|

NATS 1700 6.0 COMPUTERS, INFORMATION AND SOCIETY

Lecture 16: The Internet and the World Wide Web

| Previous | Next | Syllabus | Selected References | Home |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

20 | 21 | 22 |

Introduction

-

The choice document for this lecture--in fact, for the whole course--is

About

the Internet. Histories of the Internet, a

comprehensive, well documented look at the social aspects of computer networking. The authors examine the present and the turbulent future, and especially the technical and social roots of the Net. About

the Internet. Histories of the Internet, a

comprehensive, well documented look at the social aspects of computer networking. The authors examine the present and the turbulent future, and especially the technical and social roots of the Net.

-

Very useful in the rest of the course is

Hobbes' Internet Timeline, which highlights

most of the key events and technologies which helped shape the Internet as we know it today. A more recent account is NSF and the Birth of the Internet.

Two other good sites with selected links are History of ARPANET,

and the Internet Society's A Brief History of the Internet. Hobbes' Internet Timeline, which highlights

most of the key events and technologies which helped shape the Internet as we know it today. A more recent account is NSF and the Birth of the Internet.

Two other good sites with selected links are History of ARPANET,

and the Internet Society's A Brief History of the Internet.

-

Read Jonathan Koppell's article No "There" There in the August 2000 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. The author

wonders why we use the term cyberspace. One reason, he suggests, "is to avoid downgrading it to the status

of a mere medium, and perhaps especially to avoid comparisons with television." This statement is almost seven years old. Do you

think the status of the Internet (or of the Web) has changed since then?

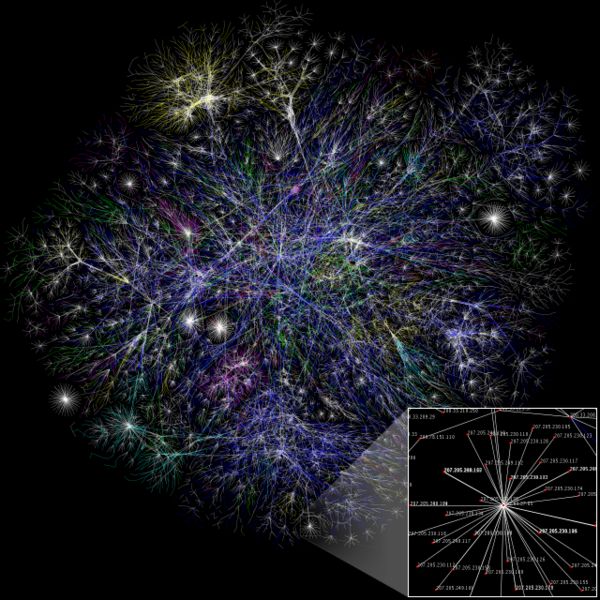

- To get an idea of "the spatial nature of computer communications networks, particularly the Internet, the World-Wide Web and other

digital or virtual 'places' that exist behind our computer screens, popularly referred to as cyberspace," visit Cyber Geography Research,

and An Atlas of Cyberspaces in particular, where

you will find "maps and graphic representations of the geographies of the new electronic territories of the Internet,

the World-Wide Web and other emerging Cyberspaces." Another interesting site is What Does the Internet Look Like, Jellyfish Perhaps?, which

offers a beautiful graphical representation of the net. Study the

MIDS Maps the Internet World.

For Internet statistics, visit Internet World Stats or

Zooknic Internet Geography Project . MIDS Maps the Internet World.

For Internet statistics, visit Internet World Stats or

Zooknic Internet Geography Project .

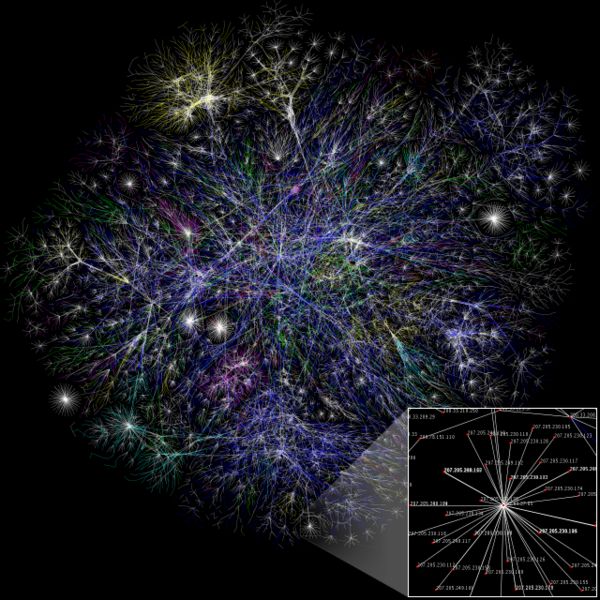

Visualization of the Various Routes Through a Portion of the Internet.

-

Read

Tim Berners-Lee's Frequently asked questions.

Berners-Lee is the inventor of the World Wide Web. Tim Berners-Lee's Frequently asked questions.

Berners-Lee is the inventor of the World Wide Web.

-

Inventing the Internet by Janet Abbate (The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1999), "focuses on the

social and cultural factors that influenced the Internet's design and use. She unfolds an often twisting tale of

collaboration and conflict among a remarkable variety of players, including government and military agencies, computer

scientists in academia and industry, graduate students, telecommunications companies, standards organizations and network

users." Colline Report: The Collective Invention of the Word-Wide Web, illustrates

the European views on the history and nature of the net.

-

A great site is the Resource Center for Cyberculture Studies.

The Center "is an online, not-for-profit organization whose purpose is to research, study, teach, support, and create

diverse and dynamic elements of cyberculture. Collaborative in nature, RCCS seeks to establish and support ongoing

conversations about the emerging field, to foster a community of students, scholars, teachers, explorers, and builders

of cyberculture, and to showcase various models, works-in-progress, and on-line projects. Currently, the site contains

a collection of scholarly resources, including university-level courses in cyberculture, events and conferences, an

extensive annotated bibliography, and a monthly book review.

-

Samuel Ebersole's essay on Media Determinism in Cyberspace

is also a thoughtful philosophical analysis of cyberspace: "Only after understanding the philosophical assumptions

made by the technology itself, and by those who are creating and using the technology, can we begin to truly understand

the value-laden choices that are ours to make."

- You may also enjoy visiting 60 Days to Launch: The Anatomy of an Internet Start-Up. "Beyond

the ballyhoo of the business pages, and manic swings of the Nasdaq, the American economy is in transition: from the way

it works to the work it creates. 60 Days to Launch reveals these changes. You will be witnesses. These documentary

episodes are a fascinating look at what a small group of entrepreneurs can do given a conference room, plenty of caffeine,

and a six-month supply of Hot Tamale candies. We'll post a new clip every day for 60 days with the hope that you will see

what we watched unfold."

- For a taste of the role of the internet in scientific research , consider the following press release by Iowa State University.

Astronomical Networks Use Earth as a Telescope

AMES, Iowa -- Astronomers, always looking for larger, more-powerful

telescopes to peer into the skies with,are now using the Earth itself

as a telescope platform.

By connecting several individual observatories via communications

networks like the Internet, astronomers have been successful in using

the connected telescopes as a single instrument the size of Earth,

says Steve Kawaler, professor of physics and astronomy at Iowa State

University. Doing this has not only breathed new life into observatories,

but also has led to unprecedented views of astronomical objects.

Kawaler will describe the international astronomical efforts of the

Whole Earth Telescope (WET) at the 2001 American Association for the

Advancement of Science meeting in San Francisco, Feb. 15-20. Kawaler's

presentation is part of the symposium, "A Telescope the Size of Earth:

Global Astronomy Networks," which will be 9 a.m.-12 noon, Feb. 18.

Kawaler helped organize the symposium with fellow ISU astronomer Lee

Anne Willson.

Symposium speakers will make presentations on several worldwide

observing efforts. Through cooperation of astronomical teams across

the globe, several efforts have been underway including a survey of

the entire sky, 24-hour observational coverage of a single astronomical

object and very-long-baseline interferometry for high spatial

resolution in the radio region of the spectrum.

The WET is both special and typical of these collaborations, which

must cut through geographical and political barriers, said Kawaler,

WET director. The WET is a network of 29 small- to medium-sized optical

observatories in dozens of countries ranging from Austria to Chile,

China and the United States. It is headquartered at Iowa State University.

"By linking these telescopes together," Kawaler said, "we can monitor

astronomical objects in ways that were simply not possible before.

We can learn more about these objects because we can monitor them

around the clock, essentially using Earth's rotation and turning on

and off observatories as they come into and pass out of the viewing

area of an object."

"The WET basically is astronomy via the web," Kawaler added. "Through

the use of the Internet we can have observational data from virtually

anywhere in the world sent to us for analysis and interpretation."

Kawaler uses white dwarf star observations with the WET as an example

of the unique capabilities of such a collaboration. White dwarf stars

represent the final phase of the life of a star like our Sun. Studying

white dwarfs not only allows astronomers to study what will happen to

the Sun and solar system, but also show astronomers the physics of

matter under extreme conditions. Through WET observations, astronomers

can probe the interiors of white dwarfs and other stars through the new

science of stellar seismology.

"Certain stars undergo natural vibrations that can be detected with

sensitive time-series photometry and/or spectroscopy," Kawaler said.

"Since the signal we seek is an unbroken time-series to allow

determination of the vibration frequencies, data from a single-site

is usually incapable of uniquely identifying the pulsation modes,

no matter how large the telescope being used.

"In many cases, observational goals can be achieved using smaller

telescopes in well-coordinated global networks," Kawaler said.

"These networks can provide extended monitoring of target stars

continuously for days to weeks."

Over the years, WET has observed dozens of stars in 20 separate

observing campaigns, Kawaler added. Among the more interesting subjects

is a star (BPM 37093) that could be made up of crystalline carbon and

oxygen.

Another important project involves a pair of stars (PG 1336) that

orbit each other 10 times a day and are separated from each other only

by a bit more than the distance of the Earth to the moon (roughly

230,000 miles). One of those two stars also vibrates quickly, giving

astronomers a way to study how this system was formed and hinting as

to what its future might hold.

"Above all, perhaps, the WET demonstrates how the pursuit of science

can transcend political and cultural boundaries," Kawaler said.

"International cooperation doesn't only have to be a response to a global

crisis, but also can be for the joy of discovery."

Here is the link to the Whole Earth Telescope Project .

- Read a not so recent State of the Internet 2001,

prepared by ITTA (International Technology & Trade Associates) for the United States Internet Council. "The Report

provides an overview of recent Internet trends and examines how the Internet is affecting both business and social

relationships around the world. This year’s Report has also expanded its vision to include sections covering the

international development of the Internet as well as the rapid emergence of wireless Internet technologies."

Compare it now to the more recent State of the Internet

dated November 2006, and you will see how the commercialization of the Internet has proceeded at a dizzying pace.

Topics

- The first date to appear in Hobbes' Internet Timeline is 1957. In that year the USSR launched the first artificial

satellite, Sputnik. The reaction in the Western world, especially in the US, was one of utter panic.

The Americans felt that their entire nuclear 'defense' system was now vulnerable: if the Russians had rockets powerful

enough to place payloads in earth orbit, they could certainly use the same rockets to deliver nuclear missiles anywhere

on the surface of the earth. Furthermore, the Americans thought, the Russians have been so successful because they

educate their youth thoroughly, teaching them a lot of science. These thoughts sparked many reforms and initiatives.

Among them, and of interest to us, was the creation, by the US Department of Defense, of the Advanced Research

Projects Agency or ARPA in 1958. ARPA was later renamed DARPA, Defense Advanced Research Projects

Agency. The basic idea was to use distributed telecommunications networks, and in particular computer

networks. If suitably designed, such networks would considerably decrease the vulnerability of the military

infrastructure, because no one location would be critical. It is important to notice that at that time computers

were considered essentially as 'number crunchers,' and in fact they had been so used by the military, business and

the universities.

- Probably the most influential person in DARPA was J C R

Licklider, who was, in the most positive sense of the word, a great visionary (see Lecture 10).

He was first head of the computer research program at DARPA. From the very beginning he realized the crucial importance

of networking. He was able to attract some of the best minds to DARPA, from the military and from the universities.

It is very interesting that business, although openly invited, declined to participate in this effort. In fact, business

did not become interested in networking and the Internet until the late '80s. What is equally interesting is that,

despite the military nature of the project--a fact that should have been quite important to a lot of intellectuals

in the '60s--Licklider was very successful in securing the participation of many university researchers and graduate

students, and to establish a surprisingly open and exciting atmosphere.

- One of the most difficult problems DARPA faced was the utter diversity of the computers then in use. Each piece

of hardware and software was essentially unique, and to connect together machines so different from each other

presented formidable challenges. The solution was to formulate uniform transmission protocols, i.e. procedures

for reducing the inputs and outputs of the various machines to a common format in the transmission lines, and to leave

it up to the local operators to convert the common format to something intelligible by the various machines.

- in 1965 a TX-2 computer in Massachusetts and a Q-32 computer in California were connected with a low-speed dial-up

telephone line, and the first WAN or wide-area computer network was born. It was called ARPANET. These computers, which

already incorporated the time-sharing architecture, were able to carry on their normal functions, while at the

same time exchanging data between them. However, the circuit switched telephone system appeared completely

inadequate. The solution was to adopt the newly developed packet switching technique. This technology, which

required the deployment of special, high-speed (well.., 50 kbps!) digital lines, used addresses included in each bundle

or packet of data to route them to the intended destination. By 1969 the network included four computers (hosts).

In 1972 ARPANET was demonstrated in public, very successfully.

The Geography of the Internet (January 1999)

- ARPANET kept growing, thanks also to parallel developments in radio and satellite communications, but especially

to the introduction of "a key underlying technical idea, namely that of open architecture networking...In an

open-architecture network, the individual networks may be separately designed and developed and each may have its

own unique interface which it may offer to users and/or other providers, including other Internet providers. Each

network can be designed in accordance with the specific environment and user requirements of that network. There are

generally no constraints on the types of network that can be included or on their geographic scope, although certain

pragmatic considerations will dictate what makes sense to offer."

[ from A Brief History of the Internet ]

- The open-architecture network allowed separate networks (ARPANET, USENET, BITNET, JANET, NSFNET, etc.) to be

connected together into the inter-net. Once again, the rest is history. Please note: I am certainly not

suggesting that this brief sketch is an adequate history of the Internet. I do believe however that it is a sufficient

introduction to such history. The links and other readings provided here should allow you to fill in the details to

any degree you may like.

- Let me now point out some important passages in the Introduction and chapter 1 of Gordon Graham's book.

In the Introduction he writes that to determine the real issues concerning the Internet and their ramifications

"it is necessary to set [these issues] in the wider context of the philosophy of technology, which is to say,

within an understanding of the place of technology within human culture as a whole..." (on p. 3) We must always

remind ourselves of this wider scope.

- In Chapter 1, Graham looks at two extreme, but not new, views of technology: (Neo-)Luddism and Technophilia. The

Unabomber's Manifesto represents "the

most dramatic recent expression of a Neo-Luddism,...which is more widely held and deserves serious attention."

Graham's response is that "what has been invented cannot be uninvented, and once invented someone somewhere will

want to use it and succeed in doing so. In the case of the Internet, there is no need to speculate on 'someone,

somewhere.' Such large numbers of people, everywhere as it seems, have taken it up that we can be sure it will

not go away." (p. 7)

- The other extreme "is most evident in Technophiles: those who believe that technological innovation is a

cornucopia which will remedy all ills. The defining characteristic of technophilia is its assumption that the

most technologically advanced is the best." A corollary of this assumption is the belief "that countries

and individuals who want to increase or preserve their prosperity must invest heavily in hi-tech." Graham's

first response is that "it is not difficult to find evidence that under the influence of an unquestioning

ideology, large errors have indeed been made, and made in the recent past. Some of these rest upon false predictions,

many have involved considerable, but unnecessary expenditure, and all of them have, in one way or another, been a

waste of time." (p. 9-10) He then adds: "[technophiles assume] that the value of technology is neutral...

[they] assume that the value of some piece of technology is wholly derived from the purpose it serves; if new

technology serves some such purpose better than that which it threatens to replace, then it is to be welcomed.

This truth of this, if true it be, does not imply of course that every and any innovation is valuable." (p. 13)

Both these rebuttals are expressions of a certain "critical realism."

- "The media looms so large in our vision of the future that we may fail to recognize

their importance in the past, and the present can look like a time of transition, when the

modes of communication are replacing the modes of production as the driving force of history.

I would like to dispute this view, to argue that every age was an age of information, each in

its own way, and that communication systems have always shaped events." So says Robert

Darnton, in

Paris: The Early Internet, an

article that appeared recently in the New York Review of Books. He starts with a simple

question: "How did you find out what the news was in Paris around 1750?," and with

a wealth of evidence he proceeds to draw the picture of a truly networked city, a quarter of

a millennium ago. Paris: The Early Internet, an

article that appeared recently in the New York Review of Books. He starts with a simple

question: "How did you find out what the news was in Paris around 1750?," and with

a wealth of evidence he proceeds to draw the picture of a truly networked city, a quarter of

a millennium ago.

Or visit The Word on the Street , a collection

of broadsides published between 1650 and 1910, and placed online by the The National Library of Scotland.

There you can read about "crime, politics, romance, emigration, humour, tragedy, royalty and superstitions."

Precisely what the web offers nowadays.

For something a bit more recent, see T Standage, The Victorian

Internet, Berkeley Books, New York, 1999. This short book narrates the history of

the telegraph, a technology which connected together the people not just of one city, but of

most of the nineteenth century world.

Questions and Exercises

- List the main characteristics of the global information society.

- The original outline of this lecture was written a few years ago. It has been updated, but probably not sufficiently.

What do you think should be added to bring it reasonably up to date?

-

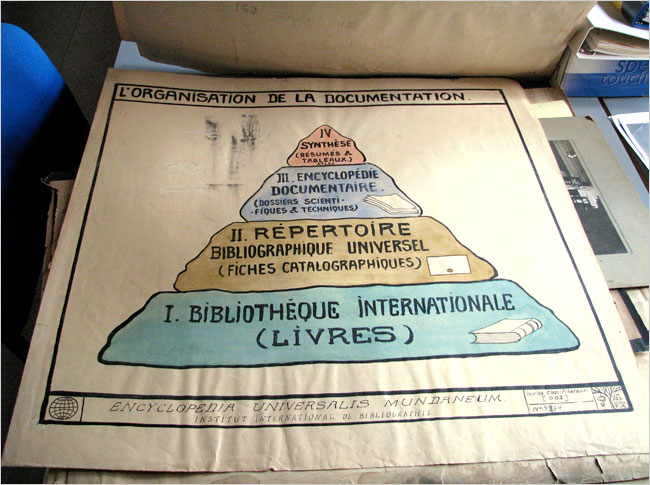

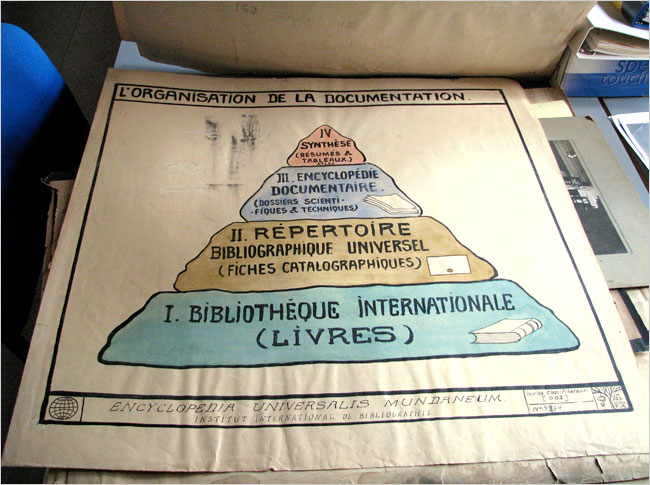

Although the creation of the World Wide Web is justly credited to Tim Berners-Lee, the history of the idea of a globally

accessible knowledge network goes back several years. We have already mentioned Vannevar Bush and Licklider. We should

also acknowledge Paul Otlet , who already in 1934 had developed

and partially realized a complex system that in many ways anticipates the Web and one of the Web's most crucial element, the hyperlink.

Read

The Web Time Forgot,

an article by Alex Wright, which appeared in the June 17, 2008 issue of the New York Times:

The Web Time Forgot,

an article by Alex Wright, which appeared in the June 17, 2008 issue of the New York Times:

"In 1934, Otlet sketched out plans for a global network of computers (or

'electric telescopes,' as he called them) that would allow people to

search and browse through millions of interlinked documents, images,

audio and video files. He described how people would use the devices to

send messages to one another, share files and even congregate in online

social networks. He called the whole thing a 'reseau,' which might be

translated as 'network' or arguably, 'web.'

"Historians typically trace the origins of the World Wide Web through a

lineage of Anglo-American inventors like Vannevar Bush, Doug Engelbart

and Ted Nelson. But more than half a century before Tim Berners-Lee

released the first Web browser in 1991, Otlet (pronounced ot-LAY)

described a networked world where 'anyone in his armchair would be able

to contemplate the whole of creation.'"

One of Paul Otlet's Manuscripts

Visit also Le Mundaneum , "Créé à l’initiative

de deux juristes belges, Paul Otlet et Henri La Fontaine, le projet visait à rassembler l’ensemble des connaissances du monde

et à les classer selon le système de Classification Décimale Universelle (CDU) qu’ils avaient mis au point."

Picture Credit: Wikipedia · An Atlas of Cyberspaces · The New York Times

Last Modification Date: 08 April 2009

|

![]() About

the Internet. Histories of the Internet, a

comprehensive, well documented look at the social aspects of computer networking. The authors examine the present and the turbulent future, and especially the technical and social roots of the Net.

About

the Internet. Histories of the Internet, a

comprehensive, well documented look at the social aspects of computer networking. The authors examine the present and the turbulent future, and especially the technical and social roots of the Net.![]() Hobbes' Internet Timeline, which highlights

most of the key events and technologies which helped shape the Internet as we know it today. A more recent account is NSF and the Birth of the Internet.

Two other good sites with selected links are History of ARPANET,

and the Internet Society's A Brief History of the Internet.

Hobbes' Internet Timeline, which highlights

most of the key events and technologies which helped shape the Internet as we know it today. A more recent account is NSF and the Birth of the Internet.

Two other good sites with selected links are History of ARPANET,

and the Internet Society's A Brief History of the Internet.![]() MIDS Maps the Internet World.

For Internet statistics, visit Internet World Stats or

Zooknic Internet Geography Project .

MIDS Maps the Internet World.

For Internet statistics, visit Internet World Stats or

Zooknic Internet Geography Project .

![]() Tim Berners-Lee's Frequently asked questions.

Berners-Lee is the inventor of the World Wide Web.

Tim Berners-Lee's Frequently asked questions.

Berners-Lee is the inventor of the World Wide Web.

![]() Paris: The Early Internet, an

article that appeared recently in the New York Review of Books. He starts with a simple

question: "How did you find out what the news was in Paris around 1750?," and with

a wealth of evidence he proceeds to draw the picture of a truly networked city, a quarter of

a millennium ago.

Paris: The Early Internet, an

article that appeared recently in the New York Review of Books. He starts with a simple

question: "How did you find out what the news was in Paris around 1750?," and with

a wealth of evidence he proceeds to draw the picture of a truly networked city, a quarter of

a millennium ago.![]() The Web Time Forgot,

an article by Alex Wright, which appeared in the June 17, 2008 issue of the New York Times:

The Web Time Forgot,

an article by Alex Wright, which appeared in the June 17, 2008 issue of the New York Times: