ATKINSON FACULTY OF LIBERAL AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES

SCHOOL OF ANALYTIC STUDIES & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

S C I E N C E A N D T E C H N O L O G Y S T U D I E S

STS 3700B 6.0 HISTORY OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Lecture 0: Contents, Goals, Requirements

| Next | Search | Syllabus | Selected References | Home |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

Topics

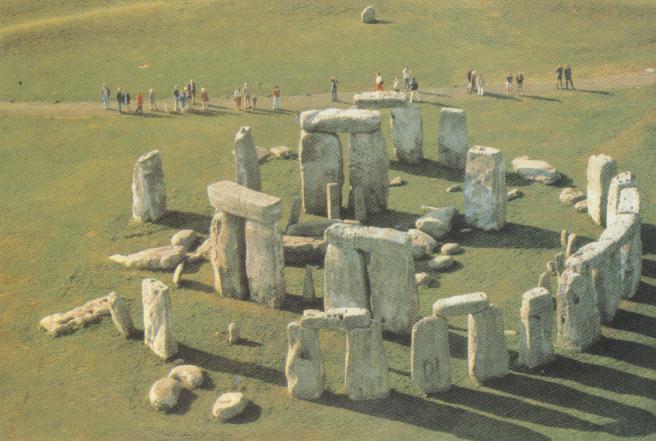

- If you read the works of Alan Turing (1912-1954), one

of the pioneers of modern computers, you will find that he often uses the word

computer in the sense of a person who carries out

computations—sometimes in his head, sometimes on paper. If we

look at human history, we discover that the need to compute, to do calculations

of various sorts, goes back as far as we can see. Even Stonehenge

(about 3000 BCE) seems to have functioned (at least in part) as an astronomical

calculator, and the origins of the abacus are lost in the mists of time.

In fact, as we shall see, the need to facilitate calculations is recorded in

the ancient history of most cultures.

Words such as to compute, computing, or computer derive from the Latin verb computare, where com signifies 'together,' 'thoroughly,' and putare signifies 'to settle (an account),' 'to reckon.' [The New Shorter Oxford Dictionary. Oxford 1993] The concept of computing, however, reaches much farther back in time, and much further out in space than ancient Rome. Something similar can be said of the word information, which also derives from a Latin verb: informare, and signifies 'to shape,' 'to form an idea of.' [op. cit.]

- The modern computer did not simply spring out of nothing sometime in the

first half of the 20th century. It has a rich and long history, which is likely

to be ignored or forgotten, if we only pay attention to modern hardware.

This history bears witness to a deeply rooted human propensity to simplify the

store of our experience, to quantify and manipulate it, to make predictions.

Like biological evolution, each stage in this history constrains, to some

extent, further developments, and must therefore be studied carefully, if we

want to understand why we are where we are today.

Stonehenge

- The course will thus begin with a necessarily brief survey of ancient

computing, from the dawn of history to the first quarter of the 19th century.

This seemingly arbitrary cut-off point makes sense if we notice that in the

1830s Charles Babbage (1791-1871) began designing the

Analytical Engine, which, as we shall see, represents the first

computer in the modern sense of the term. Babbage's invention was soon

forgotten, however, and the remainder of the 19th century is relatively

uneventful for our purposes. The year 1900 marks a crucial turning point

in the history of computing. In that year David Hilbert

(1862-1943), one of the greatest mathematicians of all times, delivered

a famous lecture, The Problems of Mathematics, at the Second

International Congress of Mathematicians in Paris. In that lecture Hilbert

posed many questions concerning the theoretical limits of computation.

I want to quote directly from Hilbert's lecture, because what he says

clearly explains why an historical perspective is so important even in science.

"History teaches the continuity of the development of science. We know that every age has its own problems, which the following age either solves or casts aside as profitless and replaces by new ones. If we would obtain an idea of the probable development of mathematical knowledge in the immediate future, we must let the unsettled questions pass before our minds and look over the problems which the science of today sets and whose solution we expect from the future. To such a review of problems the present day, lying at the meeting of the centuries, seems to me well adapted. For the close of a great epoch not only invites us to look back into the past but also directs our thoughts to the unknown future.

"The deep significance of certain problems for the advance of mathematical science in general and the important role which they play in the work of the individual investigator are not to be denied. As long as a branch of science offers an abundance of problems, it is alive. A lack of problems foreshadows extinction or the cessation of independent development. Just as every human undertaking pursues certain objects, so also mathematical research requires its problems...

"It is difficult and often impossible to judge the value of a problem correctly in advance; for the final award depends upon the gain which science obtains from the problem. Nevertheless we can ask whether there are general criteria which mark a good mathematical problem. An old French mathematician said: 'A mathematical theory is not to be considered complete until you have made it so clear that you can explain it to the first man whom you meet on the street.'

" - Hilbert's lecture sparked a great flurry of research, and the history of the answers to some of his questions leads directly to the development of the modern computer towards the end of the first half of the century. The study of this exciting period will also prompt us to examine the broader context—social, economic and political—in which the computer developed. We will examine, in particular, the role that WWII had on accelerating such development, and the surprising shift from computation to information, which eventually led to the internet.

- The third and final part of the course will explore the world ushered by the modern computer, its successes and its problems. The often inflated promises of artificial intelligence, the profound changes in what has become known as the global information society, the phenomenon of the Internet and the web, the hot, new issues about electronic commerce and trade, education, property rights, privacy, freedom and censorship, security, etc.

- The course will end with a brief review of the tortuous path we have followed, and a summary of the main conclusions and of the many issues which are still unresolved.

Readings and Resources

- Given the range and variety of the material we will be studying,

there is no required textbook. Throughout the course, live links to

on-line readings, as well as references to off-line material will

be provided. Many are simply presented as suggestions. Some are required reading,

and are specially marked with a red arrow

- I have set up a discussion list, and all the students registered in the course have been subscribed to it. To send mail to the list use the following address: STS3700B-List@yorku.ca. The list is exclusively for academic matters directly related to this course.

- You are strongly encouraged to spend time in the York Libraries, or in any other good library close to you. If you live or work in downtown Toronto, you can also use the Metro Reference Library, the Ryerson Library, the University of Toronto Libraries, etc. Library holdings do not consist of books only. There are scholarly journals and good and reliable magazines. I strongly urge you to physically go to a library and explore. At least for the time being, libraries are still the essential tool for scholarship—they have not been supplanted by the internet.

- Finally, even if you are an experienced web surfer, please

read

Effective Internet Search Strategies. This is a

very useful summary of good search practices on the net.

Effective Internet Search Strategies. This is a

very useful summary of good search practices on the net.

Picture Credits: University of Virginia

Last Modification Date: 11 April 2003