What do we mean by inclusivity?

By Valérie Florentin and Lianne Fisher

Valérie: After a few years spent teaching online, I felt the need to get some more education about new trends, so I took several workshops at the Teaching Commons and attended a few other pedagogy related activities outside of York. Because I’m largely interested in social justice and the role of a postsecondary education as the “great equalizer” that it was meant to be, I was already leaning towards universal design for learning (UDL), accessibility and diversity, mostly in terms of learning exceptionalities because, being neurodivergent, that’s what I know. And I thought I knew… before I realized I was wrong, and that’s when I met Lianne. What follows is short summary of our common thoughts on inclusivity, with more to come...

Universal design in education is a crucial approach that works to ensure teaching methods and environments are accessible and inclusive for all students, regardless of their abilities. However, the conversation around inclusivity often misses the mark, as current educational practices still largely favor neurotypical ways of thinking and we often fall short of truly embracing neurodiversity, which encompasses a range of neurological differences, including autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and more (see Chapman, 2023; Dolmage, 2017; Erevelles, 2011). The problem lies in the fact that our education system is still largely tailored to the neurotypical majority (Dolmage, 2017; Price, 2011). We often prioritize verbal and written communication, linear thinking, and strict adherence to rules and routines (including the mastery of academic writing). This leaves little room for the creative, non-linear, and flexible thinking often exhibited by neurodivergent students, who can be left feeling isolated, misunderstood, and unsupported in their learning journey (see cast.org; Stienstra, 2020; Tobin & Behling, 2018).

What we mean is that, of course we accommodate, but the tacit expectation is still that these measures are there to help the students reach the (neurotypical) objectives… so basically, we’re asking them to translate their thoughts into something that fits our needs. Yes, you read that right. We seriously think that we are, in fact—as a society and not just in education—adding to the cognitive load of our neurodivergent students.

Our opinion is that true inclusivity in education requires a shift in our approach to teaching and learning. It calls for a more holistic understanding of neurodiversity and an appreciation of the unique strengths and challenges that come with different ways of thinking. It should probably start by focusing on UDL to ensure that the learning goals are met, under whatever form that mastery can take, and up until now, a lot of instructors think that accepting audio or video files in lieu of the classical essay mean that we’re doing our best… we’re not. We’re offering choices, for sure, and maybe it’s enough for some, but those assignments still have to meet typical expectations (see Tobin & Behling, 2018; Quirke, McGuckin, & McCarthy, 2024).

You might think: how do we grade on content alone? How can we learn to separate the format (academic writing, “proper” presentations) from the ideas, if these are presented in a way we’re unaccustomed to? It’s a very valid question and ungrading, though imperfect, might be a part of the answer, just as asking our students to hand in their assignments in the form that’s most meaningful to them might be.

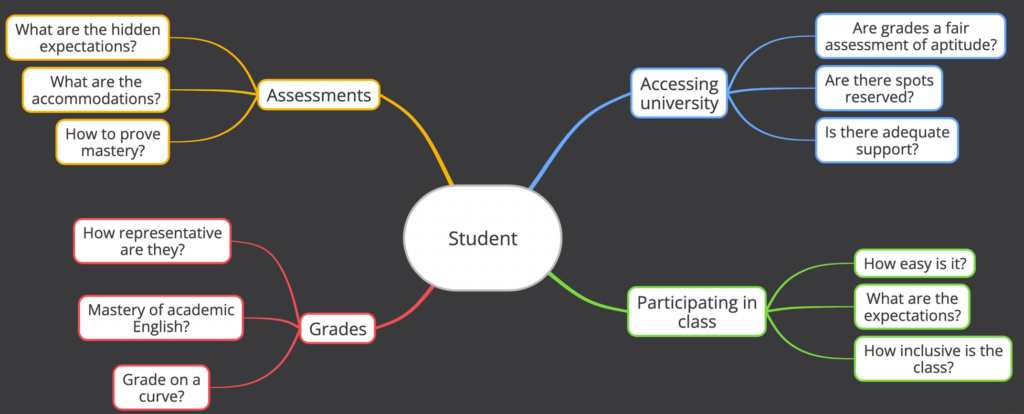

Another part of the answer lies in the fact that designing academic content through the principles of accommodation, UDL, and accessibility works at different levels. Accommodation is at the student level. A perfect course that suits all learners is not possible–accommodations for particular students will remain needed–and the design needs to be tweaked according to each class (not course, class). The fact that the design is called “universal” doesn’t mean that it’s a one size fits all and certainly doesn’t mean that implementing it from the early stages of the conception of a new course means that we’re done. Designing with UDL most certainly can support more learners more of the time: just because a perfect course cannot exist, it doesn’t mean that we stop trying. Part of inclusive pedagogy is to consider the needs of students in a particular classroom. Accessibility and UDL approaches can help in this regard, but some instructors are looking for a checklist. Although there are specific things to do for accessibility (e.g., right click on an image to add alt-text so a screen reader will read the text and describe the image, for a person who cannot see and/or discern the image), inclusive pedagogy asks that we move beyond a training and checklist approaches. As an image should allow a learner to access the same content in a different way, the instructor’s knowledge is imperative to the design: how do you represent the content in the text in a visual way? This is not just nice to have. For some learners, it’s the primary way to access course content. Hence our focus on accessibility and UDL, and the presence of a mindmap at the start of this article.

Finally, we’d like to remind you that UDL works at the course (and program) level, whereas accessibility is more at the course/institutional level. If a campus, physical or digital, is not accessible, courses designed with UDL and accommodations for individual students are of no help, so we need to reframe our perception: our students might have diverse needs, but they still made it to our classes, which is not a negligible feat...

References

Chapman, R. (2023). Empire of normality: Neurodiversity and capitalism. Pluto Press.

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press.

Erevelles, N. (2011). Disability and difference in global contexts: Enabling a transformative body politic. Palgrave MacMillan.

Price, M. (2011). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. University of Michigan Press.

Quirke, M. McGuckin, C., McCarthy, P. (2024). Adopting a UDL attitude within academia: Understanding and practicing inclusion across higher education. Routledge.

Stienstra, D. (2020). Disablity rights (2nd ed.). Fernwood.

Tobin, T. J. & Behling, K. T. (2018). Reach everyone, teaching everyone: Universal design in higher education. West Virginia University Press.

Talks & Podcasts

Hall, Z. (2023). Intersectionality, UDL, and Communities of Belonging in Higher Ed.

Moore, S. (2016). Transforming inclusive education.

Schalk, S. (2023). Black Disability Politics.

Young. S. (2014). I am not your inspiration, thank you very much.