|

|

|

|

Advocacy

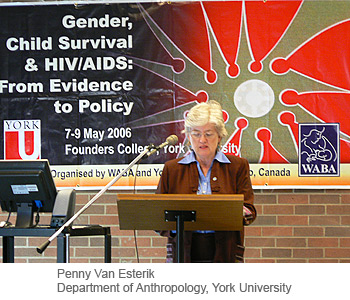

These words by Stephen Lewis inspired the recent conference at York University (May 2006) on Gender, Child Survival and HIV/AIDS: from Evidence to Policy. With support from the National Network on Environments and Women’s Health (NNEWH), and the participation of the Atlantic and Prairie centres ofexcellence of women’s health, York University’s anthropology department and the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA) organized this event to explore the gender implications of the transmission of HIV through breastfeeding. The conference welcomed health professionals, students, anthropologists, public health nurses, lactation consultants, and service providers of various kinds, some helping people living with HIV, others helping new mothers with breastfeeding. We focussed attention not on all those affected by HIV/AIDS, but rather on women and their children. We drew attention to a particular route of transmission, through breastmilk .The topic of HIV transmission through breastmilk is not easy to talk about. There are inevitable tensions between different stakeholders, as well as conceptual difficulties, scientific difficulties, policy difficulties, political difficulties and advocacy difficulties in addressing the problem of advising women who are HIV positive how to feed their infants. Since it was discovered that breastmilk could transmit HIV, there has been little public debate on interventions to prevent this transmission that do not also undermine child feeding programmes. Although we recognize the fact of HIV transmission through breastfeeding, the exact mechanisms are still unclear. But while the medical research on the transmission of HIV through breastmilk is progressing, the corresponding research on gender and AIDS is less developed, and less integrated into broader discussions ofchild survival. The transmission of HIV through breastmilk is only one small part of the problem facing women who are HIV positive. Women have higher viral loads, are often diagnosed later, and have poor access to care and medications. They are most often the caregivers for HIV positive family members, and most likely to be exposed to abuse and violence. Thus, gender inequity underlies the marginalization of women living with HIV, and discussions of child survival and feeding must be considered within the context of poverty, poor access to treatment, drugs and medical care, and a focus on preventing HIV transmission to infants rather than one that aims to improve the health of mothers and infants How did women get moved aside and ignored in the research agenda? When research attention was on women, it was often on sex workers, ignoring the fact that sex workers are also mothers. When research attention was on mothers, treatment was often directed to them only to prevent transmission to their infants. Women, mothers and children were often ignored when we looked at “risk groups” such as gay men or intravenous drug users, and when we shifted paradigms to talk about “risk behaviours”, breastfeeding mothers still didn’t fit in. Each shift in framework provided new ways to understand the disease. Blood and semen rather than breastmilk were of most interest. When attention focussed on semen as the carrier fluid, we learned a great deal from gay men’s groups. When the circulating medium was blood, we learned from hemophiliac support groups. What gets revealed when we look at breastmilk as the carrier fluid? What new processes can be understood when we look at mothers who breastfeed in the context of HIV/AIDS and at breastfeeding support groups? How do the questions change? For example, why was replacement feeding supported as an intervention rather than exclusive breastfeeding, when it has long term survival benefits for infants? And how can groups working to support breastfeeding mothers further support the research and policy work of AIDS advocacy groups? By focussing attention on mothers and children, and breastmilk rather than semen or blood, we move out of the discourse of blame and morality that often accompanies discussions of homosexuality, drug use and prostitution. But we face new challenges, as women are blamed for carrying out their expected gender roles as wives and mothers. How do we draw attention to women without defining mothers as a “risk group”, and mothering and breastfeeding as “risky behaviour”? The conference examined this question from a gender perspective. The subject is undertheorized because the storyline of AIDS is about other kinds of risky behaviour, not about mothers breastfeeding their children. We clearly need to develop some new storylines to help bridge the gaps between HIV/AIDS groups, women’s groups, child survival groups and breastfeeding advocacy groups. Future work will need to focus on the intersections between our various concerns – (such as care, conflict of interest, gender inequality, violence), and not on the boxes (HIV, gender, child survival, breastfeeding) The conference provided an opportunity to begin to tell these stories and to learn about the newest research on the subject of HIV transmission through breastmilk. Participants used the subject as a vehicle for exploring other gender issues related to HIV/AIDS, such as support for HIV positive women, how HIV/AIDS policy is made, and gender bias in research. Details on the workshops and papers is available in a report and CD prepared by conference co-sponsor, WABA. Following the conference, a joint statement was developed and circulated for endorsement and used at the International AIDS Conference in Toronto, August 2006. These documents are available on the WABA and National Network on Environments and Women’s Health (NNEWH) websites. Further Reading Cook, R.J. and B.M.Dickens. “Human Rights and HIV-Positive Women”. “International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 77: 55-63, 2002. INTEGRATING BREASTFEEDING AND GENDER INTO SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH IN THE CONTEXT OF HIV/AIDS

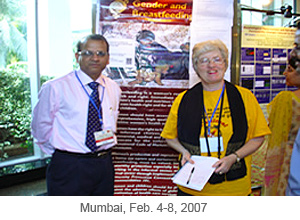

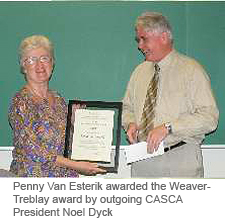

I include here the abstract of the paper I wanted to present at the conference, but as you can see from my brief report on the conference, I presented it as a poster instead. This paper explores the role of breastfeeding and breastfeeding advocacy in the context of HIV/AIDS. The transmission of HIV through breastmilk creates an excruciating dilemma for many mothers who are HIV positive. While epidemiological and biomedical research on the transmission of HIV through breastmilk and prevention-of-mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) is progressing, corresponding research on gender inequalities and the relation between sexual and reproductive health is less well developed, and less integrated into broader discussions of maternal health and child survival. Transmission through breastmilk is a relatively minor concern for AIDS researchers, considering the global demand for more effective prevention and better access to treatment worldwide. But it is of central importance to child feeding advocates who have seen programs to support breastfeeding mothers decimated over the past decade, with potential for devastating consequences. This paper reviews the advocacy and social mobilization initiatives of the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA) in the context of HIV/AIDS, including workshops, conferences, action kits, joint statements and participation in the IAC. WABA is a global network of individuals and groups working to protect, support and promote breastfeeding worldwide. The advocacy experience of attempting to build coalitions across different sectors revealed mammoth disconnections between how infant feeding and HIV/AIDS is framed in the global north and the global south; a lack of fit between breastfeeding and sexual and reproductive health; and an overall lack of social science research. In short, breastfeeding falls between the gaps of many international health agendas, and yet is key to achieving a number of the Millennium Development Goals. NGOs like WABA are crucial to this work. The paper concludes with an assessment of how to bridge the gaps between divergent frameworks, both geographically and conceptually, to create the possibility for an effective advocacy and policy response to HIV/AIDS. Report on the conference: Dear colleagues, just a brief note to report on my participation in the International Conference on Actions to Strengthen Linkages between Sexual and Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS, Mumbai, Feb. 4-8, 2007. WABA (World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action) sent me to this conference to see how breastfeeding issues could be integrated into sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and hiv/aids. I learned a great deal, but the meeting confirmed that breastfeeding (BF) is not significant in either SRH or hiv/aids discussions. I inserted discussions on breastfeeding where possible – particularly in the one open forum on gender equity. However, it did not fit into the established paradigms of either area. Often when I spoke of breastfeeding to hiv/aids policy people, the response was, “you mean PMTCT” (prevention of mother to child transmission)? Yet even there, within discussions of PMTCT, breastfeeding was only mentioned in the opening plenary sessions as a source of transmission of the virus. Perhaps this absence was a good thing in the hiv/aids discussions, because the subject obviously made people feel uncomfortable – as if not talking about it would make it go away. If it was the focus of too much attention, then work to support breastfeeding would be that much harder. Instaed I used my poster presentation as an advocacy opportunity to explain the importance of the issue and distribute WABA materials and the report from the York conference on the subject. I made a few connections with some wonderful colleagues who I hope to work with again. With them I could push the extent and complexity of the dilemma, and they came around to see the dangers of ignoring the topic and the potential for linking breastfeeding into other agendas. Why was BF absent? Primarily because the perspective of the hiv+ mother was rarely represented. It is the context of her decision that needs to be respected and understood. From the point of view of a health provider, this decision-making context is not well understood. Also, Indian delegates were adamant about following WHO’s approach to PPTCT and about encouraging exclusive breastfeeding. The contradictions between these two positions in practice were not acknowledged. It was as if lip service was paid to AFASS, and energy went to supporting EBF, at least at the level of policy. Delegates spoke of the need for more support to PMTCT because pregnant women are more vulnerable to hiv infections; more likely to receive blood transfusion or unsafe injections; their partners more likely to be having sex elsewhere during late pregnancy and postpartum, and will be at peak viral load when they resume sex with partner; and physiological changes in hormones and immune function during pregnancy increases risk. I learned a great deal from attending this meeting, but left with one burning question: If so much money has gone into PMTCT, and exclusive breastfeeding is considered a viable option, then how have PMTCT funds been used to make BF safer?? This is key question for policy makers and NGOs concerned with gender issues. DR. PENNY VAN ESTERIK: 2007 WEAVER-TREMBLAY AWARD What follows is a shortened version of the speech, “Nurturing Anthropology” given by Dr. Penny Van Esterik, upon receiving the 2006 Weaver-Tremblay award, presented to her in Toronto at CASCA in May 2007. As Dr. Naomi Adelson stated in her introductory remarks: Dr. Van Esterik’s renown as an advocacy anthropologist and, in particular, her extraordinary contribution to the fields of nutritional and gender/feminist anthropology is evidenced in her tireless work in advancing women’s causes and rights in national and international arenas for over three decades. Dr. Penny Van Esterik is a crusader for,and has devoted much of her career to, the most fundamental of human concerns: infant feeding. One of the very first to argue that breastfeeding is fundamentally a feminist issue, Van Esterik has written extensively on this subject and is best known for her academic and advocacy work in this area.

Everything Van Esterik writes is with an eye to her two main audiences: the academic and general or advocacy communities. As passionate as she is about her scholarly research and contributions, she is equally committed to the communities in which she works and for whom her work can have an affect. Margaret Mead once said: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful citizens can change the world—indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” Penny van Esterik has devoted her academic career to being one of those “thoughtful citizens” and her work has been and continues to be a force of academic rigour, excellence and sustained advocacy. Given the wealth of contributions she has already made and, with no sign of slowing down, Dr. Van Esterik exemplifies, and rightly deserves recognition for, the practice of applied anthropology in Canada. “NURTURING ANTHROPOLOGY” I share with Weaver and Tremblay a concern with taking public positions on matters of social and political concern—for me infant and child feeding; experience in interdisciplinary team work and a stubborn belief that what anthropologists do should and can matter to policy makers—nationally and internationally. I would like to address three aspects of “Nurturing Anthropology” through exploring three themes:

We choose our entry point into interpreting and observing the human condition. Mine is eating and feeding. Most of my academic work has linked in some way to food —food insecurity in Lao PDR, food and Buddhism in Thailand, but for most of my life, I kept breastfeeding advocacy work as a sideline, citizen action, distant from academic anthropology. This changed in 1985 when Robert Paine brought me to a workshop at Memorial University that explored advocacy in anthropology. 1. Nurturing Anthropology: child nurture from an anthropological perspective.My work is motivated by the fact that WHO estimates that over 5 million children under five die from malnutrition every year; and 1.5 million babies die each year because they were not adequately breastfed. The most cost-effective intervention for child survival—to support breastfeeding mothers—could prevent 15% of child deaths in lowincome countries. This support for breastfeeding mothers is not there. The interventions to protect breastfeeding seem to be left to small under-funded NGOs, like WABA, INFACT Canada, and IBFAN, to try to make international policy speak to local conditions, to translate the UN language into the local vernacular. I was active in the original Nestlé boycott, to limit the inappropriate marketing of infant formula inresource-poor communities. And I am reminded that no one makes a profit from breastfeeding. It is not a technological solution; it is a social, political and economic matter, related to the position and condition of women, and embedded in global processes. I began advocating for breastfeeding a couple of years after the birth of my daughter, Chandra, and later, began writing about breastfeeding for advocacy groups and academic audiences. I was a founding member of an NGO called the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action(WABA) based in Malaysia. This work has kept me involved with grass-roots consumer and women's groups around the world. This work has provided opportunities to travel to UN meetings and workshops related to infant and young child feeding. Every opportunity provided a new context for learning how women act to make changes in their communities, and what obstacles they face in feeding their children. Revisiting the perosonal experiences I have had over the years, it is clear that many are linked to the political economy of corporate-led globalization. The distrust of breastfeeding and breastfeeding advocacy groups in Canada was re-enforced this November when Chatelaine, a leading Canadian women’s magazine published an article headlined, “Breastfeeding Sucks”. The author refers to the “pro-breastfeeding tyrants”, the “evangelism” of the “boob squad” who use “scare tactics” to stifle women’s choices, and concludes, “We might have to suck up the pain of breastfeeding, but we can spit out the piety of the breastfeeding bullies” (Onstad 2006:60). This attitude suggests there is something very wrong in the way breastfeeding is represented in North America. As advocates pointed out, that month and the following month displayed three pages of Nestlé advertisements for baby foods. 2. Nurturing Anthropology: making anthropology more attentive to nurture and why this subject matters to anthropology Someone I had not seen for a while was surprised that I was still boycotting Nestlé’s products and promoting breastfeeding. “Why haven’t you moved on to something new, more anthropological?”, he asked. Why keep on with breastfeeding advocacy in the face of successes (“everybody does it”) and failures(particularly in the face of HIV/AIDS and contaminants in breast milk)? Wouldn't life be easier if we work from the assumption that breastfeeding is a lifestyle choice, and as one colleague recently said, just get on with it? This has been difficult for me to address. The Weaver-Tremblay award has forced me to try. But it is difficult to answer because the subject is not of interest to many. It is primarily of interest to women, a gendered potential of women’s bodies, but only for a short period in their lives – and not all women, only those who give birth – but not all those who give birth, breastfeed. So how do I justify concentrating on a subject that is only tangentially of interest to people, and further try to argue that it should be central concern to all anthropologists? Look around you. Not all of us breastfed. Not all of us were breastfed. And not all of us are interested in nurture and child feeding as an object of anthropological concern; but everyone in this room, in Toronto, alive in the world today survives by virtue of being fed and nurtured by others—first by mothers, then by others. We survive as individuals, as societies—even as a species, because of the nurturant care and feeding practices of others. So much for modernity’s rational autonomous individual! For whatever reason, the practices of nurture have not been fully examined by anthropologists who have placed more emphasis on aggression, competition, fear and structural violence as basic to the human condition. Our intellectual fascination with aggression, suffering, violence and fear—perpetuates an androcentric bias that has devalued the study of care and nurture. Feelings of vulnerability and fear pervade our public spaces. We feel frightened of difference and look for technological solutions that don’t work. But as anthropologists, our theories continue to privilege aggression and violence (gendered masculine) over care and nurture (gendered feminine), when both are accomplished by men and women. This has resulted in a failure to adequately theorize care and nurture, lest we slip into inappropriate essentialisms. Why has nurture been under theorized? A partial answer includes the desire to avoid.

I argue that nurture and care are at the core of the human condition; the place where biology and history, culture and language meet. Breastfeeding is not tightly programmed in humans. If it were an instinctual primate function, there would be no lactation failure, insufficient milk, cracked nipples, no feeling that if your father does not approve and you were told to feed in the bathroom, you could not let down, no need to choose between various alternative commercial products and no need to suppress lactation decision requiring an uncomfortable intervention. Instead, infant feeding, particularly breastfeeding depends on establishing a set of social relationships first between a mother and her newborn, but also with female relatives or friends who teach by example and provide assistance, including wet-nursing if necessary, material support in the form of food and care for the new mother and other members of the family, and emotional support (since emotions and hormones are interconnected). Anthropologists are just beginning to come to grips with Bateson's fierce awareness of the unity of reality, the connectedness of all systems. Self/other or subject/object oppositions cannot easily be applied to intersubjective activities such as breastfeeing or sexual relations. Both blur body boundaries, as people experience continuity with others. It is this continuity -this experience of other-as-self - that makes both breastfeeding and sex both powerful transforming experiences for some, and a terrifying loss of personal autonomy for others (or more often, both at the same time). Processes such as commensality, nurturance, intimacy and reciprocity emerge from human sentiments towards eating and feeding, and infant feeding creates the first contexts for these processes to develop. Breastfeeding and sharing food is the strongest reminder that we are not discrete beings; we emerge from other people, we merge into other people, our lives leak literally and figuratively into one another. Consider the interconnections between what we eat and what others eat. As a pregnant women eats, her food flavours the amniotic fluid, creating in the growing fetus a taste for flavours they will recognize in colostrum and later, breastmilk. As mothers continue eating local foods, they flavour the breastmilk further, setting the infant up to recognize and enjoy the flavours of household foods in the form of the complementary foods introduced ideally about six months of age, but already familiar—chillies, vanilla, garlic. Taste becomes one route to the external world, part of the sensory alignment between mother and child, further evidence that we are not the individual autonomous beings modernity tries to shape.

This relational reality is undertheorized, or rejected by both science and modernity, where the individual is defined as a discrete entity, an autonomous being. The discourse of autonomy and even rationality is unsuitable for explaining breastfeeding, infant feeding and sharing food. Autonomy has nothing to do with nurturance; autonomy turns nurturance into rational calculation; this is impossible for humans created by the nurturing acts of other humans and “society” in general. Violence builds on the inability to see self in other/other in self. Personal and structural violence works best when you deny the humanity of others, reminding them they don’t count, don’t exist, are subhuman, the axis of evil. And you certainly don’t feed the other. Nurture requires seeing self in other, feeling responsible for feeding others, starting with dependent infants, young children, and dependent elders, and reflected in the cycles of ritual feasts, potluck dinners and meals on wheels. 3. Nurturing Anthropology: the care and feeding of anthropology and anthropologists. At anthropology conferences, we feed each other and feed off each other, as at this conference where we don’t eat at all unless we can find friends to overeat with. Anthropologists have the privilege of moving back and forth between ivory towers and living with others. My perspective on nurture comes from Thai/Lao research on liang, to control and make something develop by feeding it. Parents liang children through breastfeeding and feeding them rice; you liang Buddhist monks, orchids, rice; politicians at election time liang their followers. Without understanding liang, such practices as feeding and hosting potential voters would be glossed as corruption. But once you feed someone you create a special relationship with them. Ethnographic experiences like this and the work of interpretation at the heart of anthropology are necessary to address the complexity of nurturing practices, including eating and feeding. They encourage us—require us—to connect the dots, and anthropology can provide the theoretical tools to do this. The best anthropological theory has clear specifiable relations to everyday life. To further the Weaver-Tremblay mandate, let us make theory accountable to praxis, rather than make praxis accountable to theory. Not that every theory has to be applied, but that every theory could be applied. Being a grounded person, food and eating has been my entry point for studying nurture, at the heart of the human condition. A retheorizing of nurture would require defining a new holism that reinstates a metanarrative of values; this would allow anthropologists to take a more informed role as social critics, and ensure that justice issues pervade the discipline. PENNY VAN ESTERIK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“You are fighting for the survival of women and infants, recognizing the excruciating dimension of HIV transmission, addressing it in a sophisticated, knowledgeable way, even if on occasion, it means replacement feeding in circumstances where you might wish otherwise. You’re fundamentally fighting for the emancipation of women, and there is no fight in this world more worthwhile” (WABA Report 2003:17).

“You are fighting for the survival of women and infants, recognizing the excruciating dimension of HIV transmission, addressing it in a sophisticated, knowledgeable way, even if on occasion, it means replacement feeding in circumstances where you might wish otherwise. You’re fundamentally fighting for the emancipation of women, and there is no fight in this world more worthwhile” (WABA Report 2003:17).  International Conference on Actions to Strengthen Linkages between Sexual and Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS

International Conference on Actions to Strengthen Linkages between Sexual and Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS Dr. Van Esterik has traveled far and wide in response to invitations to bring her work to such places as UNICEF, the Vatican, and diverse international councils on women’s and children’s health organizations. It is important to also note that her work has been translated into many languages including Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, Chinese and Russian. Furthermore, she has worked consistently since 1993 as a consultant to such international organizations as the World Food Program, the Population Council, CIDA, and UNICEF.The combination of applied scholar and activist is most abundantly apparent in her work for and with WABA, the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action. WABA is a non-governmental organization which focuses on social mobilization internationally for the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding. As a member of the International Advisory Committee, former head of the task force on Breast Feeding and Women’s Work and as one of the founding members of WABA, Dr. Van Esterik has been a significant and sustained force on the global scene of breastfeeding action.

Dr. Van Esterik has traveled far and wide in response to invitations to bring her work to such places as UNICEF, the Vatican, and diverse international councils on women’s and children’s health organizations. It is important to also note that her work has been translated into many languages including Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, Chinese and Russian. Furthermore, she has worked consistently since 1993 as a consultant to such international organizations as the World Food Program, the Population Council, CIDA, and UNICEF.The combination of applied scholar and activist is most abundantly apparent in her work for and with WABA, the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action. WABA is a non-governmental organization which focuses on social mobilization internationally for the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding. As a member of the International Advisory Committee, former head of the task force on Breast Feeding and Women’s Work and as one of the founding members of WABA, Dr. Van Esterik has been a significant and sustained force on the global scene of breastfeeding action. New humans first learn about the world through empathy and sympathy not violence and aggression; a mother learns about her infant, an infant learns about her mother through breastfeeding. This is not the only way to learn about an infant, but it is the easiest and fastest way to begin - the mindful body sets it up for you. [and when it goes wrong, and it can in hospital settings, it can be emotionally devastating].

New humans first learn about the world through empathy and sympathy not violence and aggression; a mother learns about her infant, an infant learns about her mother through breastfeeding. This is not the only way to learn about an infant, but it is the easiest and fastest way to begin - the mindful body sets it up for you. [and when it goes wrong, and it can in hospital settings, it can be emotionally devastating].