U n i v e r s i t é Y O R K U n i v e r s i t y

ATKINSON FACULTY OF LIBERAL AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES

SCHOOL OF ANALYTIC STUDIES & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

S C I E N C E A N D T E C H N O L O G Y S T U D I E S

STS 3700B 6.0 HISTORY OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

ATKINSON FACULTY OF LIBERAL AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES

SCHOOL OF ANALYTIC STUDIES & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

S C I E N C E A N D T E C H N O L O G Y S T U D I E S

STS 3700B 6.0 HISTORY OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Lecture 22: Concluding Remarks

| Prev | Search | Syllabus | Selected References | Home |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

Topics

-

"Technology is not the sum of the artifacts, of the wheels and gears, of the rails and electronic transmitters. Technology is a system. It entails far more than its individual material components. Technology involves organization, procedures, symbols, new words, equations, and, most of all, a mindset."

Ursula Franklin -

"As the Nineties proceed, finding a link to the Internet will

become much cheaper and easier. Its ease of use will also improve,

which is fine news, for the savage UNIX interface of TCP/IP leaves

plenty of room for advancements in user-friendliness. Learning the

Internet now, or at least learning about it, is wise. By the

turn of the century, 'network literacy,' like 'computer literacy'

before it, will be forcing itself into the very texture of your

life." These words are from Bruce Sterling's

Short History of the Internet.

Notice that this article was written in 1993, before the emergence of the Web.

Consider the visionary words quoted above. Consider the technological future described by Vannevar Bush, or

E M Forster's story The Machine Stops, and compare these

projections with what is actually unfolding today, before our own eyes. Clearly, it is not easy to predict

the path or paths that technology in general, and even specific technologies, will take.

On the one hand, there seem to be certain patterns, certain technological templates, which recur, although

under different forms. through most cultures and ages. In the case of 'information,' for example, here's

what Robert Darnton, in his article "Paris: The Early Internet," which appeared in the June 29, 2000

issue of The New York Review of Books: "Among the many prophecies about the century we have just entered, we hear

a great deal about the information age. The media loom so large in our vision of the future that we may fail to recognize

their importance in the past, and the present can look like a time of transition, when the modes of communication are

replacing the modes of production as the driving force of history. I would like to dispute this view, to argue that

every age was an age of information, each in its own way, and that communication systems have always shaped events."

Visit Gerard J Holzmann and Björn Pehrson's The Early History of Data Networks

(a very good resource for the history of the telegraph and of many other early communication technologies)

and read the three short letters, and the editorial response to the first, which appeared in Gentleman's Magazine

in 1794. These documents describe the invention of the 'télégraphe' by William Amontons, which was then

perfected by Claude Chappe, and its adoption by the French Convention.

Short History of the Internet.

Notice that this article was written in 1993, before the emergence of the Web.

Consider the visionary words quoted above. Consider the technological future described by Vannevar Bush, or

E M Forster's story The Machine Stops, and compare these

projections with what is actually unfolding today, before our own eyes. Clearly, it is not easy to predict

the path or paths that technology in general, and even specific technologies, will take.

On the one hand, there seem to be certain patterns, certain technological templates, which recur, although

under different forms. through most cultures and ages. In the case of 'information,' for example, here's

what Robert Darnton, in his article "Paris: The Early Internet," which appeared in the June 29, 2000

issue of The New York Review of Books: "Among the many prophecies about the century we have just entered, we hear

a great deal about the information age. The media loom so large in our vision of the future that we may fail to recognize

their importance in the past, and the present can look like a time of transition, when the modes of communication are

replacing the modes of production as the driving force of history. I would like to dispute this view, to argue that

every age was an age of information, each in its own way, and that communication systems have always shaped events."

Visit Gerard J Holzmann and Björn Pehrson's The Early History of Data Networks

(a very good resource for the history of the telegraph and of many other early communication technologies)

and read the three short letters, and the editorial response to the first, which appeared in Gentleman's Magazine

in 1794. These documents describe the invention of the 'télégraphe' by William Amontons, which was then

perfected by Claude Chappe, and its adoption by the French Convention.

"The new-invented telegraphic language of signals is a contrivance of art to transmit thoughts, in a peculiar language, from one distance to another, by means of machines, which are placed at different distances of between four and five leagues from one another, so that the expression reaches a very distant place in the space of a few minutes… At present, the telegraphic language of signals is prepared in such a manner, that a correspondence may be conducted with Lille upon every subject, and that every thing, nay even proper names, may be expressed; an answer may be received, and the correspondence thus be renewed several times a day. The machines are the invention of Citizen Chappe, and were constructed before his own eyes; he directs their establishment at Pariss… The greatest advantage which can be derived from this correspondence is, that, if one chuses, its object shall only be known to certain individuals, or to one individual alone, or two opposite distances, so that the Committee of Public Welfare may now correspond with the Representative of the People at Lille without any other persons getting acquainted with the object of the correspondence. It follows hence that, were Lille even besieged, we should know every thing at Paris that would happen in that place, and could send thither the Decrees of the Convention without the enemy's being able to discover or to prevent it."

On the other hand, there is a strangely ephemeral quality to technology. For example, here is Bruce Sterling's The DEAD MEDIA Project: A Modest Proposal and a Public Appeal where he says: "Plenty of wild wired promises are already being made for all the infant media. What we need is a somber, thoughtful, thorough, hype-free, even lugubrious book that honors the dead and resuscitates the spiritual ancestors of today's mediated frenzy. A book to give its readership a deeper, paleontological perspective right in the dizzy midst of the digital revolution. We need a book about the failures of media, the collapses of media, the supercessions of media, the strangulations of media, a book detailing all the freakish and hideous media mistakes that we should know enough now not to repeat, a book about media that have died on the barbed wire of technological advance, media that didn't make it, martyred media, dead media. THE HANDBOOK OF DEAD MEDIA. A naturalist's field guide for the communications paleontologist."

-

A very interesting and well documented case that can teach us much is the telegraph, which

Tom Standage, in his The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-line Pioneers

(New York, 1998) considers, as both a social and technological phenomenon, a remarkable forerunner of the internet. Visit

The Victorian Internet, where, in addition to a review of Standage's book,

you can find a veritable mine of related resources.

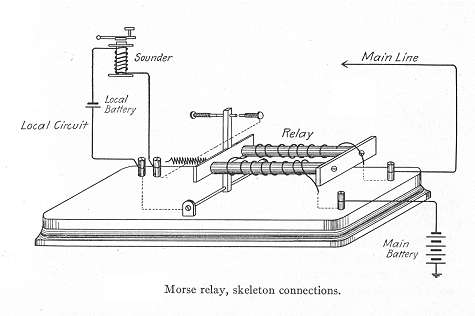

Morse Relay: Skeleton Connections

The studies mentioned above basically conclude that "perhaps one of the most fundamental technologies spawned by the telegraph was electricity itself. One young telegraph operator, Thomas Edison, soon turned from fiddling with new hacks on telegraph equipment to electricity, moving on to start the first systematic commercial electrical distribution systems." [ from The Victorian Internet ] If this claim may appear somewhat exaggerated, consider that the telephone was definitely a technology directly driven by the continuing efforts to improve the telegraph. The telephone was so successful (mostly because it allowed person-to-person communication) that its diffusion led to the death of the telegraph. "When Queen Victoria's reign ended in 1901, the telegraph's greatest days were behind it. There was a telephone in one in ten homes in the United States, and it was being swiftly adopted all over the country." [ Standage, op. cit., p. 205 ] Why all these cautionary tales? Because any course on the history of any technology must inevitably ask if the past has anything to teach us about the future, or, if you prefer, whether the phenomena under study possess any degree of 'universality.' In other words, can we conclude from our survey that the 'urge to compute and communicate' is part of what makes us human? Hint: all kinds and levels of life are equipped with some form of computing and communication abilities. What is there that makes the human case so special, if any? Another question that also arises in the study of technology is whether we can speak of 'progress.' Is the modern computer, and the global networks it has made possible, not only an improvement over, say, the telegraph, or radio, or television, and the 'networks' they have led to, but also the clear direction in which any future development will necessarily take us? As you know, the notion of 'human progress' has been the subject of a widespread and thorough 'deconstruction.' At the same time, the excesses of deconstruction (and more generally, of postmodernism) have also been receiving much negative scrutiny recently, and even apart from this kind of 'cultural war,' some of the recent developments we reviewed in the previous lecture may be pointing at radical departures from the technologies we are now familiar with. The debate is quite open-ended for the moment. -

At the end of our long survey, after examining so many event and so much data, perhaps the most important residue is the

questions we are left with, which I have briefly articulated above. These questions are not primarily technological in

nature. As Ursula Franklin says, they have to do with our mindset.

"Societies are organisms that evolve through and with their members; they are not mechanisms to be assembled and disassembled at will. Yet the potential of doing just that exists to date on a global scale because of the characteristics of asynchronistic technologies. Thus the struggle to understand and steer the interaction between the bitsphere and the biosphere is the struggle for community in the broadest ecological context. This is a collective endeavour that no group or conglomerate can do on its own. Most of our social and political institutions are both reluctant and ill-equipped to advance such tasks. Yet if sane and healthy communities are to grow and prevail, much more weight has to be placed on maintaining the non-negotiable ties of all people to the biosphere."

Here is an interesting article by Joichi Ito, Emergent Democracy, which begins thus:"Proponents of the Internet have committed to and sought for a more intelligent Internet where a direct democracy could be enabled and help rectify imbalance and inequalities of the world. Instead, the Internet today is a noisy environment with a great deal of power consolidation instead of the flat democratic Internet many envisioned. In 1993 Howard Rheingold wrote 'We temporarily have access to a tool that could bring conviviality and understanding into our lives and might help revitalize the public sphere. The same tool, improperly controlled and wielded, could become an instrument of tyranny. The vision of a citizen-designed, citizen-controlled worldwide communications network is a version of technological utopianism that could be called the vision of the electronic agora. In the original democracy, Athens, the agora was the marketplace, and more—it was where citizens met to talk, gossip, argue, size each other up, find the weak spots in political ideas by debating about them. But another kind of vision could apply to the use of the Net in the wrong ways, a shadow vision of a less utopian kind of place—the Panopticon.' Since then he has been criticized as being naive about his views. This is because the tools and protocols of the Internet have not yet evolved enough to allow the emergence Internet democracy to create a higher-level order. As these tools evolve we find the verge of an awakening of the Internet. This awakening will facilitate a political model enabled by technology to support those basic attributes of democracy, which have eroded as power has become concentrated within corporations and governments. It is possible that new technologies may enable a higher-level order, which in turn will enable a form of emergent democracy that will more effectively manage complex issues than a representative democracy in its current form, which will enable a form of emergent direct democracy capable of managing complex issues more effectively than the current form of representative democracy."

Readings, Resources and Questions

-

This lecture's epigraph is a quote from Ursula M Franklin's The Real World of Technology (Revised Edition. Anansi, 1990, 1999).

The first edition of the book is also available on the Internet in RealAudio format: Massey Lectures 1989: Ursula Franklin,

but lacks the four important chapters on information technology added in 1999. This is a fundamental text about technology

and human values, and should be compulsory reading in any course dealing with technology and society.

"…human beings seek and have always sought such things as health, prosperity, entertainment and

education. To assess the value of technology, therefore, we need only to ask whether or not it more

adequately puts these things within our grasp. What this way of thinking excludes, however, is the

possibility that technological innovation might not merely alter but transform the world

with which we are familiar—which is to say, transform the ends we seek and thus the values we espouse—by

altering our conceptions of what health, entertainment and so on, are."

These words are taken (p. 17) from an interesting study of the Internet by Gordon Graham:

The Internet: A Philosophical Inquiry (London & New York: Routledge. 1999).

Read again Vannevar Bush's

As We May Think (1945).

Read also Edward Morgan Forster's

As We May Think (1945).

Read also Edward Morgan Forster's  The Machine Stops (1909). These

two, vastly different pieces convey, probably more directly than any explanation can, the historicity of our images of the future—whether

technological or otherwise. More generally, you may want to visit Yesterday's Tomorrows: Past Visions of the American Future,

"a traveling exhibition that explores the history of the future—our expectations and beliefs about things

to come. From ray guns to robots, to nuclear powered cars, to the Atom-Bomb house, to predictions and inventions that

went awry." Finally, it will also be useful to read

The Machine Stops (1909). These

two, vastly different pieces convey, probably more directly than any explanation can, the historicity of our images of the future—whether

technological or otherwise. More generally, you may want to visit Yesterday's Tomorrows: Past Visions of the American Future,

"a traveling exhibition that explores the history of the future—our expectations and beliefs about things

to come. From ray guns to robots, to nuclear powered cars, to the Atom-Bomb house, to predictions and inventions that

went awry." Finally, it will also be useful to read  50 Years After 'As We May Think': The Brown/MIT Vannevar Bush Symposium.

Finally, read a Conversation With Marc Andreessen on Wired News. "It's been 10 years since Marc

Andreessen and colleagues at the University of Illinois launched Mosaic, the first browser to navigate the World Wide Web.

But according to Andreessen, we're still less than halfway through the generational cycle of adoption that will shape how we

ultimately incorporate the Internet into our daily lives."

50 Years After 'As We May Think': The Brown/MIT Vannevar Bush Symposium.

Finally, read a Conversation With Marc Andreessen on Wired News. "It's been 10 years since Marc

Andreessen and colleagues at the University of Illinois launched Mosaic, the first browser to navigate the World Wide Web.

But according to Andreessen, we're still less than halfway through the generational cycle of adoption that will shape how we

ultimately incorporate the Internet into our daily lives."

-

Here are some further references to the history of the telegraph and… the 'Victorian internet.'

A Tobler, Some Words on the Life and Work of Mr Baudot (1903)

Frank L Pope, Modern Practice of the Electric Telegraph (1871) Neal McEwen's A Tribute to Morse Telegraphy and Resource for Wire and Wireless Telegraph Key Collectors and Historians is a veritable treasure trove of material concerning telegraphy, and includes an on-line museum. Effective January 27, 2006, Western Union has discontinued all Telegram and Commercial Messaging services. The long history of the telegraph has officially ended! See Western Union Telegram.

© Copyright Luigi M Bianchi 2001, 2002, 2003

Picture Credits: Telegraph Lore

Last Modification Date: 02 February 2006

Picture Credits: Telegraph Lore

Last Modification Date: 02 February 2006