Leading research from international team reveals shortcomings of for-profit care and provides evidence to support improved policy for vulnerable senior population.

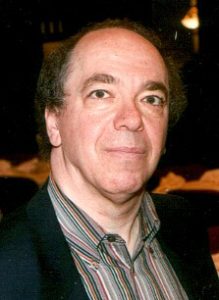

Joel Lexchin

With the aging population, new research by York University Health Professor Emeritus Joel Lexchin and others that examine the care received by clients of long-term care facilities is growing in relevance. Lexchin, also an emergency doctor at University Health Network, joined forces with researchers from the Universities of British Columbia, California and London (United Kingdom) to provide evidence that links for-profit long-term care facilities with inferior quality of care.

Pat Armstrong

The research − part of a seven-year project led by York Sociology Professor Pat Armstrong and supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSRHC) − points directly to policy interventions that could arm decision-makers in building a better future for the aging population.

“Decision-makers have a responsibility to ensure nursing home public policy is most consistent with the available evidence and least likely to cause harm,” says Lexchin. “It’s time to re-align policy with evidence. Our seniors deserve better,” he adds.

Nursing homes or long-term care facilities are regulated institutions that provide around-the-clock care for the elderly as well as for those who are unable to live independently due to mental or physical disability.

For-profit institutions have garnered public concerns about the quality of care for senior clients.

Although these institutions can be owned and operated by the government (public), privately owned for profit, or privately owned not-for-profit, the trend in many industrialized countries is private for-profit. This has garnered public concerns about the quality of care for these clients.

Challenges of measuring quality, determining causality

While research in this area is not new – American and British researchers began to look into this in the 1980s – this study is unique. This is because Lexchin and others sought to evaluate the evidence, provided in existing research, for an association between for-profit ownership and inferior quality of care.

“Decision-makers have a responsibility to ensure nursing home public policy is most consistent with the available evidence and least likely to cause harm.” – Joel Lexchin

How does one measure quality of care? There are a number of ways to look at this. Indicators of quality include:

- Structural indicators, such as staffing levels and training;

- Process-based indicators, including inspection violations, continuity of care and prevalence of daily physical restraints; and

- Outcome indicators, such as the prevalence of pressure sores, urinary tract infections and dehydration.

Researchers use causation framework from British epidemiologist

As well as indicators, observational studies can be used to measure the quality of care. In this research, the team used the Bradford Hill’s framework for examining causation – defined as the act of causing something to happen. British epidemiologist, Sir Austin Bradford Hill, developed these guidelines in the mid-1960s to evaluate evidence for a causal effect. Interestingly, Bradford Hill was using the guidelines to address the causal link between tobacco and lung disease.

Quality of care can be determined by indicators such as staffing levels and training, continuity of care, etc.

Bradford Hill proposed that nine relevant factors should be considered before causation can be determined. These factors included:

- Plausibility or the inference of a logical relationship between, for example, characteristics of the sample population in a study.

- Consistency, which refers to things that are observed repeatedly, prospectively and retrospectively, in different populations and situations.

- Temporality, which refers to how things unfold over time and become observable only after a certain lapse of time.

- Experiment, referring to randomized experiments (randomized is a method of assigning people to different treatments in scientific experiments).

Link found between for-profit and reduced quality of care

The team looked at existing research on long-term care facilities with the Bradford Hill lens. For the purpose of this article, four of the nine are showcased:

In terms of plausibility: Research showed that to generate profits, for-profit facilities tend to have lower costs and lower staff-to-patient ratios. Money diverted to shareholders and investors leaves less money to pay for staff, and in turn, having fewer or untrained staff is associated with lower quality.

In terms of consistency: Parallel studies in other sectors found for-profit services to be of inferior quality. (For example, studies looking at the Canadian daycare sector found a similar quality gap between for-profit and nonprofit ownership.) Most American studies, as well as those in other industrialized countries including Canada, Israel and Australia, have reported the association between for-profit status and inferior care.

In terms of temporality: Long-term observational research from the United States and Sweden found that nursing homes converting to for-profit ownership showed a subsequent decline in some quality measures. Conversely, nursing homes converting from for-profit to nonprofit status generally exhibit improvement both before and after conversion.

In terms of experiment: Two studies that the researchers examined looked at newly admitted residents to short- and long-stay facilities, including almost 14,000 US nursing homes. Both found higher rates of hospital admissions and one study demonstrated inferior outcomes for mobility, pain and function measures among residents living in for-profit facilities compared to nonprofit facilities.

The researchers concluded that many of Bradford Hill’s guidelines for causation can be found in published studies supporting a causal link between for-profit ownership and inferior care.

One study demonstrated inferior outcomes for mobility, pain and function measures among residents living in for-profit facilities compared to nonprofit facilities.

“It’s time to re-align policy with evidence. Our seniors deserve better.” – Joel Lexchin

Pushing for policy change

Having proven the causal relationship between for-profit facilities and inferior care, although the relationship is not a simple one, the researchers advocate for change. More specifically, they recommend:

- Selling government savings bonds to raise public funds for capital construction;

- Supporting nonprofit societies with the necessary expertise for them to make competitive bids on requests for proposals; and

- Valuing social capital and links with the community in the bidding process.

They also recommend that all jurisdictions require public funding be earmarked and spent on mandated minimum direct care staffing levels consistent with the evidence, with no possibility for facilities to re-direct this money to other budgetary items (including profit generation).

“At the very least, the precautionary principle should apply to this highly vulnerable population,” says Lexchin. “This shifts the debate by calling for preventive action based on the obvious premise that harms to the public’s health should be avoided and that society should not have to wait for conclusive evidence before acting to protect itself,” he adds.

This SSHRC-funded research was published in PLOS Medicine (2016), under the title “Observational Evidence of For-Profit Delivery and Inferior Nursing Home Care: When Is There Enough Evidence for Policy Change?” To read the article, visit http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001995.

By Megan Mueller, manager, research communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca