U n i v e r s i t é Y O R K U n i v e r s i t y

ATKINSON FACULTY OF LIBERAL AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES

SCHOOL OF ANALYTIC STUDIES & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

S C I E N C E A N D T E C H N O L O G Y S T U D I E S

STS 3700B 6.0 HISTORY OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

ATKINSON FACULTY OF LIBERAL AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES

SCHOOL OF ANALYTIC STUDIES & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

S C I E N C E A N D T E C H N O L O G Y S T U D I E S

STS 3700B 6.0 HISTORY OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Lecture 8: The Middle Ages II

| Prev | Next | Search | Syllabus | Selected References | Home |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

Topics

-

Here is a brief timeline

spanning the period considered in this lecture:

spanning the period considered in this lecture:

- ca 800: Chinese start to use a zero, probably introduced from India

- ca 850: Al-Khowarizmi publishes his Arithmetic

- ca 1000: Gerbert d’Aurillac describes an abacus using apices

- 1120: Adelard of Bath publishes Dixit Algorismi, his translation of Al-Khowarizmi's Arithmetic

- 1200: First minted jetons appear in Italy

- 1202: Fibonacci publishes his Liber Abaci

- 1220: Alexander De Villa Dei publishes Carmen de Algorismo

- 1250: Sacrobosco publishes his Algorismus Vulgaris

- ca 1300: Modern wire-and-bead abacus replaces the older Chinese calculating rods

- 1542: Robert Recorde publishes his English-language book on arithmetic

-

As we have already seen, probably the most important contribution to the development of the science and technology

of computing in the Middle Ages comes from the Arab world, beginning in earnest in the tenth and eleventh centuries,

with important events dating back to at least the ninth century (e.g. Al-Khwarizmi, ca 780 - 850). Geographically,

the focal points of this influence were southern Italy and Spain, where a remarkably peaceful coexistence formed

among Christians, Jews and Muslims. Al-Khwarizmi's works, in particular his book on algebra, Hisab al-jabr w'al-muqabala,

became very popular among scholars, also because they aimed at tackling real-world problems (incidentally, the word

"algorism" became well established in Europe to indicate the new techniques for computing, especially on

the abacus). Consider for instance, Mohammad Abu'l-Wafa Al-Buzjani's

book entitled Book on What is Necessary from the Science of Arithmetic for Scribes and Businessmen.

In the introduction, he write that the book

"comprises all that an experienced or novice, subordinate or chief in arithmetic needs to know, the art of civil servants, the employment of land taxes and all kinds of business needed in administrations, proportions, multiplication, division, measurements, land taxes, distribution, exchange and all other practices used by various categories of men for doing business and which are useful to them in their daily life."

For a good reference to the history of computing in business, read J W Durham's survey article Introduction of Arabic Numerals in Western Accounting. -

The abacus was the main computational device in the Middle Ages—it was the computer of this period.

It is interesting to note that

"Whether in the Italian double-entry, English Exchequer, or in other systems, Western European commercial records of the Middle Ages almost uniformly use Roman numeric notation until the fifteenth century […] The notation was in its time both effective and efficient–indeed […] superior in some respects to Arabic numeration. Roman notation was probably introduced to most medieval schoolchildren early in their education. In understanding the role of Roman numerals, it is essential to understand that their effective usage was bound up with the use of the abacus. The abacus was the primary calculating device of the Middle Ages of Western Europe. The medieval commercial abacus had several variants, ranging from the large surface used in the English Exchequer to the more common 'lines' form apparently derived directly from the abaci of classical antiquity."

Although, formally speaking, the positional system of numbers (with the zero), was only introduced in the late Middle Ages, even the ancient abacus already embodied it.

[from Introduction of Arabic Numerals in Western Accounting]"The essential principle of the abacus (in any form) is that of place-value notation […] The Roman numerals are closely bound to the abacus. In the abacus, a token (bead, counter, or even a simple impression in a sand-covered table) derives its value from its location in a column or on a line. Arithmetic is made possible by two place-value rules:

- numbers are represented by the number of tokens in a place-value location;

- a place-value location can only contain a specified maximum number of tokens.

Gerbert d’Aurillac (ca 940 - 1003) (Pope Sylvester II)

-

This system would become more and more complicated as the operations to be performed included multiplications and divisions, particularly

with large numbers. To obviate these difficulties, in the tenth century Gerbert d’Aurillac (ca 940 - 1003), who became pope Sylvester II, the

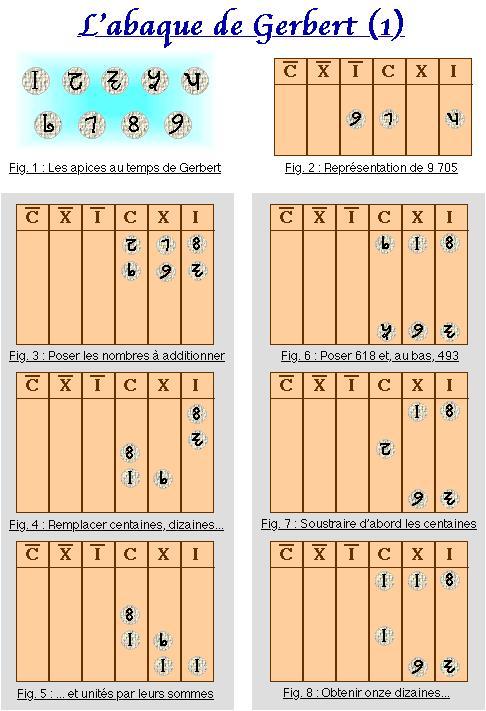

first French pope, introduced the Indian-Arabic number system, and an abacus that used apices, i.e. counters, each with an arabic digit

inscribed on it. Although many scholars welcomed the new notation (which was much more suitable to written calculations—which the

introduction of paper had made more practical—general acceptance did not follow—in fact, long controversies (sometimes even of a

religious nature) ensued, and Gerbert's innovation was not generally adopted until the fifteenth century. [see, for example,

Le Super-Abaque de Gerbert]

Gerbert d’Aurillac's Super Abacus

The apex or numbered counter, allowed the replacement of the many tokens (pebbles, beads or calculi) in each column, by single counter, which represented the number of tokens. In other words, it was now possible to represent any number, no matter how large, using only ten symbols, one of which represented… nothing. It was zero. This simplification was accompanied by an outburst of new and more effective computational techniques (algorithms), thanks also to appearance in Europe of the translations of many of the ancient Greek and Arabic texts. One of the most important figures of this time was the philosopher Adelard of Bath (1075 - 1160), who "made the first wholesale conversion of Arabo-Greek learning from Arabic into Latin," translating many texts, from Euclid to al-Khwarizmi. -

One of the great contributors to the art and science of calculations on the abacus was Leonardo Pisano Fibonacci (ca 1170 - 1250).

Here is his own account of the origins of his interest in this device:

"When my father, who had been appointed by his country [The Republic of Pisa] as public notary in the customs at Bugia [Algeria] acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians' nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it, for whatever was studied by the art in Egypt, Syria, Greece, Sicily and Provence, in all its various forms."

Fibonacci wrote several books: Liber Abaci (1202), Practica Geometriae (1220), Flos (1225), Liber Quadratorum, and a book on commercial arithmetic, Di Minor Guisa, unfortunately lost. Notice the use of the Italian in the last title. Fibonacci became very well known in his lifetime, although it was " the practical applications rather than the abstract theorems that made him famous to his contemporaries." Read Kevin Devlin's The 800th Birthday of the Book that Brought Numbers to the West.

In Flos, Fibonacci considered the problem of finding an approximation of one of the roots of 10x + 2x2 + x3 = 20,

"one of the problems that he was challenged to solve by Johannes of Palermo. This problem was not made up by Johannes of Palermo, rather he took it from

Omar Khayyam's algebra book where it is solved by means of the intersection a circle and a hyperbola. Fibonacci proves that the root of the equation is neither

an integer nor a fraction, nor the square root of a fraction […] Without explaining his methods, Fibonacci then gives the approximate solution

[…] as 1 + 22/60 + 7/602 + 42/603 + … This converts to the decimal 1.3688081075, which is correct to nine decimal places,

a remarkable achievement." [ op. cit. ]

Fibonacci must be considered one of the major developers of number theory, even though his mathematical (as opposed to applied) work remained essentially

ignored and unknown until it was re-discovered until the seventeenth century.

The 800th Birthday of the Book that Brought Numbers to the West.

In Flos, Fibonacci considered the problem of finding an approximation of one of the roots of 10x + 2x2 + x3 = 20,

"one of the problems that he was challenged to solve by Johannes of Palermo. This problem was not made up by Johannes of Palermo, rather he took it from

Omar Khayyam's algebra book where it is solved by means of the intersection a circle and a hyperbola. Fibonacci proves that the root of the equation is neither

an integer nor a fraction, nor the square root of a fraction […] Without explaining his methods, Fibonacci then gives the approximate solution

[…] as 1 + 22/60 + 7/602 + 42/603 + … This converts to the decimal 1.3688081075, which is correct to nine decimal places,

a remarkable achievement." [ op. cit. ]

Fibonacci must be considered one of the major developers of number theory, even though his mathematical (as opposed to applied) work remained essentially

ignored and unknown until it was re-discovered until the seventeenth century.

"Direct influence was exerted only by those portions of the Liber Abaci and of the Practica that served to introduce Indian-Arabic numerals and methods and contributed to the mastering of the problems of daily life. Here Fibonacci became the teacher of the masters of computation and of the surveyors, as one learns from the Summa of Luca Pacioli…"

-

A figure we must mention, because of the significant scientific intuitions he had, as well as because of his work in mathematics and the natural sciences,

is Roger Bacon (1214 - 1294). One of his famous

statements, "mathematics is the door and the key to the sciences" anticipates Galileo's "the book of nature is written in the language of

mathematics." Bacon's most important work was in the application of geometry to optics. He was probably the first to propose the telescope:

"For we can so shape transparent bodies, and arrange them in such a way with respect to our sight and objects of vision, that the rays will be reflected and bent in any direction we desire, and under any angle we wish, we may see the object near or at a distance […] So we might also cause the Sun, Moon and stars in appearance to descend here below…" [ op. cit. ]

Notice that, if we considers lenses as devices for magnifying objects alreay visible to the naked eye, then this history, not of the telescope, but of magnifying lenses goes back to the Egyptians and the Greeks:- "Egyptian artifacts include rock crystals in the from of convex lenses (~2600 B.C.E.)

- The Greeks and Romans continued with these types of lenses up to the end of the Roman Empire (~31 C.E.)

- Knew and practiced the art of glass blowing

- Observed that objects placed in a bulb filled with water appeared magnified"

[ from The Paper Project: A New Light on Paper ] Bacon also started an ambitious encyclopaedia of all the sciences, a proposal for which was approved by pope Clement IV in 1266, despite the strong opposition of Bacon's religious superiors, which forced Bacon to work on the project in secret. "Bacon was aiming to show the Pope that sciences had a rightful role in the university curriculum." The project was never completed, mainly due to the death of the pope, but three books remain: "Opus Maius (The Great Work), Opus Minus (The Smaller Work) and Opus Tertium (The Third Work)." -

Although this work, according to our definition of the Middle Ages, does not quite fall within this period, I will finish this lecture

by mentioning The Ground of Artes ("…teaching the perfect work and practice of Arithmeticke etc."), published in 1543

by Robert Recorde (1510 - 1558).

"…he did this with a very deliberate policy in mind. Firstly he wanted to produce a complete course of mathematical instruction and he wrote his books in the order in which he thought that they should be studied in a mathematics course. It was a course of study which he wanted to be available to everyone, not just the few educated men who could read Latin or Greek. He therefore wrote all his books in English…" [ op cit ]

Recorde was also the inventor of the 'equals' symbol '=', which "appears in Recorde's book The Whetstone of Witte published in 1557. He justifies using two parallel line segments: 'bicause noe 2 thynges can be moare equalle'. The symbol = was not immediately popular. The symbol || was used by some and æ ( or œ), from the word 'aequalis' meaning equal, was widely used into the 1700s."

Readings, Resources and Questions

- The cases of Fibonacci and Bacon seem to show that the engine powering the development of science is sometimes external to science itself. Discuss.

© Copyright Luigi M Bianchi 2001, 2002, 2003

Picture Credits: DefiMath Mathadore · Un Zest d'Auvergne

Last Modification Date: 25 September 2006

Picture Credits: DefiMath Mathadore · Un Zest d'Auvergne

Last Modification Date: 25 September 2006