A grad student taps into a previously unexplored community in HIV service delivery and programming: the stakeholders. She puts a camera in their hands, literally, and discovers many visual metaphors for the journey of HIV – all of which have compelling implications for practice.

Sarah Switzer, a PhD student (now graduate) supervised by Professor Sarah Flicker in the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change, led a highly original research endeavour as part of her doctoral dissertation: She invited stakeholders within the HIV community to visually document what engagement, in programming and service delivery, meant to them. The results, which have implications for practice, were published in Health & Place (2020).

This project had many contributors including the University of Toronto and Concordia. It was funded by the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research and the REACH 2.0 Canadian Institutes of Health Research CBR (community-based research) collaborative.

Sought to fill an important void in the research

Since the 1980s, when AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) and HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) began to devastate various populations, activists have campaigned for programs and services to support those affected. These trailblazers mobilized public health authorities, governments and the research community, and their actions led to the development of vital programs and services.

Forty years later, HIV research in the social sciences has studied and documented the virus from the perspective of the consumers of the healthcare system, those living with HIV and those impacted by the virus.

Switzer and her team wanted to learn more about stakeholders within HIV community-based organizations and their experiences – specifically, related to engagement, an underexplored area.

What does engagement mean?

Key components of engagement include participation, reciprocity and a personal and organizational investment in the process. “Engagement, a dynamic, relational process, includes a set of participatory practices, and people’s subjective understandings of what it means to actively participate in programs or services,” Switzer explains.

Sometimes community initiatives can fail. Tokenism is a prime example of this, defined in the Cambridge dictionary as pretending to give advantage to those groups in society who are often treated unfairly, in order to give the appearance of fairness.

This calls attention to why this research is critical: HIV transmission often plays out along existing inequalities. Individuals living with HIV often experience heightened forms of marginalization, such as communities of colour, Indigenous communities and/or people who use drugs.

Diverse group of participants from three organizations

The research team secured 36 study participants from three community-based organizations in Toronto, Canada:

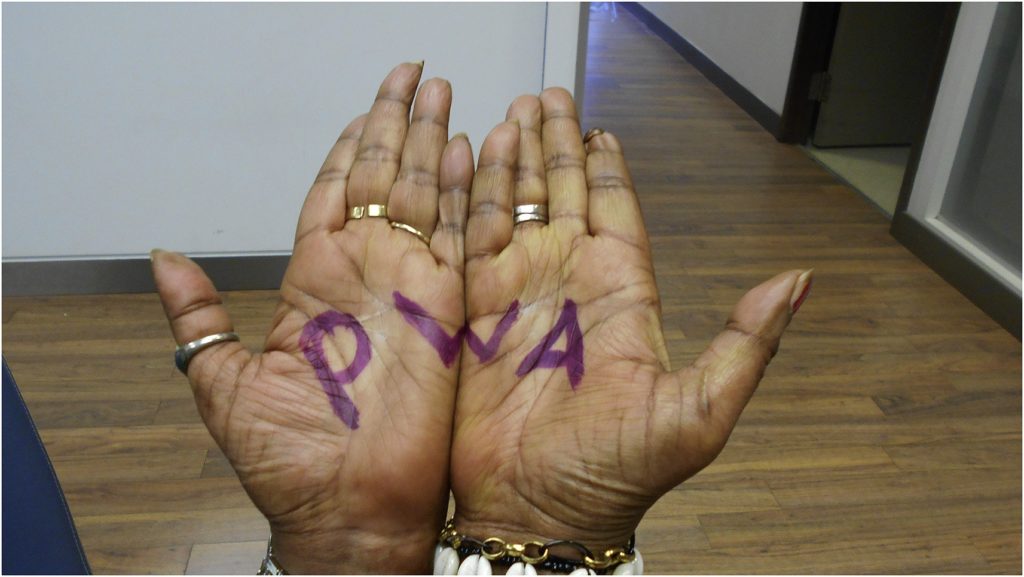

- PWA, Canada's largest service provider for people living with HIV/AIDS;

- Empower, a youth-led HIV prevention and harm reduction program; and

- Casey House, Canada’s first and only stand-alone hospital for people living with HIV/AIDS.

Participants from Empower were former program participants, mentors and a program coordinator; those from PWA were peer volunteers and a coordinator; and those from Casey House were clients and staff.

Through a survey at the start of the project, the researchers learned that the participant group was extremely diverse in terms of age, race, gender, Indigeneity, sexuality, HIV status, disability, role and experience.

Photovoice used to capture experience

Using photovoice, a qualitative research method invented in the 1990s where people take photographs of what they experience, the researchers invited participants to document their understandings of engagement. Participants shared photos and narratives that reflected on seven key themes, including individual and/or organizational journeys.

Over six months, the research team undertook 20 photovoice workshops and 17 photo-elicited interviews. “We introduced the project; brainstormed ideas; provided training on ethics and photography; supplied equipment and instructions for taking photos; discussed, analyzed, and celebrated participants’ work; and created site-specific installations using the images,” Switzer sums up.

Photographs, with narratives, tell a comprehensive story

This work culminated in a curated exhibit of 63 photographs and accompanying narratives that were mounted in several community settings, three installations, a website, co-led workshops and a community report.

The images speak to the themes that emerged, such as reflecting on journey; honouring relationships; accessibility and support mechanisms; diversity and difference; advocacy and peer leadership; navigating grief and loss; and non-participation.

The journey is a foundational concept for this research. “A journey implies a long, sometimes arduous, trek. It evokes notions of change over time, movement, deep learning and attention to process,” Switzer states.

It’s clear that the idea of a journey provided study participants with a way to make sense of their experience. “I love seeing the candle not lit, but there’s times when I like to see the candle lit, because I know that person isn’t suffering anymore,” said one Casey House participant about the image of a memorial candle. Participants also reflected on organizational journeys and how they connected (or not) to individual journeys.

Findings and implications for practice

Essential learnings from the project included:

- Understandings of engagement vary within and across the HIV sector.

- Journey is an apt metaphor to discuss these different understandings.

- Journey metaphors show that engagement is a dynamic and relational process.

- Understandings of engagement are shaped by organizational context(s) and roles.

This work has strong implications for practice. Switzer, Flicker and their team believe that organizations and stakeholders could use the journey lens to pose key questions such as: How did we arrive here? Where do we want to go ― as individuals, as a community, as an organization? How can we go there together? These questions can also unearth important conversations about power dynamics and differentials in community engagement.

Asking these questions could be transformative, the researchers emphasize – for individuals, organizations and the HIV sector as a whole.

To read the article, “Journeying Together: A visual exploration of “engagement” as a journey in HIV programming and service delivery,” visit the journal website. For a copy of the co-authored community report, visit the Picturing Participation website. To learn more about Flicker, see the Faculty profile page. For more on Switzer, see her list of publications.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch; watch our new video, which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity, such as Artificial Intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic, a glimpse of the year’s successes.

By Megan Mueller, senior manager, Research Communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca