Lorne Foster

York Professors, hired to examine racial profiling, determine that police stop racialized minorities at a disproportionate rate, and propose evidence-based policy recommendations.

York University is known for leading scholarship in equity and human rights. Its researchers are nationally recognized for their policy-relevant contributions. As two of Canada’s foremost equity scholars, Professors Lorne Foster (Department of Equity Studies) and Les Jacobs (Department of Social Science) were hired by Ottawa Police Services to examine traffic stops along racial lines.

The Ottawa Police turned to Foster and Jacobs because they bring “a combination of research experience and knowledge on the issues of race and ethnic relations, human rights, data collection, empirical research, social justice and public policy,” said the Ottawa Police statement.

Les Jacobs

Foster and Jacob’s research (2013-2015) determined that Middle Eastern and black drivers, particularly young men, were being stopped at a disproportionate rate. While emphasizing that the study was intended to inform future studies, not to prove racial profiling, Foster and Jacobs provide recommendations that will be of great value to policy-makers across Canada.

“This pioneering research project constitutes the largest and most comprehensive race data collection in Canadian policing history,” says Foster, cross-appointed to the School of Public Policy and Administration. “The findings enable evidence-based policy- and decision-making with regard to bias-free policing,” he adds.

Racial profiling, and how to combat this form of institutionalized racism, are of paramount interest within and outside of academia, including civil and human rights groups, politicians and members of the public.

Racial profiling is defined by the Ontario Human Rights Commission as “Any action undertaken for reasons of safety, security or public protection, that relies on stereotypes about race, colour, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, or place of origin, or a combination of these, rather than on a reasonable suspicion, to single out an individual for greater scrutiny or different treatment.”

Chad Aiken’s case spurred the Traffic Stop Race Data Collection Project. Photo reproduced with permission of CBC.

This research study, the Traffic Stop Race Data Collection Project, which Foster and Jacobs undertook with adjunct Professor Bobby Sui, was spurred by a particular case in 2005: 18-year-old Chad Aiken, a young black man who was pulled over while driving his mother’s luxury car in Ottawa. Aiken, who filed a human rights complaint against Ottawa police, said that he was punched in the chest by the police.

Data collected from 80,000+ traffic stops

The researchers reviewed data from 81,902 traffic stops of Ottawa residents by the Ottawa Police Force between June 27, 2013 and June 26, 2015. They examined the relationship between race, sex, age and traffic stops. Officers were asked about the driver’s race, gender, age, the reason for the stop and if the stop resulted in charged.

The researchers looked at the data in three different ways: incidences, reasons and outcomes.

Analysis A: Data by incidences of traffic stops

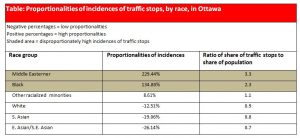

The data showed that the Ottawa police stopped Middle Eastern drivers over 10,000 times, which represented over 12 per cent of the stops. (See table.) These drivers represent less than 4 per cent of the general population, which means that they were stopped 3.3 times more than what you would expect based on the population.

Similarly, black drivers were stopped over 7,000 times or 8.8 per cent of the time, which was about 2.3 times more than you would expect based on the population of Ottawa. (See table.)

The disparities were even more pronounced when the researchers looked at the drivers’ age: Middle Eastern men, ages 16 to 24, were 12 times more likely to be stopped; while black men, 16 to 24, were over eight times more likely to be stopped.

Analysis B: Data by reasons for traffic stops

The data also showed that 2,299 cases involved “suspicious activities,” and in this category, a disproportionate number were racialized minorities.

However, the vast majority of traffic stops (97 per cent) were for municipal and provincial offences, such as not wearing a seatbelt, and no particular group was disproportionately stopped.

Analysis C: Data by outcomes of traffic stops

Outcomes of traffic stops can be no action, warned or charged. Forty-four per cent of stops ended in charges, while 41 per cent ended in a warning – and in these cases, race did not play a part.

However, black and Middle Eastern drivers were more likely to have a “no action” outcome. So these groups are being stopped more readily by Ottawa police, but not being charged or being given a warning.

This research showed that Middle Eastern and black drivers, particularly young men, were being stopped at a disproportionate rate.

Recommendations geared towards bias-free policing

The report, submitted to the Ottawa Police Services Board and the Ottawa Police Services in October 2016, makes six recommendations:

- Through examining the psychological, organizational and social issues within the Ottawa Police, determine the sources for the disproportionate traffic stops. This will involve looking at systemic biases in police practices, police leadership and corporate culture, etc.

- Develop and implement solutions to address the situation in consultation with stakeholder groups, race and ethnic communities and the public.

- Increase positive police-community contact through regular, relationship-building meetings; training officers and community members together; holding ‘critical incident’ discussions; etc.

- Continue monitoring race data in traffic stops, and regularly communicate this to the public through quarterly bulletins, press releases, etc.

- Build on community engagement and develop an action plan to address the issues raised in the report.

- Within legal limitations, make the data in this research readily available to facilitate future studies.

Ottawa Police Chief Charles Bordeleau. Reproduced with permission of the Ottawa Police.

“We have received the report, and we are committed to working with the community and our members to develop an action plan,” said Ottawa Police Chief Charles Bordeleau in a press release issued after the report was released by the York University researchers.

Foster and Jacobs are optimistic. “The very undertaking of a racial profiling study is essentially a reaffirmation of this multicultural community value,” says Jacobs, cross-appointed to the Department of Political Science. “Such a process promises to promote effective bias-neutral policing and strengthen community-police relations.”

For more information, the full report is available at http://bit.ly/2ijAdAr. A shorter executive summary of the report is available at http://bit.ly/2hveBkt. To see slides presented by the report authors, visit http://bit.ly/2hgu6kx.

By Megan Mueller, manager, research communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca