A grad student analyses antimicrobial resistance and finds some countries handle it better than others. Success is based on disassociating from profit-minded pharmaceutical companies and political agendas – a noteworthy finding for public and global health policy-makers.

Antimicrobials are medicines, such as antibiotics, used to prevent and treat infections in humans, animals and plants. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) happens when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines. This makes infections much harder to treat which, in turn increases the risk of disease spread, severe illness and even death.

AMR is an urgent threat to public health and, in fact, one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Faculty of Health grad student Ilinca Dutescu sought to address this threat head on; she wanted to tackle this complex societal challenge. She authored a new article on AMR, published in International Journal of Health Services (2020), in which she focuses on the underlying causes of inappropriate behaviours related to antimicrobial use – namely, political agendas and the best interests of powerful elites.

“To avoid returning to a society in which common infections once again become deadly, we need to consider the often-ignored root causes driving inappropriate behaviors relating to antimicrobial use, such as the history of antimicrobial drug development by big pharma, the effects of commodifying health-related services, and the rise in social inequalities,” she says.

Interestingly, Dutescu, now a research coordinator at St. Michael’s Hospital, set out to write this paper to fulfill the requirements of Faculty of Health’s Professor Dennis Raphael’s graduate-level class. With Raphael's feedback, she edited the work to render it suitable for publication.

Raphael’s area of expertise is the social determinants of health – that is, the socio-economic conditions that shape the health of individuals and communities. These conditions, primarily a deepening class and income inequity, determine an individual’s access (or lack of access) to vital resources.

Chiefly aimed at informing policy, this perspective critically analyzes the inequities embedded in our society and the socio-economic factors that affect health, including income, education, employment, housing, food security, gender and race.

AMR comes with high costs and high risks

The cost of AMR to the economy is not insignificant. This includes death, disability, prolonged illness, longer hospital stays, the need for more costly medicines and financial challenges for those impacted by AMR.

The risk is also high: Without effective antimicrobials, the success of today’s medicine in treating infections, including during major surgery and cancer chemotherapy, would be at increased risk.

“Despite large investments being allocated to this, the incidence of untreatable, antimicrobial-resistant diseases continues to rise in many nations,” Dutescu emphasizes.

Study looks at role of powerful elites in setting agenda

Dutescu looks at the problem in a wholly unique way that highlights the influence that powerful organizations have in steering national policymaking. Her political economy approach analyzes why certain groups or societies have better health outcomes than others. (Political economy is a branch of the social sciences that focuses on the interrelationships among individuals, governments and public policy.)

“Under this lens, policymaking and action in response to public health threats are seen as being dependent on pre-defined political agendas and the best interests of powerful elites,” she explains.

Focus on successful Nordic model

Dutescu’s research includes a fulsome analysis of how AMR has been handled in Europe and North America. She considers national differences in pharmaceutical industries’ profit-driven tactics; and the successful Nordic model.

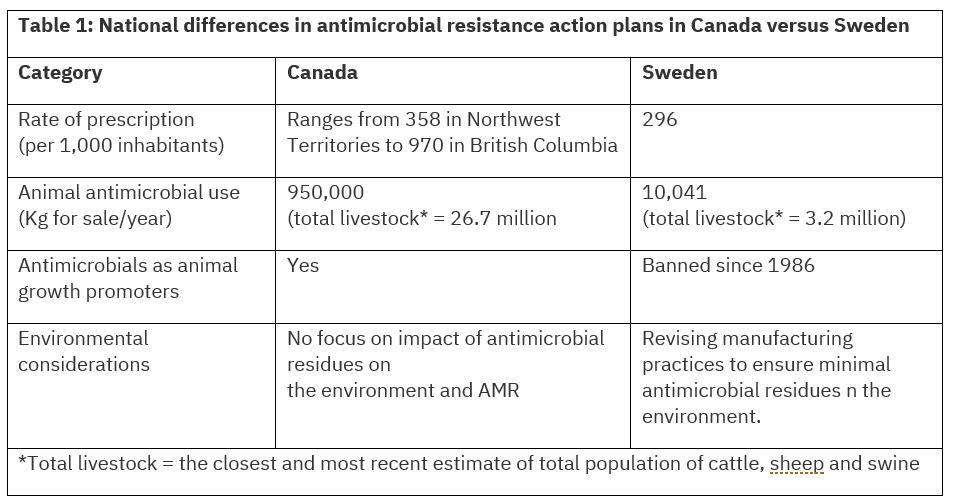

Table 1 compares the action plans aimed at solving AMR in Canada, a liberal welfare state, versus Sweden, a social democratic welfare state. In Sweden, for example, the use of antimicrobials as animal growth promoters has been banned since 1986, while antimicrobials continue to be used for this purpose in Canada.

“Canada demonstrates fewer antimicrobial regulations – especially regarding antimicrobial use in animals – which may have contributed to the rise in AMR in Canada compared to Sweden,” Dutescu sums up.

What’s at the heart of the differences between these two countries?

Simply put, in Sweden, the central goal was “to prioritize human health by limiting the production of drugs that did not provide a new benefit to the public, rather than to maximize profit,” Dutescu explains.

“Social democratic countries, such as Scandinavian countries, tend to not simply see drugs as commodities, but rather as therapeutic agents for public health. This perspective has allowed them to develop antibiotics sustainably, thereby benefiting their entire nations, rather than only benefiting the pharmaceutical industry and those with vested interests in it,” she elaborates.

As a result, Nordic countries have the lowest worldwide rates of AMR and antimicrobial use. “This observation suggests that AMR is discouraged when pharmaceutical companies are bound by regulations that limit profit through strict policies pertaining to the approval and use of new antimicrobials,” Dutescu emphasizes.

By contrast, in Canada and the United States, AMR rates and antimicrobial usage are substantially higher. Dutescu points to strong market influences that characterize liberal welfare regimes: “The long-term health of citizens takes second stage as profit-driven pharmaceutical industries are left to pursue their self-interest with minimal state intervention.”

Health promotion strategies and new policies that recognize powerful forces at play

Dutescu believes that the solution lies in health promotion strategies that recognize the powerful economic and political forces at play in many nations – that is, the profit-driven pharmaceutical companies operating without governmental regulation.

She believes that new policies are needed to enforce targeted regulations pertaining to antimicrobial use in production animals, among other things.

These actions would need to be coupled with appropriate stewardship programs, led by public institutions, to prevent against antibiotic misuse, thus maximizing the benefits for the public and minimizing collective harm.

To read the journal article, visit the website. To learn more about Raphael, visit his faculty profile page.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch; watch our new animated video, which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity, such as Artificial Intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic, a glimpse of the year’s successes.

By Megan Mueller, senior manager, Research Communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca