Sarah Hornsey was one of two people with my family name who were convicted of petty crimes in England and sentenced to transportation to Australia.

Her sentence by the General Session of Northampton Assizes on 20 December 1850 was for the unusual period of ten years.[1] Like most transportees, she had prior convictions. At her trial in February of the same year, at which she pleaded guilty of stealing “a clock, two blankets, a pillow and a set of fire-irons,” the court’s Recorder noted that Sarah had been convicted previously. After her release from prison for that earlier, unspecified offence, some “benevolent ladies” had provided her with lodgings, from which she had promptly stolen the clock and other items. The Recorder went on to warn Sarah that, if the previous case had come before him, he would have had no option but to transport her. As it was, he sentenced her to six months’ imprisonment.[2]

Not long after her release, Sarah was again found guilty of theft. In the company of Elizabeth Wright and Hannah Burgess, she went into a clothier’s shop and picked out some flannel cloth, a scarf, a gentleman’s pocket handkerchief, and a dress. The three women left, saying that they would pick up and pay for their purchases on their way home. After their departure, the shop assistant found that a dress was missing. A police constable was called, and the women were detained and searched in a nearby shop. The dress was found in Sarah Hornsey’s basket. She was found guilty of theft and sentenced to transportation, as she had been warned back in February. Elizabeth and Hannah were acquitted of this crime.[3]

One of Sarah Hornsey’s other sentences was for three months for “deserting her children.” In a kind of poetic justice (for her if not for them), these children, Elizabeth, aged 8, and John, 6, accompanied her on the four-month voyage. Sarah came from somewhere “near Birmingham” and her daughter’s birth was registered in 1845 in that town.

In the first half of the 19th century, some 13,000 women were sent to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), mostly for “petty theft, particularly property crimes against domestic employers.”[4] Sarah Hornsey arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on the ship Duchess of Northumberland on 21 April 1853, together with 218 other women. This was the final shipment of female convicts, and the second-to-last convict ship, ever. Changing circumstances and attitudes, both in Britain and Australia, were making it a less attractive method of punishment.

The dreadful conditions aboard an earlier voyage of Duchess of Northumberland are described below. Bear in mind that the passengers on this 1831 voyage were voluntary emigrants with passage assisted by the government, not convicts.

For many the conditions on board ship were almost intolerable, the women had access to water closets (toilets) but the male passengers had to use the upper decks for their daily ablutions. Many passengers were too afraid to take the recommended daily exercise above the decks, which compounded the claustrophobic conditions below decks. This along with the necessity to batten down the hatches and leave passengers below during days of relentless storms also caused many health problems.[5]

In general, women were better treated on the voyage than men, due primarily to concerns about mutiny by the male convicts which led them to be confined in overcrowded conditions for most of the journey.[6] A journal was kept of part of Sarah Hornsey’s voyage by the Purser of the Duchess of Northumberland, Gilbert James Inglis.[7] He recorded the arrival aboard of the convict women and their children from Millbank Penitentiary on 16 November 1852, looking “in very good condition.” He also noted the women’s excitement at having each other’s company after their separate confinements in Millbank: “After they had done their tea, they were all sent below and locked up for the night where they kept up the dancing, singing and occasionally fighting till the morning.” They sailed from Woolwich on 27 November, and the revelry soon gave way to mass seasickness as the ship sailed through a stormy English Channel. Inglis records unruly women being sent to “the box,” a confinement cell “about six feet high by about two feet square just so as they can stand upright in it.” Sarah Hornsey seems to have had as good a voyage as the circumstances permitted, neither being confined to the box nor being admitted to the ship’s hospital.

At 38, Sarah was older than the typical female convict, and her skills as a dressmaker were greater than most of her companions. Thanks to the British Government’s fine recordkeeping,[8] it isn’t too hard to imagine the short, red-haired woman as she emerged from the gloom below-decks and stepped onto the foreign shore of Van Diemen’s Land.

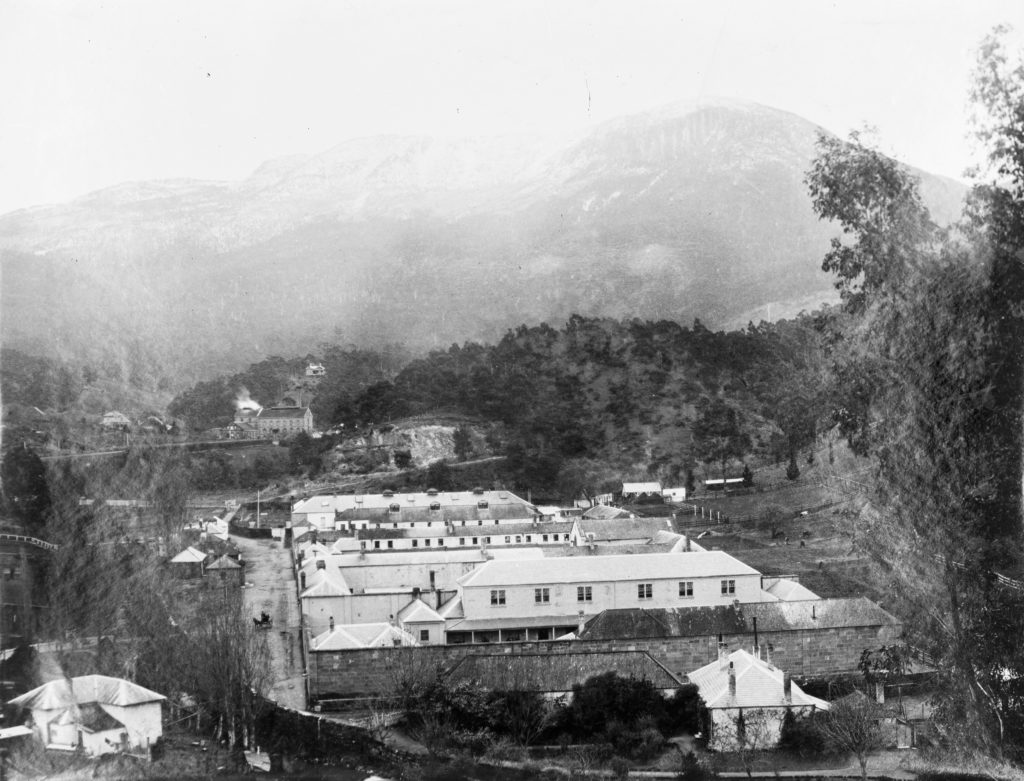

Sarah spent at least some of her time at the infamous Cascades Female Factory on the outskirts of Hobart (see photo). Her children, Elizabeth and John, were placed in Queens Orphan School. Together with three other similar institutions, these Female Factories served the combined purposes of nursery (with appalling infant mortality rates), prison, workhouse, and hospital. As the name suggests, they were intended to support themselves through the fruits of the convicts’ labours. Located in a valley and next to the flood-prone Hobart Rivulet, Cascades was damp, dreary and overcrowded. At the time, these unpleasant places with humiliating punishments and overcrowded conditions were thought to represent the most up-to-date ideas of penal design.[9] Sarah’s hard labour probably took the form of laundry or similar contract work within the Factory as part of the so-called “crime class.” Short periods of external employment on her record indicate periods of promotion to the “assignment class” between punishments.

Her detailed personal file recorded her services as a convict (mostly domestic help; she listed her trades as dressmaker and servant), as well as her misdemeanours. These were many. Sarah Hornsey spent a good part of her first two years in Van Diemen’s Land in hard labour for a combination of absenteeism and drunkenness, both of which must have been sore temptations to a fresh convict. Hard labour in this context probably referred to service at the giant laundry tubs where the women worked long hours, often ankle-deep in water to do washing for the local community at “1s 6d per dozen.”[10] Other work included ‘oakum picking’, the stripping apart of ships’ ropes to make matting and caulking.

The popular perception of the time was that the female convicts were coarse, foul-mouthed “abandoned women”, little better than prostitutes. While some undoubtedly were hardened, violent criminals (less than 3% of the women were convicted for violent crimes), the majority appear to have been disadvantaged ordinary women trying to make the best of a bad situation. It should also be recognised that the female convicts were under the authority of middle-class men to whom any working-class woman was a far cry from the refined ladies to whom they were accustomed.

Sarah was granted a ‘ticket of leave’ on 27 November 1855, which permitted her to leave custody, provided she remained within a prescribed geographical region. There seems to have been some confusion about whether Sarah was married when she left England (where the term might mean either a formal or common-law partnership). In one place it first listed her as “single, 2 children”, and then later in the same paragraph as “married two children on board”. In another document, “S” for single was scratched out and “M” for married inserted, along with the names of her children. The name “Frederick Webb” appeared below this, suggesting he was their father. However, the list of family members on the same document (her mother and brothers and sisters) also appeared to include a husband, George.[11]

Either way, she married one Joseph Helps on 7 August 1856 in the village of Hamilton, about 70 km northwest of Hobart. Amongst the convicts, transportation was generally considered to dissolve previous marriages, and the legal system typically did not inquire too closely about previous spouses.

Joseph was a ‘lifer,’ convicted for burglary in March 1843 at the age of 26 and arriving at Norfolk Island a year later. His trade is listed as ‘labourer,’ and he was assigned to duties in the hospital yard and to the survey department. He appears to have been quite the ruffian, with a litany of offences including loitering on his way to work, use of improper language to the assistant overseer, insolence, absence without leave, and refusal to work. Among his other offences, he was found guilty of “improperly apprehending a female + leaving her in a shepherd’s hut,” for which he got three months’ hard labour. It is an interesting comparison of values that Sarah Hornsey received the same sentence for being drunk.

Marriage was thought to promote good conduct, especially in male convicts, and so was encouraged by the authorities. The couple’s married life together was, however, destined to be brief. Only three months after their wedding, Joseph was in trouble again. He appeared before the New Norfolk assizes on 12 January 1857 charged with stealing two sheep, valued at £1.[12]

Hamilton constable John Smith testified that he saw Joseph Helps entering the village carrying a sack on his back, late on the moonlit night of 10 November 1856. He was in the company of another man, Michael Donaghue.[13] They were apparently coming from the direction of the Lawrenny Estate, a huge sheep farm owned by a prominent landowner Edward Lord.[14] Donaghue was seen to hide the sack in some rushes before the pair headed for their homes. This evidence was corroborated by two other constables, John Griffiths and George Aston. When the constables investigated, they found the still-warm carcass of a sheep in the bag and bloody knives in the men’s pockets. The estate manager, David Hood, testified that sheep marked like those had never been sold. The witnesses were “severely cross-examined,” and after some deliberation the jury found Helps and Donaghue guilty of sheep stealing. They were sentenced to fourteen years penal servitude in the grim and remote Port Arthur penitentiary.

Shortly thereafter, Sarah’s record indicated one last, perhaps understandable, bout of drunkenness before she received her conditional pardon on 14 July 1857. The final entry in Joseph Helps’s convict file recorded his death in Port Arthur on 26 June 1858. Sarah would have had 48 hours to claim his body, a tall order given the remoteness of Port Arthur. It is likely therefore that the prison authorities disposed of his remains.

Sarah regained custody of her children, Elizabeth and John,[15] from Queens orphan School on 12 January 1858. In 1869, her daughter Elizabeth married a man twenty years her senior named George Hayton from the community of Sorell. One of the few glimpses of Sarah’s later life comes in 1874 when George appeared in court charged with selling meat without a license.[16] The police, acting on information received, employed one Ann Jones to go and purchase the meat from George’s house which, after several attempts, she did. George pleaded innocence because he was at work and could not have sold any meat. Mrs. Jones explained how she had bought a “forequarter of mutton,” paying “old Mrs. Hornsey”, that is Sarah, while “young Mrs. Hornsey,” Elizabeth, went to write the receipt. The court concluded that it was “immaterial whether the meat was actually sold by defendant or his servants,” so George was fined £2, with an additional 10 shillings 6 pence for costs. The license would have been 5 shillings!

Sarah remained in Tasmania, where she died on 27 January 1901, aged 86. The local newspaper mentioned that the funeral procession would depart from her daughter’s house on Macquarie Street,[17] just a short distance down the street from the Cascades Female Factory.

[1] Sentences in multiples of seven years were the norm. In the event, she served less than half of this sentence before receiving her conditional pardon.

[2] Northampton Mercury, 23 February 1850.

[3] Northampton Mercury, 21 December 1850. This article was inconsistent about what was actually stolen. At one point the shop assistant was said to have missed “seven yards of print,” but then the article mentioned one, and later two, print dresses. Although Elizabeth Wright and Hannah Burgess were acquitted of this particular theft, they were convicted of others and were sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment and transportation, respectively.

[4] E.C. Casella (2001), “To watch or restrain: female convict prisons in 19th-century Tasmania,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 5, no.1 (2001), 45-72.

[5] https://bound-for-south-australia.collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/1839DuchessOfNorthumberland.htm

[6] See Tony Rayner, Female Factory, Female Convicts: the story of the more than 13,000 women exiled from Britain to Van Dieman's Land (Dover, Tasmania: Esperance Press, 2004).

[7] Transcribed in The Last Ladies, by Christine Woods, 2004 (ISBN 0 646 43073 4).

[8] And the efforts of the Tasmanian Government to digitise the original convict records. Sarah is described as 5 feet two-and-a-half inches tall, with a fresh complexion, red hair, freckles, and hazel eyes.

[9] Casella, “To watch or restrain.”

[10] Female Factory, Female Convicts, quoting an 1851 account of a visit to Cascades by Col. G. Mundy. At the time there were 730 women and 130 children in residence.

[11] The recording clerk seems error-prone because he also enters Sarah’s height in the column concerning her ability to read and write.

[12] Colonial Times (Hobart, Tasmania), 15 January 1857, 3.

[13] Convict labourers made up a large proportion of Hamilton’s population at the time. They built the Old Schoolhouse and other buildings still standing. Although there appears to have been no convict with the name Michael Donaghue, two convicts named Michael Donohue are recorded. Ironically both were transported from Ireland for sheep stealing. The record of one of these shows a pardon in December 1854 with another, later conviction; it is possible that this man was Joseph Helps’s partner in crime.

[14] Edward Lord was a former officer in the marines who had arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1804 and had built the first private house in Hobart Town. He received land grants totalling many thousands of acres, both in Van Diemen’s Land and Australia. In the mid 1820s Lawrenny consisted of around 10,000 acres, supporting thousands of sheep and cattle. Lord was one of the richest men in the colony, even though he spent much of his time in England.

[15] Elizabeth c.1846 – 1923. John c.1848 – 1918 (The Last Ladies op. cit.)

[16] The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania), Monday 13 April 1874, 3.

[17] The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania), Monday 28 January 1901, 1.