Biography

Publications

Philosophy

Curriculum Vitae

Contact

Up in "my" tree

ca. 1966

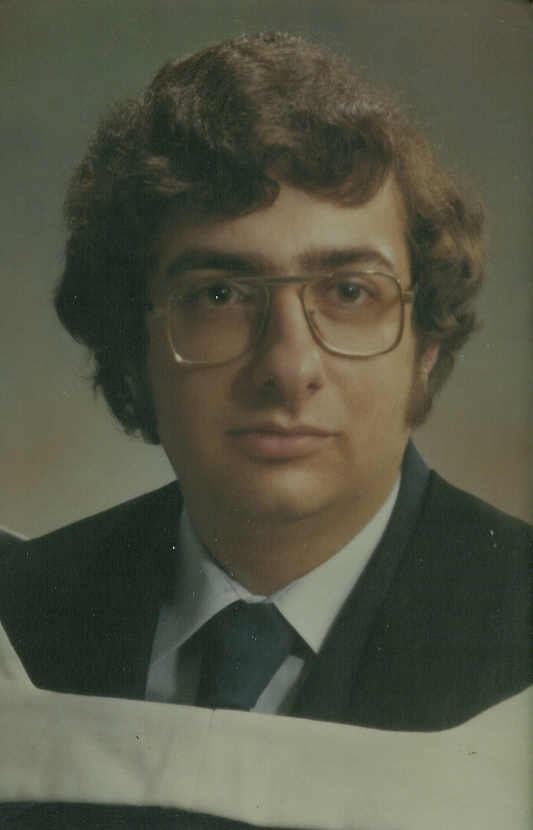

B.A. grad photo

Ph.D. convocation

June 1985

Nose to nose with a Bactrian camel

Toronto Zoo, 1990

"Out of This World" Exhibit on Canadian SF

1995

Biography

I was born in Montreal October 23, 1956. My father, Thomas, is a Holocaust survivor, having spent the war years in the Jewish ghetto in Budapest. His biological mother died not long after his birth; his second mother (whom he referred to as his "real" mother) may have died at Ravensbruck concentration camp. His father was taken away to work as a forced labourer, and disappeared. My father emigrated to Canada after the war, and was one of the last allowed to leave Hungary before the Stalinists closed the border. My mother, Freda, was born in Montreal; her father, known in our family as Zaidy, was an immigrant from somewhere in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (probably Romania), and her mother was part of a large family that had its roots in Poland.

It would be wrong to say that I became a writer at some point. I was making up stories as far back as I can remember, and couldn't fall asleep at night until I'd come up with an adventure for the recurring characters I'd created (my first "story cycle," I suppose). My parents sold Jewish New Year cards as a sideline, and I would borrow pads of order forms so that I could draw comic books on the blank backs of the forms.

I spent most of my early years in the section of Montreal known as Côte des Neiges--and the particular neighbourhood I grew up in became the setting for my Living Room stories. While the plots of those stories are entirely fictional, many of the details are authentic, notably the strange sort of education Jewish children like myself experienced. Until very recently, Quebec's education system was entirely denominational: you went to either a Protestant or Catholic school. Jews sent their kids to Protestant schools because they were English and willing to accept us. The Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal's curriculum included hymn-singing, and so classrooms made up largely, or at least substantially, of Jewish kids nevertheless rang with the sounds of "Onward, Christian Soldiers" and "Jesus Loves Me." Some of us attended afternoon Hebrew school twice a week, where we learned a little Hebrew and a lot about Jewish holidays. Most of those holidays, incidentally, celebrate our victories over oppressive gentiles; we'd hear about the triumph of Chanukah after spending Art class making Santa Claus faces out of construction paper and cotton.

I discovered science fiction in the two-shelf libraries that graced our classrooms, and I soon began devouring the adventures of Tom Swift, Jr. (and his best friend Bud) and Tom Corbett. I loved reading, and since I've always been a bit synaesthetic the words and letters in my school readers took on flavours, colours, and textures for me.

In Grade IV I had my first experience of abused authority: our teacher derived some sort of satisfaction from humiliating her students. Poor Lorne--his "crime" was that for some reason he didn't swing his arms when he walked, and Miss B. made him come up to the front of the class so she could teach him to do so. She was unhappy with the length of my nails and did something about it with a large pair of scissors--again in front of the class. She became the source of Miss Shaw in "Minorities," published in Fiddlehead in 1992. (I learned much later that not long after she taught us she spent some time in a psychiatric hospital.) What I discovered was how dangerous misused power was, although I knew plenty about it in an abstract way thanks to my father's stories. In 1968 we moved to Ville St. Laurent, a suburb of Montreal, and I had a difficult time adjusting, especially to the jungle-like nature of the schoolyard at my new school. I had my second lesson in abused authority in a confrontation with a principal who punished first and asked pertinent questions . . . never.

I lived in Montreal during a turbulent period: the excitement of Expo '67, with its promise of all things new and Modern; separatist bombings culminating in the October Crisis of 1970 (I still remember CFCF showing a picture of murdered Labour Minister Pierre Laporte while sombre music by Mozart played in the background); later on, the Olympic Games and the election of the Parti Quebecois in 1976.

More importantly for me, I began to see writing as something one could do as a profession (although not necessarily a lucrative one). I submitted stories to Fantasy and Science Fiction and other magazines, and made my first sale at the age of 17: a horror story to Amos (now Jessica Amanda) Salmonson's Magazine of Fantasy and Terror, for the princely sum of $15 plus a year's subscription. The story was later accepted for inclusion in Year's Best Horror Stories, much to my amazement then and now. Salmonson included some of his own lines in the story without my authorization, and I wasn't able to get the worst passages removed by the editor of the anthology. "Impotent fetish"??

Also, I underwent what can only be described as a spiritual crisis, as I struggled with the question of the existence and nature of God. Around the age of 16 I became an atheist, and my skepticism has had a profound effect on my themes and techniques. In fact, I think of my stories as "atheist fiction" in which characters find their most cherished beliefs and assumptions about the world exploded before their eyes. The experience of losing one's faith is stunning, provided that it is a true loss. Some people say they're atheists because they can't believe in a God who would do so many apparently cruel things--but assuming things about how God or the world should work violates the spirit (if I can use the term) of true atheism.

I attended Sir Winston Churchill High School and Vanier College C.E.G.E.P. (junior college) in St. Laurent. Around this time I discovered Canadian literature, as I sought out those who were trying to do what I wanted to do: write out of the Canadian experience. I read such masters of the Canadian short story as Alice Munro, Margaret Laurence, Clark Blaise, and Audrey Thomas, and largely stopped reading and writing science fiction, as I was more interested in--and had no time for anything but--Literature. I received my C.E.G.E.P. diploma in Languages and Literature in 1976 and enrolled in the English programme at Concordia University. At both Vanier and Concordia I took courses in Creative Writing, and had the opportunity to study with Audrey Thomas and Elizabeth Spencer at Concordia. I tried writing a mainstream story cycle, but had more success when I attempted a "Jewish" voice, and sold my first such effort (eventually) to a small literary magazine called Green's Magazine. Mostly, though, my academic work drained my available time and energy, and I wasn't very creatively productive.

I chose to do my academic work as quickly as possible, thinking my efficiency would impress future potential employers. (It hasn't.) I completed my B.A. in three years, as was normal in Quebec, then my M.A. at Concordia in one year--including a thesis on Henry Fielding--before moving to Toronto to do my Ph.D. at the University of Toronto. From the time I registered in 1980 to the time I submitted my dissertation was a mere four years; I participated in the convocation of June 1985. By then I was working on my first bibliographic project: a comprehensive bibliography of English-Canadian short stories first published between the years 1950 and 1983. My work was financed by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). You can find "The Bib" at most university and large public libraries.

After working as a teaching assistant throughout my graduate studies, I got my first "real" teaching job, as a part-time instructor at Ryerson, during the summer of 1984. I taught there occasionally during the next five years, while from 1986-1988 I worked full-time as an indexer for ECW Press's Canadian Literature Index. In 1990, I began teaching at Woodsworth College, the University of Toronto's centre for part-time and evening studies. I taught Canadian Studies in its Pre-University Programme, a course I particularly enjoyed teaching. I also began part-time work at York University, teaching science fiction at Stong College till 1993, when I started a new course I designed called "Immigrant Humour in Canada." I taught part-time till 2003, when I was given a "conversion" appointment, meaning that as of July 1 I was a full-time Assistant Professor of English and Humanities. I got tenure and promotion to Associate Professor in 2005.

During my studies I made sure to work on short stories and longer writing projects to keep myself sane. While doing my doctorate I started on my unpublished SF novel "Alshomak," my first work of science fiction in many years. I showed part of this novel to Judith Merril when she was Writer-in- Residence at the Merril Collection (then the Spaced Out Library), and it prompted her to invite me to join the workshop she had founded. The workshop never adopted an official name, but we unofficially call ourselves the Cecil Street group, as we used to meet at the Cecil Street Community Centre. The group has provided me with encouragement, invaluable advice, and valued friends. And they were patient enough to read my mainstream Living Room stories when I asked them to.

A number of my stories, both SF and mainstream, were published in the 1990s: "Ants" in Tesseracts 4, "Minorities" in Fiddlehead, "Living Room" in Short Story (University of Northern Iowa), and "Fixed" in NorthWords, among others. More recently, I have tried my hand at novellas, and "The Last of the Maccabees" appeared in Arrowdreams in 1998. Perhaps the most fun I've had as a writer, however, was doing the column "Socially Speaking" for the North York Mirror (1995-1997), in which I got to express my political views (and trash Mike Harris and his Tories) every week.

Throughout the 1990s, I continued to write short fiction and to research a historical novel on the Winnipeg General Strike. The Living Room stories appeared in book form from Boheme Press in 2001; an excerpt from the novel was published that same year in Rampike literary magazine. Another work of fiction that came out that year was a fantasy story, "The Missing Word," otherwise known as my "Jewish wizard story." It was published in the Summer issue of On Spec. I've had a couple other stories about Eliezer ben-Avraham published in the magazine since then, as part of an eight-story cycle that I hope to complete in 2013.

During the 1990s, I also kept active as a scholar, presenting papers at conferences in Canada, the United States, and Europe and publishing scholarly articles in learned journals. In 1990, I received another SSHRC grant to compile the 1988 volume of Canadian Literature Index. In 1992, Hugh Spencer and I won the contract to organize the National Library of Canada's exhibit on Canadian science fiction and fantasy, "Out of This World," which ran from May to December 1995. I also conducted interviews for the Merril Collection's newsletter, SOL Rising, wrote articles for reference books and book reviews for journals, and began work on a book-length study of Canadian SF tentatively entitled "Beyond the North." In 1995, as part of the events surrounding the opening of the National Library exhibit, Jim Botte of CanCon and Sian Reid organized the first of a planned annual series of academic conferences on Canadian SF. I gave a paper at that conference, then Jim asked me to organize future conferences; in 1997, I started a new series in Toronto, and the success of that conference gave me hope that the Academic Conference on Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy will continue for many years. For ACCSFF 2003, we were lucky enough to get Margaret Atwood as our keynote address speaker. To see what we've been up to, please visit the conference website at www.yorku.ca/accsff

In addition, I discovered the joys and, unfortunately, the sorrows

of volunteer labour. For a while I was head of the Canadian branch of a volunteer

health organization dealing with interstitial cystitis. One of my other contributions

as a volunteer was the creation in 1986 of a walkathon I called "Superwalk";

its purpose was to benefit research into Parkinson’s Disease and to honour

Zaidy, who died in 1985 partly as a result of the disease. At first I conducted

the walkathon on my own; then, in 1991, I donated the walkathon to the Parkinson

Foundation on condition they name it after my grandfather. The Harry Zwecker

Memorial Superwalk ran for two years, then the Foundation changed its name--contrary

to our agreement and over my objections—to Superwalk for Parkinson’s. That

ended my association with the organization, or so I thought. I recently wrote

to the organization to tell them who I was and how the walkathon began; they

contacted me and invited me to come to the office and meet with the Parkinson

Society's officials. The latter were fascinated to learn how it all started,

because of course nobody bothered to preserve my grandfather's role in what

may be the Society's most important fundraising event. But for all their

supposed interest in learning about and restoring Superwalk's history, the

people in charge had no interest at all in returning Zaidy's name to the

walkathon--in giving him back his due, and respecting the agreement I had

with the organization. I even gave them scans of photos recording early Superwalks

and a history to put on their website. See if you can find any of that on

their site.

I’ve been working further on the novel, and have written other short

stories, including a science-fiction story cycle (one of the stories appeared

in Prairie Fire in 1995-96), and further stories about Lawrence Teitel,

the protagonist of Living Room. The sequel is tentatively entitled

Telescope, after the key story

in the cycle. In terms of academic work, I've continued to travel as

much as possible giving papers at conferences and published scholarly articles,

and I've been researching a book on apocalyptic science fiction covering

some of the material I've taught in a course on the subject. I also

had the "opportunity" to be Undergraduate Program Director in the English

Department (from 2008-2010) and to serve on, and even in some cases chair,

various committees. One of my proudest achievements as a prof is the

website "Grammar Man" (www.grammarman.ca),

designed to help students and others write better, or at least learn the

terms to use when discussing grammar and the most common errors. The

home page features a cartoon of Grammar Man drawn by a student in one of

my SF courses some years ago. I tell people there are two things I

like about the cartoon: the accurate rendering of my physique, and the way

the kid spelled "grammar"...