In his teaching notes collected by his students under the title Mind, Self, Society (posthumously published in 1943), George Herbert Mead argues that the “self” is not a given. Instead, the “self” emerges. He wrote for example “The social creativity of the emergent self” (1972: 214). From this perspective, the “self” is the product or the manifestation of “me”, but a phenomenon emerging from and within a set of social relations. The communication with others through participation allows for the organization and the emergence of a “self”:

This participation is made possible through the type of communication which the human animal is able to carry out—a type of communication distinguished from that which takes place among other forms which have not this principle in their societies. (Ibid.: 215)

Even though Mead is suggesting there is a fundamental difference between human communication and other forms of communication, an example drawn for the kingdom of animals can help us illustrate his main argument.

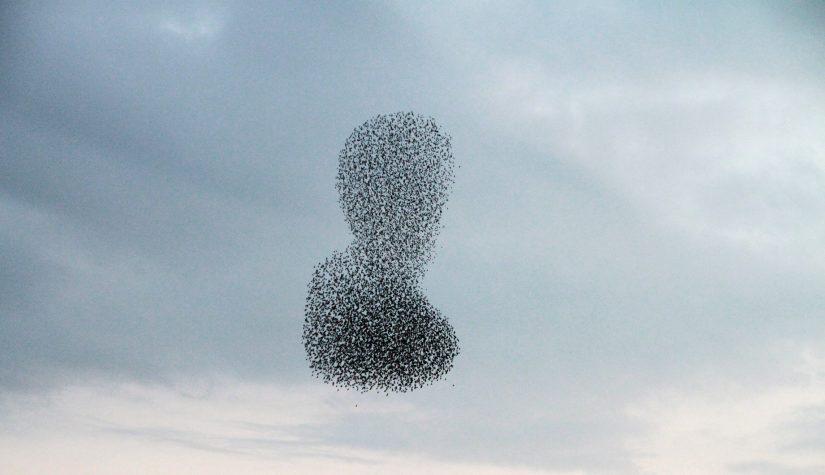

Let’s take a flock of fish, a reindeer herd or a flock of birds flying in dynamic and polymorphous formation. Clearly, the entire group manifest a degree of cohesion and organization. It actually looks and acts like a giant organism. We can track its movement, even though its form is constantly changing. Each of its members –each sardines, each reindeer, each little bird– must communicate somehow with one another if they want to stay together and not be scattered randomly in all directions. They need to communication to form a group and to participate into that group.

How is this communication taking place? Is one of the members of the flock or the herd decide for all the others? Some scientific research suggests that it may not be the case. Although there are leaders in those large groups, they do not single-handedly communicate orders and directions to the other members (Ramos, 2015). Then, is it the group as a whole –the gigantic herd of reindeer or the flock made of an innumerable number of sardines– who decide, like one single organism? Not quite so. Those flocks and herds are fluid in their behavior, constantly adapting to new stimuli from the environment (noise, smell, maybe threats from predators). This plasticity suggests the organisation of the group is not entirely predetermined nor entirely pre-established: it emerges and display characteristics and qualities that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Thus, communication does not only happen from one individual to the others, nor from the entire group to each individual. In those tree examples, communication is a process which exists and takes place between individuals. The individual’s behavior –the movement of each sardines, each reindeer, each bird– emerges in its individuality from that communication. In a way, the single sardine can be said to be an individual agent only in so far as we admit at the same time that it exists as such as the result of a complex web of relations.

Mead thus allows us to think of another communication: not as taking place from “me” to “you”, but as the process by which the experience of being “me” and being “you” can emerge. This idea of communication offers a middle ground between the idea of an agent of communication (deciding and controlling the communication process) and the opposite idea where the subject is entirely controlled by communication (think for example of the popular idea according to which “media control us”).

Along with co-author Sarah Choukah, we recently explored the implications of this emergent communication in an article written for a special issue Social Science Information: “Emergence and ontogenetics: Towards a communication without agent”. The special issue Unfolding emergence and re-animating the causal flow was edited by my colleague David Jaclin (University of Ottawa) and myself. I’ll be happy to share the article with those you make a request for it.

“Murmuration” by milo bostock (CC BY 2.0)

References

- Choukah, S., & Theophanidis, P. (2016). “Emergence and ontogenetics: Towards a communication without agent”. Social Science Information, 55(3), 286–299.

- Mead, G. H., & Morris, C. W. (1972). Mind, self, and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

- Ramos A, Petit O, Pasquaretta C, Sueur C, Ramos A, Petit O, … Longour P. (2015). “Collective decision making during group movements in European bison, Bison bonasus”. Animal Behaviour, 109, 149–160.

No related posts.

Published by

Philippe Theophanidis