By Ashley Goodfellow Craig

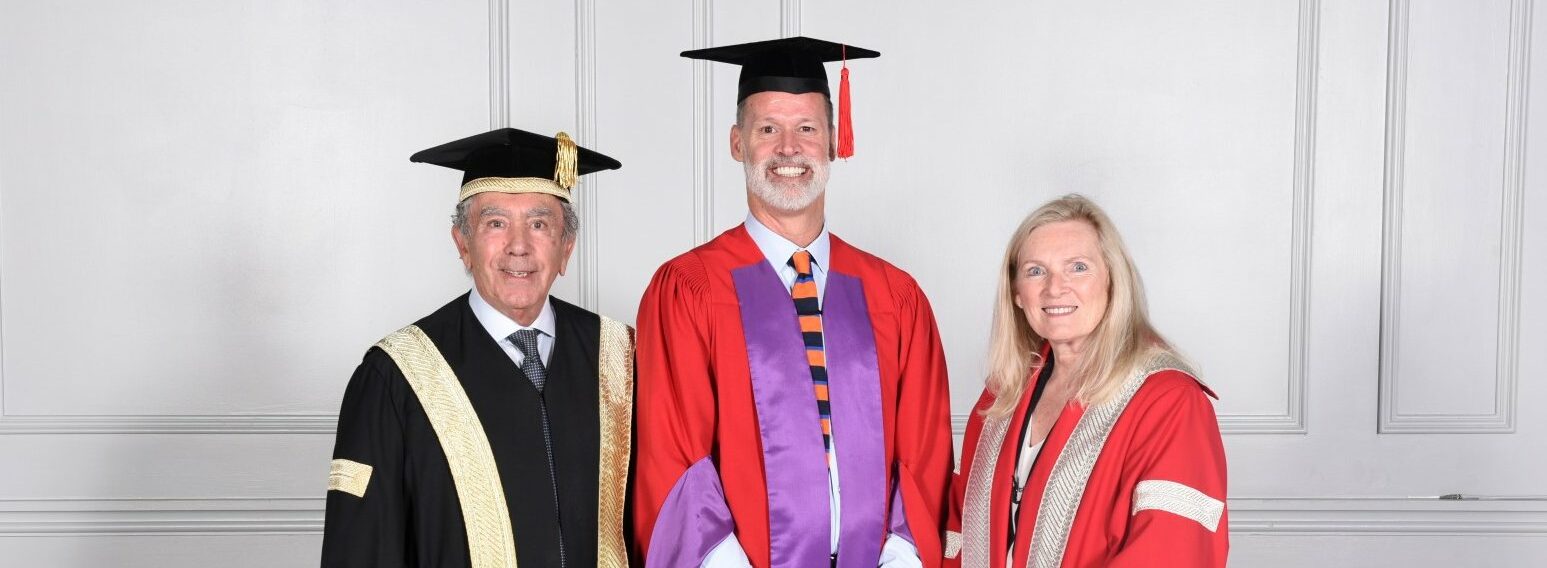

Olympic champion, human rights activist and inclusion advocate Mark Tewksbury received an honorary doctor of laws during York University’s convocation ceremony for graduands from the Faculty of Health.

The ceremony, held Oct. 12 at 10:30 a.m., was the first of eight for York’s 2022 Fall Convocation.

An Olympic champion winning bronze, silver and gold medals for swimming for Canada, Tewksbury’s success as a professional athlete launched him into a post-Olympic career focused on human rights, inclusion and equity.

In 1998, Tewksbury became known as Canada’s first openly homosexual sports hero, and has since become a personal mentor to many athletes in the 2SLGBTQ+ community. He is also an advocate for inclusive and safe sport spaces for all, and is the co-founder of OATH, an advocacy group that holds the International Olympic Committee (IOC) accountable and pushed them to adopt a more inclusive governance structure.

In 2020, he was appointed Companion of the Order of Canada, the highest level of one of Canada’s most prestigious honours, and is a long-standing advocate for the Special Olympics.

After congratulating the Class of ’22, Tewksbury shared with graduands an inspirational message of overcoming self-doubt – something that he, despite his long list of achievements and accolades, grapples with from time to time.

“Something extraordinary happened in my life four weeks ago today, on Sept. 14,” he said, sharing in enthusiastic detail a call he received from the Privy Council Office inviting him to be part of the 19-person delegation representing Canada at the state funeral for Queen Elizabeth II.

The invitation mean pivoting quickly to accommodate the request – which, Tewksbury pointed out, is a great lesson to draw from.

“We can plan so much in life, and it’s great to have plans, but maybe the most important thing in today’s world is agility – the ability to make things happen,” he said.

And so he did, and participated alongside prime ministers, governor generals and national Indigenous leaders as part of the honours procession for the funeral. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and he had a front-row seat to history in the making.

What he didn’t prepare for upon his return to Canada, was how others would respond to his experience.

“People have asked all kinds of things about my experience, but I have to say, there’s a certain type of person … that will come up to me and say, ‘So, why you? Why did you get to represent Canada at the funeral?’”

On those occassions, Tewksbury tried to justify his invitation with a list of his achivements and attributes: he’s a Companion of the Order of Canada; he is an openly gay public figure; he is a decorated national athlete – but even those responses didn’t satisfy the query.

“He said to me, ‘Well, I guess you don’t even know why you were chosen’ and obviously, that conversation haunted me,” said Tewksbury. “How do I answer this question of ‘why me?’ – and then I had this Eureka! moment that took me back 30 years ago.”

He recalled his big breakthrough as a swimmer in the early 1990s when he placed second in the World Championships by six-one-hundredths of a second behind the gold medallist and world record holder Jeff Rouse, but eight months later finished much farther behind.

“I really felt like I was at the bottom of the world, but sometimes, I’ve learned in life, the worst moments turn out to be the best,” he said. “In hindsight, that was this situation. I noticed things I hadn’t noticed before, and I looked at the world in a different way because of this catalyctic event.”

He began working with a coach who recognized that improving technical skills would help bring Tewksbury a gold medal, but what he needed to work on most was confidence. Together they worked on all the reasons why he felt he “couldn’t beat Rouse” and faced them one-by-one.

“It changed my thinking and my belief, so that by the time I got to the Olympics and the morning of the 100m backstroke, I was a different person.” He qualified for second place for the finals that evening, and during the break before the finals he thought “Somebody has to win this race tonight. Why not me?” and he couldn’t think of a single reason why not.

“So I said it again. ‘Why not me?’ And I went out there and swam, I dropped 1.2 seconds, I out-touched him (Rouse) by six-one-hundredths of a second. So fast-forward 30 years, and how do I answer this ‘why you?’ question?”

And he reached back to his swim training and answered with “Why not me?”

“We all have doubts and fears, we compare ourselves to others at times, we question if we are good enough or if we can do something – and I think it’s healthy to do that sometimes, it keeps us humble and real, human – but we must never let those self doubts hold us back. There are way too many other people doubting us, we need our own strength to lean into, and to lean into the things that make us uniquely who we are.”

He encouraged grads to be agile and flexible; to take opportunities that arrive; to face things that might hold them back; and to take action and continue doing the work.

His final reminder: “It doesn’t matter how many titles you have, or experiences or success or degrees, there’s always going to be someone that is that kind of person that will ask ‘why you?’ and and I say ‘why not you?'”