxiety, depression and drug addiction.

Post-traumatic stress disorder — a likely outcome of such experiences — can severely threaten psychological and physical health for a lifetime, and both the victim and those closest to them are at risk.

When parents are absent from a child’s most important developmental stage, children regularly confront difficulties cultivating the necessary emotional skills needed to form lasting, intimate bonds.

And when those problems aren’t resolved in adulthood, patterns of inter-generational trauma can be established.

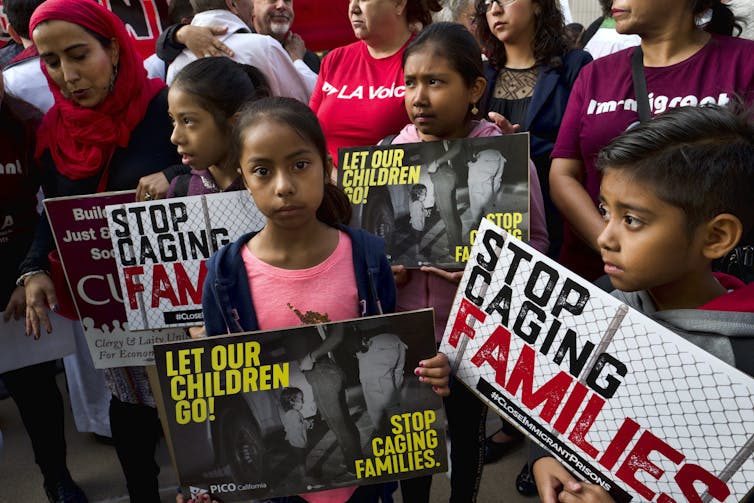

You’ve seen the photos, heard the cries, and read the heartbreaking stories — more than 2,300 children and counting have been taken from their parents.

In some cases, families have been separated for up to eight months, and in others, more than 300 youth may have become “lost” in the bureaucratic labyrinth of federal agencies — all of this in addition to the terrible conditions that forced them to leave their home countries in the first place.

Allegations of abuse, including being forcibly drugged and assaulted, have also begun to emerge.

One 15-year-old Honduran boy fled one facility, and is reportedly undertaking a dangerous attempt to make his way back to his country on his own.

How any person, parent or political administration could have initiated, supported and justified this policy, without the attendant horror and rage that fills most of us, is beyond comprehension.

Though U.S. President Donald Trump has now done a supposed about-face on his policy of using traumatized children as bargaining chips in his political games, large numbers of children may never find their parents. The administration has so far not committed to reuniting these children with their parents.

Trump may believe he has contained the uproar following the widespread public and media backlash, but I assure you, the damage has already been done — and an entire generation, in the U.S., Central America and abroad, will absorb the consequences.

Jarrett Robert Rose, Teaching Associate and Ph.D. Student, York University, Canada

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.