Conducting Remote Research Interviews to Explore Student Learning

By Ameera Ali

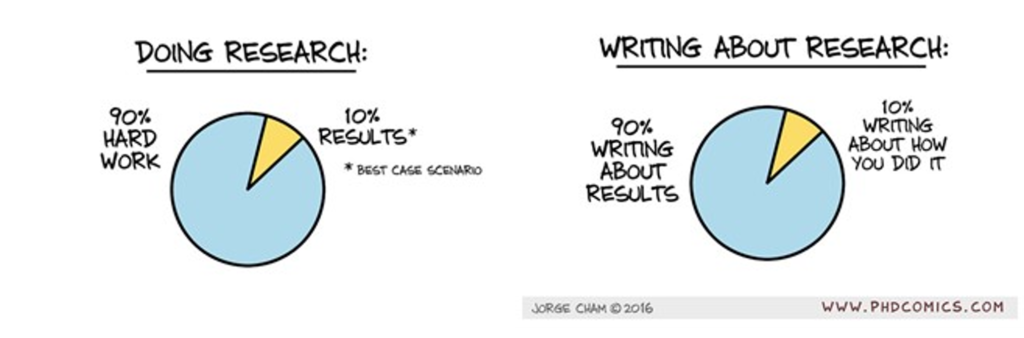

For anyone who is familiar with conducting research, the above graphic may seem relatable at times when one reflects on the process of research. In this blog post, I briefly touch upon one of the more under-emphasized areas of the above image: the ‘how’ of research. More specifically, I share some reflections on my experiences of conducting remote research with students. The research I reflect on in this blog pertains to qualitative student-centred research which involved me conducting individual interviews with post-secondary students to explore their experiences of university teaching and learning. Below, I offer a few quick tips that you may wish to consider in your own remote student-centred research. Each tip is followed by a brief account from my own experience, contextualizing the information further. These tips are not meant to be prescriptive, but rather, they are meant to inspire reflection and I am hopeful that this post may be useful for those already conducting, thinking about conducting, or simply reflecting on conducting remote research with students.

Participant Recruitment

Tip: Recruit by visiting students in their virtual classrooms (when possible and permitted)

Sending out recruitment emails to student listservs (with permission) is a great way to gauge and gather interested participants for student-centred research. In addition to this, I have also learned that visiting students in their actual classrooms can add a nice personal touch to the recruitment process. In my former non-remote research, I recruited student participants by formally going into various classrooms, introducing myself, providing an overview of my research, offering opportunities for questions, and passing around a sign-up sheet. This process became enhanced with my remote research as it was easier for me to ‘enter’ an increased number of classrooms (via Zoom); easier for me to ensure recruitment materials were made available to all students (I was able to post my research flyer, contact information, and virtual sign-up calendar into the chat for all to access); easier for me to connect with interested students directly (I was able to answer private questions through Zoom chat thereby being less invasive and disruptive to the instructor’s lecture); and easier for students to express interest confidentially (there was no sign-up sheet circulated, students were simply able to send me a private message and/or their contact information). This also helped me to establish a sense of rapport with participants before the research took place. Although these opportunities may not always be feasible, try to seek out ways to connect directly with participants during the recruitment process whenever possible to ‘humanize’ the experience.

Conducting the Interviews

Tip: Use the virtual experience to ensure increased access and equity

In my non-remote research, participants and I met in my office to conduct the interviews. This was a positive experience all around, however after conducting virtual interviews with students over Zoom, I realized the ways that these can enhance access and equity for participants. First, anonymity was significantly enhanced as there was no risk of others seeing a participant entering or leaving my office. If the nature of your research topic is sensitive, anonymity for student participants is especially paramount. Taking anonymity one step further, virtual interviews via Zoom allowed students to remain anonymous even in focus group interviews as participants could rename themselves, leave their videos off, and participate solely via chat if they so wished. The option of leaving their videos off and utilizing the chat, also increased access and equity for participants, as this allows for researchers to reach more participants and invite them to participate in a way that is most accessible for them. I was also able to post interview questions directly into the chat, making it easier for both myself and the participant to follow along, further enhancing access to the experience. Moreover, when considering access and equity, enabling the live transcript in Zoom not only allowed me to review the transcript afterwards, but it also, and perhaps more importantly, allowed for participants to have access to a live speech-to-text transcription during the interview. Although not always accurate and not akin to Closed Captioning (CC), live transcriptions can increase access for participants (and researchers) significantly.

Contextual Factors with Remote Interviewing

Tip: Be mindful of the ways a virtual interview arrangement may impact your participants

Although a virtual interview can offer many advantages for participants (e.g. increased accessibility in arranging an interview space), it can also be a hindrance if participants are already spending a significant amount of time on a device as it is. At the time I conducted my interviews, my participants were entirely immersed in remote learning, often spending many hours (both daily and weekly) in Zoom classrooms and on the computer. Thus, despite the time that may be saved from travelling to and from an on-campus research interview, participants are likely engaging in many other virtual meetings regularly and may feel quite ‘Zoomed out’ themselves. As such, it is critical to be mindful of issues such as ‘Zoom fatigue’, and ensure that the anticipated interview duration is communicated to participants before having them agree to participate in the interview. In my case, I strove to keep the interviews within 60 minutes (unless participants willingly expressed wanting to speak longer), and I offered opportunities for breaks if participants needed a moment to think or turn off their video for a little while. I learned that this is also important to consider for yourself as a researcher as well. I made the mistake of scheduling multiple back-to-back Zoom interviews each day, which at times, made me feel like a zombie at the end of the day (or as I like to say, a ‘Zoombie’). As such, scheduling interviews in a way that is manageable for yourself is also salient to ensure that you are refreshed and engaged throughout the interview process. Moreover, since virtual interviews also allow us to reach students in different time zones, ensuring the timings are convenient for both participant and researcher is key.

A Few Other Ethical Considerations:

In addition to the reflections provided above, I would like to touch on a few remaining ethical considerations involved in conducting remote interviews with student participants:

- A large benefit of conducting remote interviews (via Zoom, in particular), is the ability to record the interview directly from your device. This is especially appealing as the recordings will automatically be stored to your device, there is decreased shuffling and background noise compared to an in-person recording where one may need to move the microphone back and forth between participant and researcher, and the quality of the recording itself tends to be much clearer. This being said, however, some participants may be hesitant to turn on their video if the interview is being recorded. To ensure participants feel as comfortable as possible throughout the interview process, you may choose to record audio only if a video recording is not necessary.

- Speaking further to the notion of interview recordings is a point that was brought to my attention by a few participants themselves. In virtual focus groups, some participants may worry that the interview may be recorded from another participant’s device (e.g. as a screen recording) without other participants’ knowledge. Although we always assume the best of participants, this concern is an important one; and admittedly, one that I had not considered until it was brought to my attention. Although as researchers we cannot control for uncontrollable dynamics, we can ensure that we explain all potential risks when obtaining informed consent from participants, always underscore our expectations (e.g. confidentiality, non-permitted screen recordings, etc.), emphasize that participation is voluntary, and reiterate options for anonymous participation (i.e. turning video off, renaming, and utilizing the chat). Establishing focus group community agreements with each focus group can also enhance feelings of safety and agency for participants throughout the interview.

- In an in-person interview it may be easier to provide refreshments, snacks and any other offerings to create a sense of connection with participants and to expression an appreciation for their time. This can be challenging with remote interviews as there is no non-virtual interaction. As such, in addition to creating a welcome interview space, offering an incentive can go a long way for student participants. At the time my research was conducted, many students expressed that they had been experiencing employment insecurity, having many non-academic demands and responsibilities, and an overall feeling of uncertainty. In my case I was fortunately able to offer a small incentive to each participant in appreciation of their time, however if this is not possible it is always good practice to provide them with something they can ‘take away’ from the interview, such as a relevant resource.

- Considering power dynamics when conducting interviews with student participants is critical whether the interviews are in a remote or non-remote environment. In a remote interview, power dynamics can be minimized as participantschoose their own setting on their end, which can provide them with a sense of agency in the research experience and increase feelings of safety. It is equally important as a researcher to engage in researcher reflexivity and be cognizant of the ways that your virtual environment may influence a participant’s experience. It is good practice to be mindful of the ways your appearance, background, and general surroundings may be received by a student participant. In my case, I strove to minimize any perceived power imbalances as much as possible and opted for non-professional clothing, a neutral background, and a quiet, private space in hopes of creating a welcoming and comfortable interview environment for my participants.

Given how diverse and varied experiences with remote research can be, this post certainly only scratches the surface on the topic, but I do hope that these tips and reflections provide you with some insights into what the process of conducting remote interviews with students can entail. Your experience may be very similar or very different but in any case student-centred research can be a highly fulfilling experience. I invite you to reflect on your own and perhaps consider how you may contribute to discussions on the ‘how’ of remote research from your own experiences. Happy researching!

About the Author

Ameera Ali is an Educational Developer in York University’s Teaching Commons whose work is focused around issues of equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in teaching and learning in higher education.