February 14, 2022

By Christina Love (Undergraduate Student, Indigenous Studies and French)

Christina Love is a contributor to the GLRC’s interview series entitled Workers’ Stories in the COVID-19 Era. She was also a union organizer with Workers United at her local Shoppers Drug Mart from October 2020 – February 2021. A staunch labour and human rights activist, Christina has been involved in her local community, politics, and the YorkU community since starting university. Formerly the Director of Public Relations for the Palestine Solidarity Collective at York, a candidate in the 2021 federal election, and the current President of OPIRG York, Christina seeks to do what she can when she can. We all deserve better.

Introduction

Organizing is a loaded word. What is an organizer? While what it means to be an organizer is debatable, for me, organizers do the following: engage their community/communities and try to advocate for change. They put their values into concrete actions.

My relationship to labour organizing is one that starts with injustice. I could go on and on about theories of poverty and the working classes, but it is an entirely different matter to actually live it. It’s incredibly hard to break free of the machine I was born in and have lived within my whole life.

Background

Growing up for me was marked by the complicated existence of being poor in Canada. Looking at where and how I grew up means looking at the fact that I live in the suburbs, grew up in the 2000s and 2010s, and am a white, able-bodied woman. Like many in my situation, my relationship with poverty is one marked by familial trauma and mental illness. From almost going bankrupt and becoming homeless, to the complications of depression, to the necessity of having 24-hour care for some family members, there are hidden costs to being poor that we don’t often think about. Even so, having resources like a grandfather who did his best to help when he was still alive, and a mom with a stable income, gave us advantages that so many other poor folks just don’t have.

Growing up for me was marked by the complicated existence of being poor in Canada.

When I think of poverty and my younger years, I think, Why? Why were things like that? Why are they still like that? My activism and beliefs are rooted in my own experiences, and compassion for others who experience oppression. This is the backdrop against which I built my beliefs about labour into real action.

Setting the Scene

From the age of 12 I’ve had various jobs because I knew that it was up to me to fund my post-secondary education. Initially, this meant having a paper route and doing babysitting and dog walking. Once I was 16, I got my first formal part-time job as a cashier at a local Shoppers Drug Mart. Looking back, they took advantage of my desperation for employment from the start. They encouraged me and my coworkers to stay late and made us work irregular hours. They also allowed customers to abuse staff, did not compensate us fairly, discouraged breaks, etc. The COVID-19 pandemic brought these, and new, issues to a head.

I have never been worse abused by other people than I have been working retail during the pandemic. I would like to bold, underline, and highlight that. When people are pushed to breaking points due to forces outside of their control, they will often lash out at those who are devalued in society. In this context, this has meant a sharp increase in violence against workers. From the standpoint of employers, this pandemic brought about an opportunity to prey on people’s increased vulnerability and further profit off of exploiting them.

I have never been worse abused by other people than I have been working retail during the pandemic.

At the beginning of the pandemic, not too much changed. We didn’t have to start wearing masks until that summer and there were no plastic dividers or anything like that yet. It was mostly just a slight increase in wiping down high contact surfaces and product shortages. We also got a $2 wage subsidy from Loblaws Companies Ltd., which was much needed for those of us working minimum (and unlivable) wage jobs. As the pandemic progressed, however, our duties increased drastically and any support we got at the beginning petered out.

Some of the things cashiers were now expected to do, in my location at least, were to wipe surfaces after each customer, enforce distancing and mask-wearing, answer pharmacy calls, and monitor store capacity. This was in addition to our regular tasks of stocking and tagging shelves, checking for product expiries, cashing out customers, answering customer service calls, and responding to inquiries. In March of 2020, I also started working in the post office as well since one of the full-time workers was going on maternity leave. The most concise way I could describe this experience is hellish. As a part-time worker, I had to rapidly learn all the post office paperwork, the various systems and services we offered, and deal with twice the traffic with half the staff. Understaffing was a constant issue on all fronts during the entire pandemic. It wasn’t as though there weren’t people who wanted to work—there were—but staffing was cut for ‘capacity reasons.’ This is despite the fact that we had the same amount, if not more, customers in the store. In short, it was a money-grab at the expense of the workers.

The most concise way I could describe this experience is hellish.

One of the worst aspects about working during the pandemic was the abuse workers were getting from the customers. We had people endlessly complaining about the restrictions, refusing to mask and distance, lambasting employees for product shortages as if we were personally responsible, and so much more. One of the worst things that I experienced was a person who came into the store to access the post office. When I notified them that we were closed and the website did not have an updated closing time, they proceeded to scream at me, calling me a lying bitch who was just a lazy asshole and didn’t want to serve them, among worse things. They did this for around seven or so minutes and I was afraid they were going to get behind the counter and hit me at one point. I called a manager, but in a classic managerial move, they didn’t arrive until after this person left. We didn’t yet have the mall security number posted and I was hesitant to call 911. Instances similar to these were almost a daily experience at this point, and that $2 wage subsidy ended three months in.

Precarity rose significantly in retail during the pandemic. Our week-by-week schedules now got less reliable, and hours madly fluctuated. I might’ve worked 37 hours one week and eight the next. Towards the end, I was barely getting five hours a week. Contributing to this precarity was the lack of paid sick leave. Not only did we have to arrange our own coverage if we were sick, but we’d be missing out on pay, so some people would just come in feeling unwell. When you are desperate, choices aren’t treated as rights, so much as luxuries.

When you are desperate, choices aren’t treated as rights, so much as luxuries.

Management was horrific during this all. Not only did they allow the customers to abuse us with impunity, understaff the store, and give us a large number of new tasks outside of the scope of our positions, but they also implemented COVID protocols with about as much care as Doug Ford gives to human rights. Off the bat, there were no options for curbside pickup, so anyone who medically could not wear a mask was forced to come into the store at greater risk to themselves and others. This also meant a decrease in workplace safety since we could not refuse service to anyone who could not, or would not, wear a mask and direct them to an appropriate accommodation. Furthermore, the Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS) was disregarded entirely with regards to the unlabelled cleaning chemicals we were using to disinfect high touch areas. Not only did we not know what was in these cleaners, but as the store gradually got restocks of regulated cleaners, they were all sold off rather than having a supply reserved for store use. We had no one at the doors ensuring proper masking prior to entry, nor did we have a designated staff person to monitor store capacity limits; this would fall on the cashiers and supervisors and many times things would slip through the cracks. To put candles on the cake, no one was notified if a staff member or customer tested positive for COVID. Public Health or the people themselves would notify management, but not one of us workers would be briefed and offered testing.

All of this compounded into constant frustration and mental strain. I genuinely didn’t know how I was going to get through the day most of the time. I felt like a robot; I was stressed, I was abused, and I lost faith in almost everything. I am not one to complain without at least trying to do something, though, so I decided to go for broke and attempt to unionize. Being a part-time worker with some savings, and who could likely find different work if unionization didn’t pan out, put me in a position of not caring about losing my job anymore.

I am not one to complain without at least trying to do something, though, so I decided to go for broke and attempt to unionize.

Initial Contact

In September of 2020, I began to research and email, which, as I soon found out, is a surprising amount of what labour organizing entails. I looked into the different unions and a bit into the history of the labour movement in Canada. I then emailed the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Toronto, United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), and Workers United to ask about unionizing. A CUPE representative got back to me rather quickly saying that they didn’t organize retail. IWW didn’t get back to me until about two months later, at which point I had already been in talks with reps from UFCW and Workers United.

From phone calls and emailing back and forth, I decided to pursue unionization with Workers United because they seemed to be a more democratic union. I then met a rep at a local Tim Horton’s and discussed the ins and outs of unionizing, including what to expect in terms of pushback should the managers or owner find out about it.

How to Organize a Union

Step 1: Research the history of unionization, what benefits union-members experience, and options in terms of local unions; and list out the reasons why you want to unionize. Such extensive research isn’t strictly necessary, but it helps with resolving your thoughts and really getting committed to the work you’re about to do. I think that this is important since half-hearted organizing is generally unproductive.

Step 2: Contact a bunch of different unions in your sector and talk with different reps. Get a good grasp of the differences between unions and what resources they provide you with as an organizer.

Step 3: Connect with the union you have decided on and they will match you with a rep who will help you along the way.

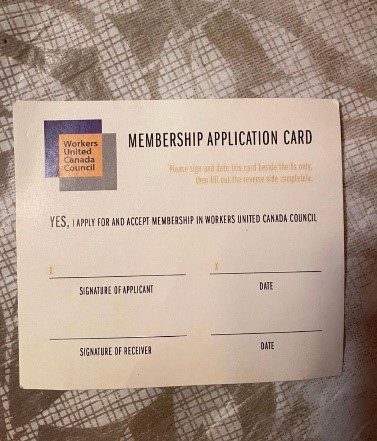

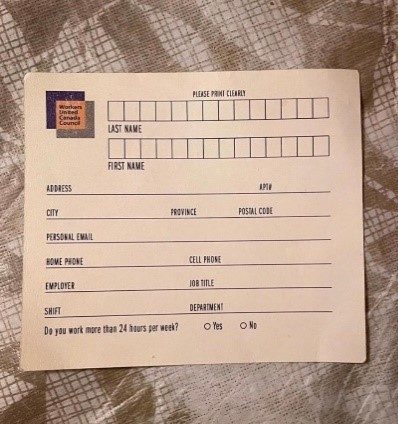

Step 4: CARD SIGNING TIIIMMMEEE! Basically, it is a legal requirement to have at least 40% of non-managerial staff sign a union card before an application to be unionized can be filed with the Labour Board; this didn’t used to exist, but labour laws have changed. This is the most difficult step since you need to talk to people and convince them to sign a card expressing their support for unionization. Ideally, you’ll get more than 60% of people to sign so that the vote is likelier to pass. To properly complete this step, you need to get an approximate gauge on the number of non-managerial workers there are. Since there were no convenient lists I could access, I got an idea of our staffing situation by taking discreet pictures of the logbook and schedules.

Step 5 (I didn’t get this far): An application to be unionized will be filed by your union rep with the Labour Board. At this point, there will be a week’s processing time and the employer will receive notice that their staff wants to unionize.

Step 6: The employer will be trying to spread anti-labour propaganda and instigate division between workers. You and the more passionate coworkers will be dispelling this and reaffirming the choice to unionize, especially highlighting that the bosses wouldn’t be so anxious to stop it if it was such a bad thing for the employees.

Step 7: A vote will now be held by secret ballot. In order for a union to pass, 50% plus 1 person needs to vote in favour of unionizing. The only people who can vote are the non-managerial staff, and, in the case of Shoppers Drug Mart, those who aren’t pharmacists. Once a union vote passes, everyone is unionized, not just the people who voted in favour.

Step 8: If the union vote is successful, you will now be creating a Collective Agreement (CA) outlining the terms and conditions of your employment. Essentially, its function is to act as a legal shield against the brunt of injustices that employees at your workplace are facing. A CA is negotiated through collective bargaining, which is the back-and-forth debate on terms between the union and management.

Step 9: Congrats! The Collective Agreement passed and you are now fully unionized. This means that you are legally entitled to have the CA be upheld and will begin paying union dues. From what I was told, the pay raise per hour will be more than enough to cover dues and then some. The raise you negotiate depends on the nature of your CA, which you decide. Regardless, when I was organizing, dues for Workers United were between $7 to $9 per week.

Step 10: Labour organizing does not end upon the implementation of the Collective Agreement. A democratic union is one in which the members fully participate. This means being engaged in the broader union structure, including voting and talking to your coworkers about what does and doesn’t work when the time for renegotiating the CA comes around. If you do not participate, the employer and opportunists within the union will take advantage of this, usually for financial or career benefits.

A Few Notes on Unionization

*A very common misconception is that unions themselves dictate the terms of the CA. This is untrue. While they will help with the wording and provide legal support, it is the employees that decide on the terms and conditions.

*Another misconception is that you start paying union dues immediately. This is also blatantly false. You only start paying dues (which are proportional to hours worked per week) once the CA comes into effect.

*A note on the method of unionization I chose: Though you can form a union solely of your coworkers rather than going with an established union like Workers United, you don’t have the same access to legal resources or experienced advice in that case. Moreover, you need a LOT of buy-in for this form of unionization to be impactful. Interestingly enough, IWW takes an approach to unionization in between this and conventional unionization.

My Experiences Organizing

I felt a weird mix of emotions while I was in the process of trying to unionize. On the one hand, I felt like I had this bubble of inner strength that came from knowing I was trying to change things, which made going to work easier. On the other hand, I got fairly dejected with organizing due to the responses I was receiving from some coworkers and the nature of organizing during the pandemic.

…I felt like I had this bubble of inner strength that came from knowing I was trying to change things, which made going to work easier.

Some admin issues delayed my rep from Workers United from providing me with union cards initially. I ended up receiving a stack of cards in late November/early December 2020. Prior to this, I had started to discuss unionizing with a couple of coworkers I trusted and knew would be interested. Once I got the cards, I branched out a bit more. Now, prior to COVID, union reps would themselves visit people’s houses to discuss unionization and organizing plans. However, the pandemic meant that the only direct interaction my coworkers were getting was with me, though I did provide them with the contact information of the union rep.

Finding the time to talk with people was a huge challenge. This is definitely the sort of conversation you want to have face-to-face, but I was basically just seeing people while on breaks, while in the back room cashing out, and occasionally when someone would offer to drive me home. Those drives home and catching people after work was when I was best able to discuss unionization and the implications for us if we unionized. I initially reached out to people I knew would at least be open to hearing my message, and I was largely correct. By February I had about 14 cards signed.

This is where I met a couple of roadblocks. First, I was starting to get worn out. Everyone I had talked to, while passionate about the cause, was concerned about retaliation if we were caught so I was the only one actively talking to people and getting cards signed. This caused a significant amount of burnout and slowed the process. Second, I was now beginning to talk to the more apathetic or reluctant coworkers. This posed a few issues.

You cannot make anyone see your views if they won’t even look. This means that if someone didn’t want to hear about unions, they would not hear from me. A lot of the merchandisers who weren’t very customer-facing and the employees from more privileged backgrounds were like this. Many didn’t see the point, some didn’t want to make the (marginal) effort, and others were actively anti-union. In the end, we didn’t get to the voting stage.

You cannot make anyone see your views if they won’t even look.

Final Thoughts & the Privilege of Quitting

It’s not my place to blame anyone for not wanting, or not being able, to unionize. I did the best I could and, to date, trying to unionize is the thing I am most proud of doing in my life. I made this effort because the injustices myself and so many others face need to be fought against. Who will fight if we won’t? We all deserve so much better than the status quo and unionization is one avenue we can take to decrease injustice. The labour movement has been so historically powerful because of regular people getting together and imagining a better future, then seizing the present. Our legacies lie in the actions we take and what we leave behind.

Who will fight if we won’t?

I quit my job at Shoppers on Monday, March 15, 2021. The day before, I had a shift where three anti-maskers came in and I had to call security twice because they were getting violent. I called the manager on the third anti-masker, and rather than having them wear a mask or go elsewhere, the manager proceeded to check them out in front of my station. I’d had enough of this. I went home and cried then wrote two letters of resignation. One was very harsh, and I wrote it to vent more than anything else, and the other more calmly outlined my reasons for quitting. I delivered it the next day, gave away my only shift in the next two weeks, and walked out without a backward glance. I haven’t stepped foot in that store since the day I quit.

Once I had left, there wasn’t relief so much as an emptiness where I once had ongoing pain. The scars of the trauma I’ve experienced working during the pandemic continue to impact my life, but the difference now is that if I’m in a situation where someone is abusing me, I can fight back or walk away. That is my unalienable right. Even so, I generally avoid going shopping now because I get really anxious and tense whenever I see someone indoors without a mask or someone who is abusing an employee. I can and will step in when I see something wrong happening, but there’s not much I can do about maskless people other than walk away.

Quitting was a privilege for me, especially since so many people have lost their jobs and been so desperate for work during the pandemic. I had enough saved to pay tuition for the next couple of years and with negligible expenses from living at home, and I was in an okay place to leave that job. Many are not and they need our solidarity to fight for their rights.

Poem: The Worker

Day in.

Day out.

I am no longer a person.

I have no rights.

My life is sold.

My mind is clouded.

There is no light at the end of this tunnel.

There is abolition or apathy.

– Christina Love, 2022