Research led by a PhD student in York's clinical psychology program suggests that the benefits of small doses of LSD – such as enhanced mood, creativity, focus and sociability – may overshadow the challenges. While the most commonly reported drawback of microdosing was “none,” clinical studies are still required.

LSD or lysergic acid diethylamide is a mind-altering substance in a class of drugs called hallucinogens. Experiments in the 1950s using LSD showed promise, in terms of psychological benefits, but were shut down due to social and political pressures. By 1966, this drug had become a symbol of counterculture. It was deemed illegal in the United States as a result of its increased recreational use.

But the notion of LSD’s benefits never died in the research community. One intrepid grad student at York University, Rotem Petranker, took up the idea and led an international research team that included academics from University College London (U.K.), the University of Toronto, the University of California, RMIT University (Australia) and the University of Queensland (Australia).

This research, soon to be published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology (accepted), looked into the benefit of microdosing psychedelics – the practice of taking small, sub-hallucinogenic doses of substances like LSD or psilocybin-containing “magic” mushrooms.

It showed that the benefits, such as enhanced mood, creativity, focus and sociability, outweighed the challenges. “Quite remarkably, the most common challenge participants associated with microdosing was 'none,'” Petranker says.

Petranker has already published a great deal in this area. His main research interest is emotion regulation, or the skill of dealing with uncomfortable emotional states in an adaptive way. He is interested in the way emotion regulation interacts with sustained attention, mind wandering and creativity.

Fascinating history of LSD

First synthesized in 1938 by the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, LSD has an intriguing history. Although Hofmann created it as a respiratory and circulatory stimulant, he stumbled upon its trippy effects (no pun intended).

LSD was introduced into the United States in 1949. It was believed that the drug might have clinical applications, re: depression and anxiety. Psychological experiments in the 1950s using LSD were launched to investigate its helpful effect in facilitating psychotherapy, curing alcoholism and enhancing creativity.

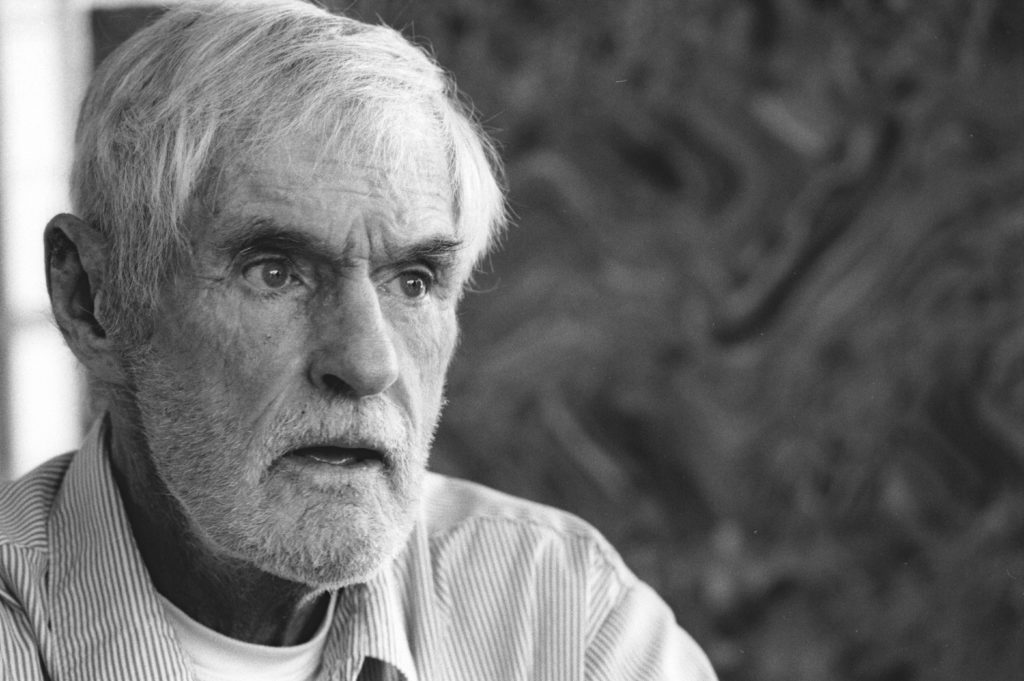

One of the most prominent advocates in the scientific world was Timothy Leary. In the early 1960s, having just arrived at Harvard University, he began to explore the effects of psychotropic substances on the human mind.

The darkest chapter in this drug’s history took place during the Cold War when the CIA allegedly conducted secret experiments with LSD around mind control and psychological torture.

Research fills an important void

Sixty years later, much more research has been undertaken. But Petranker identified a void in this work around the effects of microdosing.

To fill this void, Petranker’s research team sought to replicate the findings of earlier studies on the benefits and challenges of microdosing, and to measure whether people who microdosed tested their substances for purity before consumption. Here, the researchers were interested in whether or not this testing plays a role in or is related to the benefits.

“We hypothesized that an approach-motivation – that is, motivation stemming from approaching a potential reward rather than avoiding a potential harm – would predict more positive outcomes,” he explains.

Researchers dove into the Global Drug Survey with data from over 50 countries

To gain information, the researchers turned to the world’s largest drug survey, the Global Drug Survey (GDS). Using anonymous online research tools, the GDS has access to drug use data from more than 500,000 people in over 50 countries. Here, Petranker found his participants.

For his study, participants who responded to the 2019 survey and who reported the use of LSD (or psilocybin) within the last year were offered the opportunity to answer a specialist sub-section on microdosing. Data from 6,753 people who reported microdosing at least once in the last year were used for analyses.

The researchers asked participants to indicate which benefits, from the following select list, applied to their experience of microdosing:

- Enhanced mood, reduced depression symptoms;

- Enhanced focus;

- Enhanced creativity and/or curiosity;

- Enhanced productivity, motivation or confidence;

- Enhanced energy and/or alertness;

- Enhanced empathy, sociability or communication skills;

- Enhanced sight, smell, hearing, athletic performance or sleep;

- Reduced stress; and

- Reduced anxiety, including social anxiety.

They also asked participants which challenges, from the following select list, applied to their experience of microdosing:

- Negative mood, irritability or instability;

- Reduced focus;

- Legal consequences;

- Restlessness and/or fatigue;

- Social problems;

- Mental confusion, memory problems or racing thoughts;

- Unpredictable effects and/or negative drug interactions;

- Substance dependence symptoms and hard comedown;

- Increased anxiety, including social anxiety; and

- None; I experienced no side effects.

Participants also shared why they chose to microdose. Their reasons included: to enhance creativity; to improve mood and/or overall life satisfaction; to avoid boredom; to escape negative feelings, e.g. depression, anxiety; to get away from bad habits and unhealthy behaviours; and, to treat ADHD symptoms.

Benefits outweigh challenges, minimal side-effects

Most participants, roughly one-third, reported no negative side-effects from microdosing. The most commonly reported positive effects included improved mood and creativity. Focus and sociability improved for some.

This research also showed that participants did not test for purity before taking the drug, leading the researchers to determine that the perceived benefits associated with microdosing greatly outweigh the potential risks.

“Microdosing may have utility for a variety of uses while having minimal side-effects,” Petranker concludes.

He presses, however, for more research. “Double-blind, placebo-controlled experiments are still required to substantiate these reports,” he states.

To read the article on microdosing psychedelics in the Journal of Psychopharmacology visit the website. To learn more about Petranker’s work, visit the Toronto Centre for Psychedelic Science website.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch; watch our new video, which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity, such as Artificial Intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic, a glimpse of the year’s successes.

By Megan Mueller, senior manager, Research Communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca